All along the watchtowerby Dwayne A. Day

|

| MOL’s story has never been fully told, and what has been told has sometimes been inaccurate and certainly woefully incomplete. |

For its first year and a half MOL apparently existed in a kind of bureaucratic limbo. It was approved by the Department of Defense, but this was insufficient to move the program forward very far, something that is difficult to understand given available records. In August 1965 President Lyndon Johnson signed a directive approving MOL. This probably resulted from a change in the nature of the program, most likely an expression of much-needed support from the intelligence community.

By 1965 the program was faltering. Its proponents had quickly fallen into a classic Catch 22: the Air Force had to prove that military astronauts were useful before they could put them in space, but they had to fly them in order to figure out that they could do something useful. And that’s when a major change occurred in the program, something that most people researching MOL have failed to note, or even been aware of: MOL pre-1965 was apparently significantly different than MOL afterwards, but the vast majority of available records on MOL concern the early version of the project, not what the Air Force ultimately decided to fly.

To truly understand the change, it is necessary to know something about the arcane world of the military space bureaucracy. The Air Force had its own “blue-suit” space program run by the Space Systems Division and based in Los Angeles. But there were also Air Force officers who worked for a super-secret “black” Department of Defense agency called the National Reconnaissance Office. The two groups occasionally interacted, but were largely segregated, and there were blue-suiters in the Air Force space program who were completely unaware of the highly classified intelligence spacecraft that were being developed by their fellow officers who often worked down the hall in the same facilities.

Around 1965 or 1966 MOL acquired a major new sponsor, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), and a massive telescope, which the NRO designated the KH-10 DORIAN. According to one person who saw a top secret illustration of MOL after the program was canceled, the final configuration looked a lot like the Hubble Space Telescope with a downward-pointing telescope nested in a long unpressurized tube and a pressurized cylinder atop it, crowned with a Gemini spacecraft pointing out toward the sky. MOL’s primary mirror was the largest space-based mirror ever produced up to that time—183 centimeters (72 inches) in diameter. Instead of a largely experimental mission with lots of little experiments, the MOL astronauts would fly an operational mission, spending most of their time pointing the DORIAN camera at ground targets and taking high-resolution photographs.

There were a lot of skeptics about this plan. MOL was proceeding slowly throughout the 1960s at a time when robotic spacecraft were advancing rapidly, their lifetimes and capabilities increasing substantially in the mid-1960s. MOL had also been designed from early on to operate unmanned, raising questions as to why the humans were even necessary. MOL cost a lot of money that many in the Air Force believed should be spent on Vietnam, by then a very high-tech war.

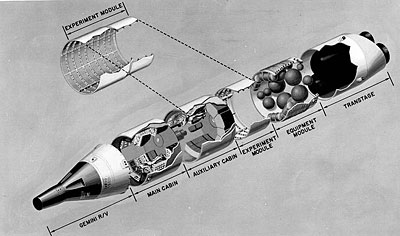

MOL had several major development components. Although the Gemini B spacecraft (not to be confused with the earlier Blue Gemini proposal) could be purchased virtually off the shelf—albeit with a hole cut in its reentry shield for an access hatch to the main spacecraft—the MOL laboratory was new and complex. The Titan III rocket was also a major expense, as was its new launch facility. The government used eminent domain to seize the large Sudden Ranch to the south of Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, and began building a massive launch complex there. Eventually the MOL program included seven development flights between 1968 and 1971, and at least six operational flights starting in 1971, although details remain classified.

