Unilateral orbital cleanupby Taylor Dinerman

|

| When it comes to actually doing something about the problem the task and most of the cost will almost inevitably fall to the Americans. |

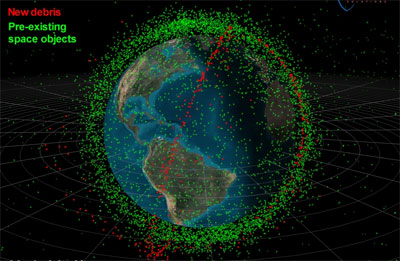

Over the years there have been many ideas floating around on how to deal with this problem. While international agreements, such as the 2007 Debris Mitigation Guidelines or proposals to share space situational awareness information, may be marginally useful, they will never, by themselves, remove a single speck of space junk from our planet’s neighborhood. When it comes to actually doing something about the problem the task and most of the cost will almost inevitably fall to the Americans.

Nick Johnson, NASA’s top expert on space debris, has stated, “This is a big environment and the US doing something by itself is not sufficient.” However, if the Americans do nothing then it’s likely no one else will either. It sometimes seems as if those in power in Washington and elsewhere are more interested in making excuses and explaining why they cannot actually do anything about the problem than they are in trying to figure out an effective response.

This raises the question of what would actually work? High-powered lasers, like those developed for the Airborne Laser (ABL) missile defense system recently cut back by Defense Secretary Robert Gates, might be useful dealing with a limited amount of debris in very low Earth orbit. It would certainly be worthwhile testing this idea instead of dismissing it out of hand. The big problem, however, is well beyond the range of any existing laser.

What is required is a new type of space maneuver vehicle, one that can rendezvous with, catch, and store a bit of debris, and then proceed to the next one. Such a vehicle would not need to move very fast: the process would be a leisurely one, and thus would allow for the use of a highly efficient space propulsion system such as a pulse plasma thruster or ion engine. Each move could be as carefully planned as the moves of the Mars rovers are. The operations could be carried out according to a plan that would deal with the most dangerous pieces of debris first.

Designing and building these spacecraft would involve a virtuous technology cycle: a steady process of marginal improvements, somewhat akin to what we have seen with the GPS satellites. Each advance in the subsystems would be integrated into a new block of satellites The design and manufacturing teams involved will constantly be sharpening their skills. Again, as with GPS, the companies building these spacecraft will have to compete for the contracts and will thus have to pay careful attention to the quality and cost of their work.

As with GPS cleaning up Earth orbit is a job best left to the US Department of Defense. It may legitimately be argued that the Pentagon already has too much to do and that the last thing it needs is to take on yet another task, especially one that involves providing the international community with another “global good”. However, in the broad scheme of things it would be better for the US military to provide this essential service than to leave it to NASA or to a nebulous international consortium.

| An international consortium is a recipe for doing almost nothing and doing it very, very slowly. Certainly the Pentagon’s procurement process leaves much to be desired—and that’s putting it mildly—but it is far better than the alternatives. |

By the end of the next decade, NASA, if all goes well, will be getting out of the business of operating spacecraft in Earth orbit. The ISS may still be useful but one hopes that by then the Earth sciences mission will have been handed over to NOAA and to the National Science Foundation. In any case the agency has its hands full trying to accomplish the exploration goals that the President and Congress have already agreed on.

An international consortium is a recipe for doing almost nothing and doing it very, very slowly. The process of negotiating the preliminary agreement would probably take more time than it took the Defense Department to go from concept to the first GPS satellite in orbit. Figuring out the industrial politics of a multinational debris collection spacecraft manufacturing project would add years to the whole program. Certainly the Pentagon’s procurement process leaves much to be desired—and that’s putting it mildly—but it is far better than the alternatives.

Of course the expertise the US would develop while performing this task would have many useful military applications, and as such would be objected to by those who are always on the look out for anything that looks like a US “space weapon”. Such spacecraft, though, would move far too slowly to themselves be used in an effective anti-satellite mode. The skills involve would in fact be far more useful in the robotic building of large structures in space, including solar power satellites.

Eventually other nations would see America gaining prestige and technological advantages from its efforts and would try and emulate it. Such emulation would only show that Washington had the right, public-spirited idea in the first place. It would be far better for President Obama’s administration to begin the process of developing the spacecraft that will clean up Earth’s celestial neighborhood now, rather than to wait for an international consensus or for more incidents to happen.