The gift of a Europa mission may have a costby Jeff Foust

|

| “We’re selecting instruments this spring and moving towards the next phase of our work,” NASA administrator Bolden said of Europa mission plans. |

And, sometimes, the budget proposal includes some gifts independent of the impending fiscal fray. For advocates of a mission to Europa, the moon of Jupiter thought to have a subsurface ocean of liquid water and thus potentially hospitable to life, the budget proposal included one such gift for them: a decision by NASA to press ahead with such a mission.

Specifically, the budget proposal states that the proposed mission will reach a milestone known in NASA programmatic jargon as “Key Decision Point A” this spring. Assuming a positive review, the Europa mission will move from the current series of “pre-formulation” concept studies into a formal project, although still in an early phase.

“In FY [fiscal year] 2016, the project will formulate requirements, architecture, planetary protection requirements, risk identification and mitigation plans, cost and schedule range estimates, and payload accommodation for a potential mission to Europa,” NASA’s budget proposal states. “The leading mission concept may require significant modification depending on what researchers learn in FY 2015 about the existence of active plumes from Europa’s south pole and the accommodations requirements in the awarded instrument proposals.”

That last sentence refers to awards that NASA plans to make in the next few months for instruments that the Europa spacecraft may carry, based on proposals requested last year. “We’re selecting instruments this spring and moving towards the next phase of our work,” NASA administrator Charles Bolden said in a “State of NASA” speech last Monday at the Kennedy Space Center.

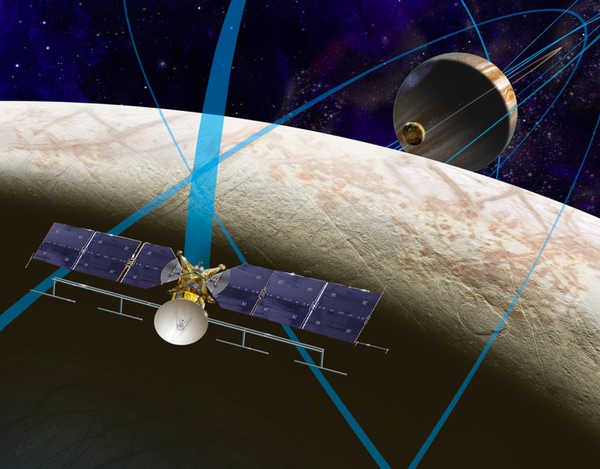

While the Europa mission included in the budget request isn’t given a specific name, the concept under study is widely known as “Europa Clipper.” Previous Europa mission designs, including one that ranked second highest among large “flagship-class” missions in the latest planetary science decadal survey, involved placing a spacecraft into orbit around the moon. Europa Clipper would instead put a spacecraft into orbit around Jupiter, with a large number of flybys of the moon.

The NASA teams, the budget proposal states, found “that NASA could accomplish over 80 percent of the science that a Europa Orbiter would achieve for about 50 percent of the cost with a mission that stays in Jupiter orbit and conducts many focused flybys of Europa.” No specific price is mentioned, but past reports indicated that Europa Clipper would cost on the order of $2 billion.

The budget document also confirms one development with Europa Clipper that those working on the project hinted at several months ago: the spacecraft would use solar, rather than nuclear, power. Past missions to the outer solar system have all used radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) to generate power; the Juno spacecraft, en route to Jupiter, will be the first to use solar power.

| “We’ve heard the message from our members that Europa must be a priority for NASA, and we are pleased to see the Administration take the same view,” said The Planetary Society’s Dreier. |

“For the last two years, we did extensive risk reduction work looking at whether solar is feasible,” said Thomas Magner of the Applied Physics Laboratory, in a presentation in October about the mission at the International Astronautical Congress in Toronto. “We found that solar works fine, so our final decision about two months ago was to go to solar.”

Using solar power, he said then, would lower Europa Clipper’s cost over an RTG-powered version, although he didn’t specify the difference. The spacecraft would be heavier to accommodate the large solar power array needed to operate that far from the Sun, but he said it was well within their design margins.

At the Toronto meeting, Magner was optimistic that NASA would move forward with the Europa Clipper design, noting it passed a mission concept review “with flying colors” in September. “We’ll get a new start early next year,” he said then.

NASA’s decision to follow through on that, and formally start Europa Clipper as a project within the next few months, was warmly welcomed by planetary exploration advocates, who have for years—decades, even—sought such a mission.

“Tens of thousands of individuals around the world wrote to Congress and White House last year asking for this mission to Europa,” said Casey Dreier, director of advocacy for The Planetary Society, in a statement the organization issued after the release of the budget. “We’ve heard the message from our members that Europa must be a priority for NASA, and we are pleased to see the Administration take the same view.”