There were nuisances to overcome as well. A Florida senator objected to launching MOL out of California when there was already a perfectly good launch facility in his own state. This required Department of Defense officials testifying before Congress to deftly deflect attention from the fact that they needed to launch from California in order to spy on the Soviet Union.

| As one former senior Air Force official once put it, the program always seemed to be one year and one billion dollars more away from completion. |

MOL was an expensive project, and by 1967 it was clashing with another space project, a massive robotic spacecraft designated the KH-9 HEXAGON. Whereas MOL was primarily an Air Force program with NRO involvement, HEXAGON was the reverse, an NRO program—largely managed by the CIA—with the Air Force providing some major parts, particularly the Titan III launch vehicle, which was also being modified to carry humans on the MOL. The cameras for the two spacecraft were different and intended to do different things. The DORIAN camera was very high resolution and could only see small parts of the Earth. A human hand would operate the shutter, focusing on “targets of opportunity.” One person responsible for training the astronauts how to recognize such targets remembers showing them a satellite photograph of a Soviet submarine that had been pulled out of the water. The sub’s propeller blades were clearly visible—and countable—something that was extremely rare for satellite photographs that normally only captured more mundane scenes. The HEXAGON camera had lower resolution, but could photograph massive amounts of territory underneath, scanning vast swaths of the Soviet Union looking for changes.

The four-inch question

But the Air Force was stuck with paying the bills on two new expensive satellite projects and in 1968 this forced one of several showdowns. Vice President Hubert Humphrey held a briefing where MOL’s advocates were asked to make their case. Humphrey was accompanied by Director of Central Intelligence Richard Helms, whose own agency was firmly committed to building the HEXAGON.

According to one person who was present, Helms remained silent throughout the meeting while Humphrey was briefed on both the HEXAGON and the MOL. But near the end of the MOL briefing Helms wrote something on a piece of paper and slid it over to Humphrey, who looked at it but did not say anything. After the meeting was over, this person hung around the room until everybody left and then picked up the piece of paper. On it, Helms had written a short question: “Why four inches?”

Four inches (10 centimeters) happened to be the resolution of the MOL’s DORIAN camera, and it was also a source of contention between the CIA and the Air Force. The CIA had conducted many studies of what trained human eyeballs could see in overhead (i.e. satellite and aerial) photography. They had determined at what resolution a human could distinguish a tank from an armored personnel vehicle, and at what (better) resolution a human could tell one kind of tank from another. Although there was a natural drive towards better and better resolution, higher resolution came with other costs, primarily a smaller viewing area—think of the difference between looking for an airplane in the sky using a telescope versus a pair of binoculars. The CIA had concluded that MOL’s four-inch resolution was excessive, unnecessary, and damned expensive.

MOL did not die that day, but the program was already in serious trouble. As one former senior Air Force official once put it, the program always seemed to be one year and one billion dollars more away from completion. When MOL was finally canceled in summer 1969, a lot of people were apparently stunned by the decision, and many of them lost their jobs. One senior MOL manager was at that very moment testifying in a closed meeting in Congress about MOL’s capabilities when he was handed a note saying that President Nixon had killed it. He was shocked, and so were the members of Congress.

By the time it was canceled, the Air Force had spent $1.4 billion on MOL development and had ramped up to annual expenditures of nearly $500 million. To understand the magnitude of this expenditure, consider that roughly adjusted for inflation, today that is over $8.5 billion in development funding and $3 billion in annual expenditures.

| Although amateur historians—and apparently the Nova program—focus on the military astronauts, many of whom went on to later NASA careers, a lot of big questions about MOL remain unanswered. |

Much of the shock over MOL’s cancellation can probably be attributed to the security compartmentation of the program. Although it seems likely that nearly everybody working on the MOL was aware that it was carrying a top secret piece of equipment, probably very few were aware that at least two highly classified studies of that equipment indicated that it was unlikely to work. The studies had concluded that putting humans alongside a powerful optical instrument dramatically undercut its capabilities. Humans bumped things, they had to exercise, and they required air that had to be moved around with fans. All this meant vibration, and vibration is bad for finely-tuned optics that have to be precisely pointed at targets hundreds of kilometers away. Worse, their spacecraft would outgas, and they would have to dump urine overboard, where it would interfere with the optics system. NASA discovered this phenomenon in the 1980s, when the Space Shuttle proved to be a very dirty platform from which to conduct observations. As one person noted years later, MOL had been living on borrowed time for several years before its “sudden” cancellation.

