Regulating the void: In-orbit collisions and space debrisby Timothy G. Nelson

|

| There remains significant scope for debate over who if, anyone, is liable for in-orbit collisions from “space debris.” |

Many collisions occur within space itself. A recent example was the January 2009 collision, in Low Earth Orbit above Siberia, of the “defunct” Russian satellite Kosmos 2251 with Iridium 33, a privately-owned US satellite. The crash occurred at a relative velocity of 10 kilometers/second, destroyed both satellites and reportedly created a very large field of new debris. As discussed below, there remains significant scope for debate over who if, anyone, is liable for in-orbit collisions from “space debris.”

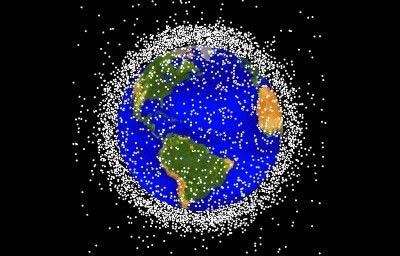

I. The phenomenon of space debris

Space debris, or space junk, is a shorthand reference for any man-made objects lingering in space, as a (sometimes inevitable) byproduct of space activities. Science fiction writers sometimes liken space flight to seafaring; however, the analogy is flawed: ships wrecked on the high seas typically sink, with no long-term impact on other surface traffic. Aviation is likewise a false analogy; debris from aircraft does not linger in the atmosphere but instead falls to earth. In space, by contrast, as a simple matter of Newtonian physics, particles in a weightless environment will continue on their current trajectories indefinitely, unless or until they collide with other particles, just as the defunct Kosmos 2251 satellite collided with Iridium. Moreover, due to the kinetic force of high-velocity objects, even a tiny particle can cause enormous damage. “A 0.5 mm paint chip travelling at 35,000 km/hr (10 km/sec) could puncture a standard space suit.” A one-centimeter fragment can damage a space station.

| There remains significant scope for debate over who if, anyone, is liable for in-orbit collisions from space debris. |

Of course, the remnants of these explosions themselves became space debris. The 1981 destruction of the Soviet Kosmos 1275 remains unexplained, but was possibly due to space debris, and the same may be true of the 1986 explosion of an Ariane rocket. Then there are the seemingly mundane (but in fact potentially deadly) encounters with small bits of debris, such as the paint fleck that struck the Space Shuttle Challenger in 1983 and caused $50,000 worth of damage, plus the disruption caused to launches and space station activities when there is a projected possibility of a debris collision. The “weaponization” of space, including the use and testing of anti-satellite weaponry, may also increase the amount of fragmentation debris. The 2007 Chinese anti-satellite test in LEO may have created “a cloud of more than 3,000 pieces of space debris.” During the Cold War, the intentional destruction of satellites for national security reasons may have had a similar effect.

In an exhaustive 1989 study, Howard Baker identified four categories of space debris:

- “inactive payloads” – “former active payloads which can no longer be controlled by their operators”; a category that includes spent orbital satellites and probes;

- “operational debris,” i.e., “objects associated with space activities” that remain in space, mostly comprising “launch hardware” but also other man-made materials discarded in the course of space exploration. Hardware items include rocket bodies, orbital transfer vehicles, kick motors, nose cones, payload separation hardware, “exploded restraining bolts,” “fairings,” “exploded fuels tanks and insulation” and “window and lens covers”;

- “fragmentation debris” caused when objects break up after explosions; and

- “micro particulate matter” between 1 and 100 microns wide, including particulates from solid-fuel transportation systems.

The nature of the problem varies according to orbit. The low earth orbit (LEO) is closest to the atmosphere, medium earth orbit is between 5,600 to 36,000 kilometers (often used for navigational satellites), while geosynchronous orbit (GEO)—the very valuable orbit utilized by many communications satellites—is a higher orbit. Debris in LEO is more likely to be dragged down to the atmosphere and thus may diminish over time, but travels at enormous speed relative to other objects. Orbital debris in GEO, which “moves in an enormous doughnut shaped ring around the equator as the gravitational forces of the Sun, Moon and Earth pull on the objects,” is “not naturally removed from orbit by atmospheric drag,” and thus is “estimated to last anywhere from a million to 10 million years.”

Moreover, it has been estimated that collision risk in the GEO “is not uniform by longitude,” but instead is “seven times greater in regions centered around the so-called ‘geopotential wells’ which exert a gravity pull on drifting satellites and other debris.” According to the insurer Swiss Re, there are operating satellites worth “hundreds of millions of dollars” that are “in or near these locations.”

