One last first timeby Dwayne Day

|

| This was pre-Internet days, of course, and so the primary way of getting information about the Voyager mission was the evening news (or special programs like ABC’s Nightline), or waiting for the newspaper or news magazines to show up. It was before the era of instant gratification. |

Rochester has cold winters, but spring and summer and fall can be beautiful. Its location on Lake Ontario results in clear skies and comfortable temperatures, and I remember that the weather was great that late August, 1989. I also remember that I had asked out a young woman that I fancied. We had gone to the planetarium before, for “Laser U2.” Yes, U2—primarily from their incredible Joshua Tree album—and laser beam images projected on the planetarium dome. But much of that summer she was busy with a new job. I got the sense that we were stuck in friend-zone, and I wanted to try and change that and thought the Neptune show was my opportunity.

Because life is full of coincidences that really are not all that coincidental, someone that I didn’t know then, but became friends with a decade later, was also involved in that Strasenburgh Planetarium show. Rob Landis, who now works for NASA on the agency’s asteroid detection program, was at the time an intern at the planetarium and knew how to run all the equipment. “We started it because we thought it would be historic and interesting,” Landis remembers. “The planetarium director at the time wasn’t so keen on it,” he said in a recent email. The director thought that nothing much was going to happen, and Voyager 2’s previous encounter at Uranus in 1986 had not attracted much attention. “But, if we wanted to do something… fine. We could,” Landis remembered the director conceding. “It was an unexpected success.”

Steve Fentress, who is now the Strasenburgh’s director, was then on staff at the planetarium and also remembers the Neptune encounter. “My late father had been a network television news producer, and I remember him going to work at crazy hours to work on coverage of the Gemini and Apollo missions,” Fentress recounted. “I had had a couple of temp jobs as an audio-visual technician at JPL, working on von Karman Auditorium press conferences and Blue Room status reports for the Viking landings and the Voyager Jupiter and Saturn encounters. So I was ready to do a special event.”

The planetarium had a satellite TV receiving system that they had acquired for an ocean education event called the JASON Project. “Our senior technician Carl Dziedziech got the antenna pointed at the NASA TV satellite, and we recorded the Voyager Neptune broadcasts on 3/4-inch UMatic videotape. Each day we compiled video highlights by recording back and forth between two decks, without video switchers or any other appropriate equipment. Al Hibbs, Laurence Soderblom, Andrew Ingersoll, Ed Stone, and other Voyager scientists and engineers were familiar figures on our screen,” Fentress recalled. Soderblom is the scientist who discovered active geysers on Neptune’s moon Triton. In another one of those not-so-unusual coincidences of life, decades later I worked with Soderblom, but didn’t realize that he had discovered the geysers until our job was over.

“JPL had produced an educator’s guide,” Landis added. “We put together a combination video/short show with visuals describing what the Voyager missions had done up to that point, and this required live narration. Usually it was me or Steve. We would then transition into the ‘tonight’s news from Neptune’ portion and this feature constantly changed from night-to-night as we prepared our material from the latest ‘Blue Room Reports’, press conferences, etc. as events unfolded at Neptune.” Landis would also regularly check his CompuServe email account to see if there was any additional news.

“What was great about the media guide is that we had a damned good idea of what imagery would be coming down when and could anticipate our ‘live’ show for that night.” So about an hour or so before their presentation they had finalized what they would do, leaving plenty of time for questions and answers from the audience.

Unlike New Horizons, which can either point its instruments at the target or point its antenna at Earth, but not both at the same time, Voyager 2 had a scan platform for its instruments and could simultaneously take data and point back home. This provided a continuous stream of imagery and other information back to Earth over a short period of time—a few days. “Not too many days, not too few to make a publicity splash,” Fentress recalled.

“I think we offered ‘Neptune Tonight’ free to members if they would phone in for a reservation,” Fentress explained. “Our planetarium secretary (we had such a person in those days) would have her phone resume ringing instantly after hanging up from the previous reservation call. I think we were at capacity on at least a couple of nights.”

Fentress also fondly recalled running out of videotape and calling the supplier for an emergency delivery. The man who showed up in the delivery truck said ,“I think what you kids are doing here is fantastic.”

| I figured that the Neptune encounter event at the planetarium might be my last opportunity for a romantic encounter—sorta like sitting out underneath the stars, but different. Better, because it was unique. |

The planetarium’s “Neptune Tonight” was quite successful, and later in 1994 they repeated it with special programs on the crash of comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 into Jupiter. “Now, with New Horizons, Dawn, and Rosetta-Philae going at the same time, it’s happening again,” Fentress added. “What the Strasenburgh Planetarium needs to really bring our audience into the new era is a modern digital full dome visualization system like those installed at other large planetariums in the last 20 years,” he said. New Horizons, unlike the Voyager 2 encounter at Neptune, is going to send data back over a much longer time, so the planetarium can play that out better rather than a short intense see-it-or-miss-it event.

As for me, by late August I was running out of time to connect with the young woman before I left for a semester in England, and I figured that the Neptune encounter event at the planetarium might be my last opportunity for a romantic encounter—sorta like sitting out underneath the stars, but different. Better, because it was unique. Maybe afterwards we’d go out for ice cream. And maybe after that I’d try to kiss her.

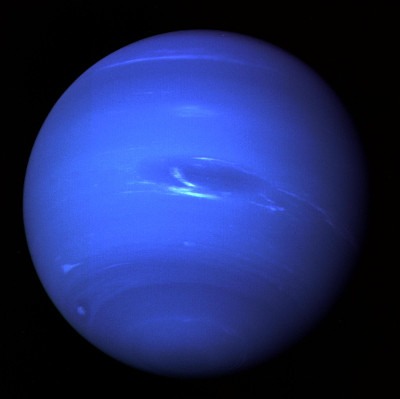

She turned me down. She was busy with work. Couldn’t make it. So I went by myself. I had a great time. I learned fascinating things about Neptune while staring at images of that blue globe projected on a planetarium dome. I cannot remember if I learned about Triton’s geysers then or later, but when I did they fascinated me. The solar system is full of wonderful surprises.

I walked out of the planetarium into a warm August night and the sky was clear and the stars were out. I was in a great mood. I only wished Laura had been there to enjoy it with me.

A few days later she called me up and said that she had time to go with me to that Neptune thing. No, I told her. It was over. It was a one-time deal. A week or so later I hopped on a jumbo jet and flew to England for my internship in the British Parliament. I didn’t really see much of her after that. Sometimes these opportunities come by only once, fleeting, and then they’re gone.