Although many in the Air Force were crushed by MOL’s cancellation, and it spelled the beginning of the end of the Air Force’s fascination with military man in space, others soon found the cancellation to be a windfall. MOL was sucking up a lot of money in the Air Force’s research and development budget, and suddenly dozens of other projects that had been struggling for funding, like precision-guided bombs for Vietnam, received a big influx of money.

Watchtower still hidden in the shadows

Today relatively little is known about the MOL program other than its overall outlines. Although amateur historians—and apparently the Nova program—focus on the military astronauts, many of whom went on to later NASA careers, a lot of big questions about MOL remain unanswered. What was its real purpose? Who established its requirements? What was its schedule and how many MOLs did the Air Force plan to build? What was the story behind its delays and cost overruns? Who were its proponents and its opponents? Why did the NRO leadership agree to become involved in a human spaceflight program after apparently deciding in the early 1960s that they wanted no part of human spaceflight? And how were responsibilities divided between the Air Force and the National Reconnaissance Office bureaucracy? Did the CIA openly fight MOL?

Also unknown are many technical questions. Did the Air Force recognize the requirement for astronaut exercise for long-duration spaceflight and how did they accommodate it? How would the astronauts coordinate their eating, sleeping, maintenance, and exercise schedules with the need to peer through the telescope every time they flew over the Soviet Union? What did MOL actually look like on the inside? How did it obtain power and point itself? What kinds of equipment would it carry and how? And how would it return its film back to the ground—via the cramped Gemini or, more likely, with ejectable reentry vehicles? And how much actual test and flight hardware was actually built and what happened to it all? Those questions cannot be answered as long as the program remains classified.

MOL’s launch site at Vandenberg was completed with some additional funds after the cancellation of the program, and then placed in mothballs. Eventually the launch site was converted for the Space Shuttle, but then shut down and mothballed again in the 1980s. Only recently has it been pressed into service for what it was originally intended, launching big rockets. The Titan III, of course, was used to launch numerous other payloads into space, but it was already underway by the 1960s and it is difficult to determine how much credit to give the MOL program for improving the Titan III.

It also appears that, rumors to the contrary, much of MOL’s technology was never incorporated into follow-on programs. Several big mirrors for MOL’s DORIAN telescope were manufactured, but they were eventually donated to the University of Arizona’s Multi-Mirror Telescope Observatory. One former industry official recounted how he was told to pitch a camera developed for MOL to NASA’s Skylab program, something for which it was terribly unsuited. A few minutes into the meeting he halted the pitch and told the surprised, and grateful, NASA official that they were wasting his time, infuriating the man’s boss and convincing both of them that the man did not really belong in industry if he was not willing to try to sell products to people who did not want them. One of the ironies (or hypocrisies) of the whole event was that only a few years after MOL’s cancellation the CIA began working on a satellite known as the KH-11 KENNAN which used a 240-centimeter (94.5-inch) mirror to provide 7.5-centimeter (3-inch) ground resolution, something that the agency had claimed was unnecessary when the Air Force wanted to do it.

| Why the NRO refuses to even acknowledge MOL at a time when it at least vaguely acknowledges involvement in programs that followed it, like the KH-11, remains unknown. |

Thousands of documents on MOL’s early years have been declassified, although little-used by historians. They only cover the years before the MOL took a sudden new direction, leaving essentially half of MOL’s history concealed in darkness. An official history of the program remains highly classified. In response to a Freedom of Information Act request, the NRO adopted the “Glomar response” (named after the CIA’s Glomar Explorer ship used to recover portions of a Soviet submarine) refusing to acknowledge that it may have records indicating an association with the MOL, even though there is significant declassified documentation demonstrating that MOL was intended to conduct NRO missions. Why the NRO refuses to even acknowledge MOL at a time when it at least vaguely acknowledges involvement in programs that followed it, like the KH-11, remains unknown. However, American secrecy policy encompasses many decisions that appear inexplicable and contradictory to outsiders, and probably little better to those who actually know why they were made.

Hopefully, the Nova documentary can shed some new light on these issues, but given the secrecy cloak that has been thrown over the program, there are good reasons to be skeptical.