Some scientists have warned that the risks posed by space debris may grow, perhaps exponentially, as the use of space increases. One theory, developed by NASA scientists John Gabbard and Donald Kessler (and dubbed “the Kessler Syndrome”), posits that the population of human-generated space debris might hit a critical mass. One writer explains:

Proponents of the cascade effect hypothesize that large space debris pieces will increasingly collide, break apart, and fill the orbit with smaller and more numerous bits of debris. These smaller pieces of debris will further collide and break apart, creating more fragments and increasing the chance of new impacts. When the space debris population reaches a certain threshold, collisions between objects will create so much new debris that it will increase independently of further space operations. Left unchecked, this self-generation could actually create a debris belt around the Earth.

On this theory, the “collisional cascading” process will “pose a greater risk to spacecraft than the natural debris population of meteoroids.” Indeed, some consider that debris is already expanding at an “astonishing” rate, and that without proper mitigation “[e]arth’s orbit, and eventually the entire solar system, will become an unusable wasteland of dangerous debris.”

The risks posed from space debris have attracted attention from the insurance sector. In a recently-published study, Swiss Re observed that that orbital debris had doubled over the last 20 years, and warned that “debris has the potential to damage or destroy high-value, operational satellites with resulting revenue losses in the billions of dollars or euros.”

II. Calls for action and policy proposals

The principal response to the “debris” issue has been “mitigation”: the adoption of guidelines to modify spacecraft design to reduce the amount of space debris created in flight, such as those adopted by the United Nations Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) and NASA , as well as the reporting and tracking of existing space junk. Other mitigation practices include the de-orbiting of inactive satellites (if in LEO), or (if in GEO) their removal from active orbit of inactive satellites and their placement in retirement orbits.

Some call for more vigorous action. Writing in 1990, Albert Gore stated that “[o]rbital debris [was] already a problem of considerable importance; consequently, laws to control further proliferation will be needed.” Commentator Brian Weeden has called for the introduction of an enhanced, more comprehensive debris tracking system and other technologies to reduce debris. Others have called for the creation of a “superfund” or multilateral treaty system to subsidize remediation efforts/research, as well as bans of particular kinds of material (e.g., nuclear fuel) in orbit. A possible variant is the creation of “market share” or polluter-pays system where space users are required to “purchase” the ability to create debris.

Other more ambitious projects would include the recapture of defunct satellites, perhaps aided by a maritime-style “salvage” regime. Technologically, however, the options are limited:

One involves sending a satellite to known debris and either capturing the debris or attaching a device (tether or engine) that would enable the debris to reenter Earth’s atmosphere. The primary problem with this concept is that the propellant expenditure to visit more than one piece of debris per launch is enormous… The only other potential remediation measure involves using ground-based lasers to perturb the orbit of debris and cause it to reenter the Earth’s atmosphere more quickly. However, the tracking ability of lasers, the ability to discriminate among active satellites and debris, and the high energy levels required to have any noticeable effects makes this proposal currently impractical.

On this view, “currently there are no economically or technically feasible ways to remove space debris from space.”

III. Do the OST and Liability Convention regulate space debris?

A. The Legal Framework

The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 (OST) articulates a series of governing principles about the use and exploration of space that, while extremely important to space law generally, do not directly address the status of space debris. Among other things, the OST provides that space is the “province of all mankind”; that the “exploration and use of outer space [shall be conducted] in accordance with international law,” that states are generally responsible for the activity of their nationals in outer space; that states “shall retain jurisdiction and control” over “objects launched into outer space” and shall generally be “liable for damage” from such objects; and that states shall avoid “harmful contamination” of space and activities that interfere with other states’ rights and exploration.

In a Liability Convention signed in 1972, contracting states agreed to create absolute liability for damage on the surface of the earth (or to aircraft) “caused by its space object[s],” and further imposes “fault”-based liability on states for damages “caused elsewhere than on the surface of the earth to a space object of one launching State or to persons or property on board such a space object by a space object of another launching State.” Inter-state claims may be resolved through “Claims Commissions”; a quasi-arbitral procedure.

These presuppose that governments are responsible for many facets of space travel and that the principal claims arising in space law will be government-to-government in nature. This is a product of the era in which they were negotiated. As one commentator remarked of the OST:

Because it was drafted at a time when space activity meant rare and expensive government forays, little attention was paid to the possibility of pollution of the space environment. Instead the provisions of the treaty focused on ensuring freedom of access and forestalling the exercise of national control, not operational efficiencies.

