Space war and Futurehype revisitedby Nader Elhefnawy

|

| Sterling characterized the United States as already the planet’s “astrocop,” patrolling an orbital beat and enforcing “world peace, Washington-style”. |

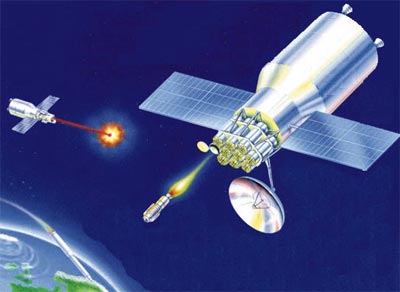

The dialogue on space warfare during the 1990s and early 2000s reflected such thinking, and as a result frequently looked like an inversion of Peter N. James’s famous warning about “Soviet conquest from space”—American space dominance (see “Space war and Futurehype”, The Space Review, October 22, 2007). The US Space Command’s February 1997 Joint Vision 2020 document, widely seen as a starting point for such thinking, called for the US to plan for “space defense and even space warfare,” extending beyond the development of “ballistic missile defenses using space systems” and the protection of American space assets through “robust negation systems” to the exercise of “control of space,” including the denial of the use of space to other actors. It also called for “the application of precision force from, to, and through space,” including “precision strike from space” with “Space-Based Earth Strike Weapons” adequate to supplant traditional air, land and sea forces in some missions during this time frame.

Grandiose as all this sounds, the picture painted by JV 2020 is a modest one next to the visions propounded by military theorists like Ralph Peters. In the concluding chapter of his book Fighting for the Future: Will America Triumph? (1999) he depicts a future in which the United States enjoys complete, continuous and global battlespace dominance through a vast array of

attack systems deployed in near space that can, on order, destroy the vehicles, aircraft, missiles, and ships of any aggressor anywhere on the planet the moment a hostile actor violates or even threatens the territory of another state or entity—or uses military means to disrupt the internal rule of law in his own state… The least hostile military action would bring down a rain of fire from the heavens, destroying an attacker’s military inventory, whether he has deployed it, hidden it, or simply left it behind in garrison.

With American dominance so complete, other militaries would be rendered so useless that they would wither away for only “constabularies and police forces need remain” apart from the aforementioned forces of the US and “a few morally coincident allies, such as the other English-speaking, law-cherishing states.”

Such schemes did not remain wholly the purview of defense planners and military theorists. A nearer-term, less technologically radical version of this vision was the cover story of the April 2002 edition of Wired magazine, in which Bruce Sterling presented such dominance as a foregone conclusion. He characterized the United States as already the planet’s “astrocop,” patrolling an orbital beat and enforcing “world peace, Washington-style,” a pattern established by the 1991 Gulf War, the 1999 air campaign against Yugoslavia, and the 2001 overthrow of the Taliban. Sterling, who dubbed these conflicts Space Wars I, II and III, argued that these operations successively demonstrated an increasing American lead in military capability, creating a situation in which there would still be the well-known tactics of terrorist groups at the low-intensity end of conflict, and the threat of weapons of mass destruction at the high end, but

no war as war is usually understood. No Sommes, Verduns, or Iwo Jimas, probably not even any Vietnams or Afghanistans. Just Space War IV, V, VI, until everyone gets it, the last stiff-necked mountain tribe, the last hermit kingdom.

In the 2003 issue of the US Army War College Quarterly Parameters, I argued that such visions were simplistic on the grounds that the hugely expensive capabilities in question could and would be countered, neutralized, and subverted by other powers in various ways besides terrorism and WMDs. With the passage of almost a decade since I penned that article, both the strategizing about “astrocop,” and my criticisms of it, seem awfully dated for a number of reasons, two of which seem to me worth discussing here.

The first is a wider and deeper recognition of the infeasibility of the systems involved, a point demonstrated by Nancy Gallagher and John Steinbrunner’s study Reconsidering the Rules for Space Security. The high cost of space launch, the inflexibility and vulnerability of space systems, the limited number of orbital slots, the limits of sensor performance, the vast numbers of systems required to fully monitor the Earth’s surface and orbital space, and the problems of managing (downloading, storing, and analyzing) the vast amount of information such an enlargement of capabilities would involve make anything like comprehensive global coverage by reconnaissance systems, let alone weapons systems, unattainable not only with today’s technology, but also with such technology as is likely to come out of present R&D efforts.

| The gap between the wealth and technology needed to realize the kind of space dominance imagined by the authors of JV 2020, Ralph Peters, and others, and the wealth and technology actually at our disposal, seems far wider than the optimists guessed they would be in 2011. |

The second reason is a wider recognition of America’s changing economic position, which has for the most part validated the warnings of ’80s-era declinists. After the bursting of the housing bubble, the resurgence of commodity prices, and the financial crisis into which they have fed, it has become far harder to ignore the fact that the problems which got so much attention twenty years ago and so little since have not only persisted, but worsened significantly. The US trade deficit exploded during the last decade, running at the level of five to six percent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product until the global economic crunch depressed consumption—a reflection not just of the US living beyond its means, but also its decline as a manufacturing power and its inefficient use of energy, particularly oil-derived energy. The Federal debt hit 100 percent of GDP this year, a level not seen since the aftermath of World War II, and is now financed by unprecedented foreign borrowing. Meanwhile, the neglect of the country’s transport, communications and utilities infrastructure has run the bill for a five-year overhaul up to $2 trillion.

As US trade deficits feed global financial instability, the dollar weakens internationally, American bridges crack, and the country’s long-slipping standard of living now declines so unambiguously that the matter has become a headline, it is also more difficult to pretend these problems do not matter (see “Space and the end of the future”, The Space Review, March 12, 2007). Indeed, it is clearer than ever before that the economic policies that prevailed during the past few decades were a “winning” strategy only in Charlie Sheen’s sense of the term, and that there is no assurance that this trajectory will end with the kind of soft landing pampered celebrities frequently enjoy after bouts of self-destructive behavior. Instead the stresses, the losses, and the bills seem likely to keep mounting, with an aging population and a global resource crunch almost certain to impose significant costs and constraints above those already mentioned in the decades ahead. And while virtually every country in the world will have to deal with those same issues, the combination of America’s position and problems suggest the post-World War II trend of a shrinking American share of the world economy (which has persisted even as particular challenges, like the Soviet Union, have waxed and waned) will only continue, with predictable consequences for its military lead over the rest of the world.

In short, the gap between the wealth and technology needed to realize the kind of space dominance imagined by the authors of JV 2020, Ralph Peters, and others, and the wealth and technology actually at our disposal, seems far wider than the optimists guessed they would be in 2011. (In the chapter quoted above, Peters imagined the US footing the bill for its ambitious space forces through the continuation of the “revolution of technological and informational wealth creation” it was experiencing in the 1990s—essentially, the tech boom’s lasting for a very long time.) The gap also seems likely to get bigger rather than smaller for the foreseeable future. This makes the extravagant strategic concepts of the 1990s and after just another example of the long tradition of projects belonging to what Dwayne Day has memorably termed the “rhetorical military space program”, which tend not to “abide by the laws of physics… the laws of bureaucratic and international affairs… [or] the laws of fiscal reality.” (See “General Power vs. Chicken Little”, The Space Review, May 23, 2005) Especially with the US defense budget now being cut, reducing the funding for forces of all kinds; with such threats as do exist to the American use of space likely to be successfully met only by more conventional means, military and non-military; and the greatest threats to American security in the coming years much more likely to lie in the realms of the economic and the ecological than in foreign armies, navies, and air forces, terrestrial or space-based; it seems long past time to set aside the astrocop proposals.