“It’s a huge deal,” Dreier said in a separate interview. “We cannot be more excited about it.”

That decision to proceed with Europa does have its hitches, though. NASA is requesting just $30 million for Europa mission studies. While twice the $15 million the agency requested in its 2015 budget—the first time the mission was a line item in the agency’s budget proposal—it’s far less than the $100 million Congress provided for Europa mission studies in the final 2015 appropriations bill passed in December. Congress also provided more than $150 million in previous years to support studies of Europa mission concepts.

In a conference call with reporters last Monday to discuss the NASA budget proposal, NASA chief financial officer David Radzanowski said the requested funding is part of a five-year budget profile that would gradually increase the project’s budget to $100 million a year by 2020. “This budget does assume a five-year funding profile for a mission to Europa,” he said, a funding profile “that would assume a launch in the mid-2020s.”

Some in Congress would like NASA to accelerate the development of the Europa mission. A NASA authorization bill being introduced this week—and scheduled to be voted by the full House as soon as Tuesday afternoon—would direct NASA’s planetary science program to include “a Europa mission with a goal of launching by 2021.”

Europa advocates also have increased influence in the House Appropriations Committee. Rep. John Culberson (R-TX), perhaps the biggest supporter of Europa exploration in Congress, is now the chairman of that committee’s Commerce, Justice, and Science subcommittee, whose funding jurisdiction includes NASA. His support of a Europa mission is widely considered the main reason why the mission has received as much funding as it has so far.

Moreover, while NASA’s support of a Europa mission in the budget request, despite differences in dollar amounts, has widespread support, other elements of NASA’s planetary sciences budget are facing opposition. In particular, NASA is requesting no funding for the Mars rover Opportunity or the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter for fiscal year 2016, and zeroes out the Mars Odyssey orbiter in 2017.

That move saves only a modest amount of money: Opportunity cost $14 million in 2014, the most recent year budget numbers for the mission are available, and LRO $12.4 million. That combination, some noticed, is close to the $30 million NASA is requesting for Europa.

NASA tried something similar last year, including no funding for LRO and Opportunity in the 2015 budget request, although NASA asked for $35 million in a supplemental funding package, the Opportunity, Growth, and Security Initiative, for extended planetary science missions. At the time of the 2015 budget request, NASA was still performing a “senior review” of ongoing planetary missions, and had yet to decide which ones were worth extended missions.

| “Last year, Congress sent a message to the Administration not to short-change planetary science, and sadly that message was not received,” said Rep. Schiff. |

That senior review, completed in September, looked favorably on both LRO and Opportunity. LRO got a rating of “very good/good,” while Opportunity got a rating of “excellent/very good,” and recommended both missions continue. “The Mars Exploration Rover (MER) Opportunity continues to make important scientific discoveries on the surface of Mars,” the senior review report noted.

The 2016 NASA budget request, though, noted that a number of technical problems, including issues with the flash memory onboard the rover, weighed against continuing the mission. “After a long, productive mission life, Opportunity has started to show signs of age, including recent problems with its flash memory,” the budget proposal stated. “NASA plans to end Opportunity operations by FY 2016.”

The Planetary Society, among others, expressed opposition to the decision to eliminate funding for those missions. “We urge Congress to work to rectify these unfortunate steps, and to preserve the operating missions that are rated highly in the independent planetary science senior review process,” the organization said in its statement.

Some in Congress already plan to take action about that. “Last year, Congress sent a message to the Administration not to short-change planetary science, and sadly that message was not received,” said Rep. Adam Schiff (D-CA), whose district includes NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in a statement issued by his office. “The Administration once again zeroed out funding for two working vehicles—the Mars Opportunity Rover and Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter—effectively shutting down instruments still providing and producing valuable science.”

Congress may indeed act, as Schiff request, to restore funding for LRO and Opportunity, and to increase funding for Europa. Where that money would come from, though, becomes a broader policy question. The 2016 request for NASA planetary science overall of $1.36 billion is more than the $1.28 billion it requested last year, but less than the $1.44 billion included the final 2015 appropriations bill. (That number could change slightly as NASA completes its operating plan for the year, allowing it to shift some funding not explicitly allocated in the sending bill around various programs.)

That 2015 budget was helped by an overall increase of more than $500 million in the final bill compared to the original request, allowing appropriators to increase planetary and other science funding while limiting the cuts it had to make in other programs. The 2016 request already includes an increase of more than $500 million again above the final 2015 spending bill. That, coupled with increased fiscal pressures (including the possible return of budget sequestration) may make it harder for appropriators to support planetary science programs without taking the money out of other agency efforts.

That could mean members of Congress, and planetary exploration advocates, could be facing some tough decisions in the coming months. That gift of a Europa mission could come with a price.