B. Arguments in favor of liability for launching states

None of the space treaties contains a “per se” ban on “[l]ittering the outer space environment” or specific rules about space debris. Thus, arguments for state liability for space debris have often been based upon the more general statements contained in the OST, particularly Article VII, which provides:

Each State Party to the Treaty that launches or procures the launching of an object into outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, and each State Party from whose territory or facility an object is launched, is internationally liable for damage to another State Party to the Treaty or to its natural or juridical persons by such object or its component parts on the Earth, in air space or in outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies.

| If its definition of “space object” includes “component parts of a space object as well as its launch vehicle and parts thereof,” were viewed as including the remnants of all launched objects, then states may be potentially liable for damage caused by debris that could be traced back to it. Things, however, are not that simple. |

As all space debris originates from materials launched into outer space, it might be argued that any piece of space debris is an “object[s] launched into space” and that collisions involving such “objects” trigger the international liability provisions of Article VII of the OST. The “liability” on states established by Article VII is fortified by Article VIII, providing for states to “retain jurisdiction and control” over “objects launched into outer space,” as well as Article VI, providing that states are generally responsible for the activities of all of their nationals—public or private—occurring in space. Indeed, although Article VI’s reference to responsibility is somewhat “vague,” its terms state that the “activities” of “non-governmental entities” in outer space are to remain subject to “authorization and continuing supervision” of the appropriate state parties. On this view:

Because non-governmental entities may conduct activities in outer space only with the authorization of and under the supervision of the appropriate nation, any liability of such an entity is imputed to the nation-state which authorized its space activities. In this way, article VI renders the nation-state liable for the activities of non-governmental entities.

A similar line of argument could be made with respect to the Liability Convention, using its fault-based liability for in-orbit collisions. If its definition of “space object” includes “component parts of a space object as well as its launch vehicle and parts thereof,” were viewed as including the remnants of all launched objects, then states may be potentially liable for damage caused by debris that could be traced back to it. Things, however, are not that simple.

C. Legal uncertainties concerning launch state liability for debris

At the most basic level, there remains uncertainty over the meaning of “space object”/“object launched into space” for purposes of the OST and the Liability Convention. Manfred Lachs reportedly considered that “a space object is any object to be placed in orbit as a satellite of the earth, the moon or any other celestial body to traverse some other course to, in or through outer space.” Cheng considered that a space object is anything launched into space, even “a lump of rock launched into outer space for no reason at all but the fun of it.” Thus, on an expansive view, even “non-functional space objects” remain “space objects.” “[S]hattered fuel tanks or flakes of paint from space objects” will be treated as “space objects.” So, according to Cheng, will “refuse generated in space.”

But space debris creates additional problems. While it could be argued that an intact (but non-functioning) satellite is a “space object,” can the same be said of an exploded satellite? Are “fragments from a space object” a “space object”? Cheng considers that they might be, but also considered that states may disclaim ownership in discarded or disused objects, rendering them owner-less, or res derelicta. But this remains controversial. Baker, while noting the United States position that “space refuse” is potentially a “space object” for purposes of the Liability Convention and OST, nevertheless considers the issue to be “unclear” He further observes:

…The status of inactive satellites and spacecraft is uncertain, since Article I(d) [of the Liability Convention] gives no indication as to whether a payload must be active to qualify as a “space object.” If, however, “space object” is defined as an object “designed for use in outer space,” then inactive payloads would not be included.

Article III of the Liability Convention imposes liability upon states for in-orbit collisions that are “its fault or the fault of persons for whom it is responsible.” But it is silent on the standard for determining “fault” with regard to a particular object, and thus silent on how “fault” can be ascribed for space debris (assuming this to be a space “object”). Some might argue that the “gap” is filled by the IADC Guidelines establishing standards with respect to debris mitigation, but this is not a universal consensus and the guidelines by no means resolve all controversies.

This is exemplified by the academic debate over the Kosmos 2251/Iridium crash of 2009 (an incident that, officially at least, does not seem to have given rise to any liability claims at this date). Even assuming Iridium’s activities were attributable to the US (per Article VII of the OST), determining the applicable “fault” standard remains problematic. As for Kosmos 2251, some might criticize Russia for failing to de-orbit this satellite when it became inactive in 1995. But although under today’s remediation standards, it may be appropriate to de-orbit a defunct satellite, this was arguably not the case in 1995, when Kosmos 2251 ceased to be active. Indeed, in 1995, “nations routinely abandoned unused or decommissioned satellites.”

Furthermore, although the OST “imputes” private actions to states, there is some doubt as to whether this rule holds true for the Liability Convention, which “does not specifically incorporate the Outer Space Treaty’s doctrine of imputability.” Some have therefore argued that it is “unclear whether a respondent under the Liability Convention will be liable for damage caused by its nationals under the Outer Space Treaty.”

Article I(a) of the Liability Convention defines “damage” as “loss of life, personal injury or other impairment of health; or loss of or damage to property of States or of persons, natural or juridical, or property of international intergovernmental organizations.” Article VIII(1) permits “[a] State which suffers damage, or whose natural or juridical persons suffer damage” to make claims, and Article XII calls for compensation to be

determined in accordance with international law and the principles of justice and equity, in order to provide such reparation in respect of the damage as will restore the person, natural or juridical, State or international organization on whose behalf the claim is presented to the condition which would have existed if the damage had not occurred.

But beyond those general statements, the Convention does not indicate clearly whether “damage” extends to the costs of environmental remediation or of other injury that did not directly affect life or economic property. This became evident during the Kosmos 954 episode, where the main “damage” claimed was the cost of environmental cleanup to property that was not being used for farming or industrial use. Although the Soviet Union eventually paid around half of the C$6 million claimed by Canada as part of a voluntary settlement, the Canadian side was initially concerned that the Soviets might deny the existence of any “damage” under the Liability Convention. This “illustrate[d] one of the Liability Convention’s main weaknesses: its definition of damages is too vague.”

| There are serious practical issues in actually identifying the source of a collision, especially for fragmentary debris. |

It has been argued that space debris triggers Article IX of the OST, which obligates states to avoid “harmful contamination” of space. Others, however, maintain that Article IX refers only to biological contaminants, with the result that it applies only to materials that could affect astronauts and spacecraft—not debris. Some have argued that “debris” was not intended to be regarded as “harmful contamination,” because it is “impossible to operate in space without creating some amount of debris,” and thus it would have been odd for Article IX to have applied to a seemingly inevitable byproduct of space exploration. Similarly, while Article V of the OST requires states to report “phenomena” that may be “a danger to the life or health of astronauts,” some question whether space debris is a “phenomenon” for purposes of this article.

Furthermore, Article IX’s obligation to “consult” with other users about activities that might cause causing “harmful interference” the use of outer space is hardly an “absolute injunction” against such activities, and, in any event it only applies to “future planned space activities,” not “activities already completed,” meaning that Article IX, even if applicable, may be of little utility in dealing with space debris (which usually is created through past activities).

There are serious practical issues in actually identifying the source of a collision, especially for fragmentary debris. For example, “[i]f a piece of debris one centimeter in diameter destroys a space station, it would be nearly impossible to find that piece of debris after the disaster and identify it.” This problem, combined with the absence of a fault standard, can “make recourse under the Liability Convention largely futile.” The same can be said of Article VII of the OST, which “does not indicate what recourse a participating State has if the damaging debris is unidentifiable.”

The Liability Convention’s dispute resolution provisions, which envisage state-to-state dispute resolution, are expressed as being without prejudice to a private party’s ability to bring claims in the “national courts” or agencies of contracting states. In the absence of legislation or precedent on the issue, however, it is far from clear how the world’s various national courts would handle the matter.

In sum, the OST and Liability Convention provide “minimal specific guidance to the drafters of a space debris framework.” One observer has said that “‘it is apparent that any prohibition on the generation of space debris could only be found in the spirit of the treaty and not in its text.’“

D. Calls for legal reform

Many have called for a better-defined treaty regime to govern space debris. Taylor, for example, argues forcefully that the jurisdictional and control rule in Article VIII arguably is “an impediment to proposed solutions for the orbital debris problem,” and that there is an urgent need to define “space object” “to make clear that it applies to orbital debris.” He further argues that, although voluntary mitigation is commendable, “[t]he current lacuna of international law concerning orbital debris needs to be filled with enforceable rules and definitions that provide certainty and accountability.” A new regime, he acknowledges, might involve collective and individual sacrifices (in terms of fuel carrying, mission life, other costs), but considers these justified in the interests of a safer environment.

Others warn that this is not a “realistic possibility,” given the slow-moving nature of the UN’s space law committees. For its part, the United States took the position in 2004 that it was “premature” for the UN subcommittee to consider the legal aspects of space debris.

IV. Customary international law

Treaties represent but one source of law; existing alongside “international custom, as evidence of a general practice accepted as law,” as well as “the general principles of law recognized by civilized nations.” To prove customary international law as to a particular proposition the proponent must generally show the existence of a rule of law, as evidence by “extensive and virtually uniform” practice of states, “including that of States whose interests are specially affected,” that show conformity to the rule in question, accompanied by opinio juris, i.e., that the states have conducted themselves “in such a way as to show a general recognition that a rule of law or legal obligation is involved”).

| The existing uncertainty ought to incentivize all users of space—states and private entities alike—to remain focused upon the issue and to work together to find a more definite and predictable means of addressing it. Unlike space, the law abhors a vacuum. |

Some treaties have been held to represent a codification of law; other treaties, if drafted by a wide membership of the international community, may be viewed as “binding upon all members of the international community” even prior to ratification “because [they] embod[y] or crystallize a pre-existing or emergent rule of customary law”. In this vein, commentators such as Cheng have viewed the OST’s terms, except the “registry” requirement, are “declaratory of general international law.” Moreover, Article III of the OST, requiring states to carry on the exploration and use of space “in accordance with international law,” may further indicate that the rules of customary international law, as they apply between states, extend to space activities.

Customary international law has been said to impose an obligation “‘not to allow knowingly [a state’s] territory to be used for acts contrary to the rights of other States.’“ This doctrine, known by some as the “transboundary rule,” was expressed as follows in the Trail Smelter arbitration:

[N]o state has the right to use or permit the use of its territory in such a manner as to cause injury… in or to the territory of another or the properties or persons therein, when the case is of serious consequence and the injury is established by clear and convincing evidence.

The ICJ in Corfu Channel, finding Albania liable for minefields placed in its territorial waters, likewise referred to “every State’s obligation not to allow knowingly its territory to be used for acts contrary to the rights of other States.” In a similar vein, the 1972 Stockholm Declaration called upon states to “ensure that activities within their jurisdiction or control do not cause damage to the environment of other States or of areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction. In the 2009 Pulp Mills case, the ICJ, after reaffirming the Corfu Channel principle of prevention, held:

A State is thus obliged to use all the means at its disposal in order to avoid activities which take place in its territory, or in any area under its jurisdiction, causing significant damage to the environment of another State. This Court has established that this obligation “is now part of the corpus of international law relating to the environment”.

In his study on space debris, Baker tied this principle to the provisions of the OST. Article VI, he observed, extends state responsibility to activities “carried on by non-government entities” and requires states to “assur[e] that national activities are carried out in conformity with the provisions” of the OST, including through “authorization and continuing supervision” by the applicable states. These may support a “heightened duty to protect other States”; thus, he argued, “the effect of Articles II and VI of the [OST] is to apply the Corfu Channel and Trail Smelter principles to governmental and non-governmental activity in outer space and to heighten a State’s duty of due diligence. Put another way:

“In the absence of any specific agreement to the contrary, there is a customary rule of international law which provides that States, either individually or together with other States in international organizations, are liable for damages caused to other States through acts committed within their jurisdiction, particularly where those acts are committed with a high degree of State participation and supervision. Launching of space objects would appear to fall within that kind of category.”

This proposition will remain hotly debated (and, indeed, the concept of “jurisdiction” may be hard to translate to a space context). The closest there has been to an acknowledgment of such a rule was the Soviet Union’s acceptance of financial responsibility in the Kosmos 954 incident of 1978 in response to Canada’s claim under both the 1972 Convention and “general” principles of international law. Even then, the eventual payment, made grudgingly, was expressed as voluntary and without admission – meaning its status remains debatable.

It remains difficult to ascertain the precise boundaries of the OST or Liability Convention as regards space debris, and equally difficult to ascertain customary international law (if any) on the same topic. This uncertainty, however, cuts both ways, because it clouds future investments in space and complicates the process of insuring space risks. Beyond the continuation and broadening of existing mitigation guidelines, a case can thus be made for some kind of reform that will limit and/or cap the liability of space users who have observed certain basic precautionary practices, either in design or deployment of spacecraft.

The existing uncertainty ought to incentivize all users of space—states and private entities alike—to remain focused upon the issue and to work together to find a more definite and predictable means of addressing it. Unlike space, the law abhors a vacuum.