Echoes from the past: the Mars dilemmaby John Hollaway

|

| Reusability is the key to SpaceX’s strategy to put humankind permanently on Mars, hence the critical importance of SpaceX’s recent successes in safely landing Falcon 9 first stages. There will be no stopping SpaceX now—except money. |

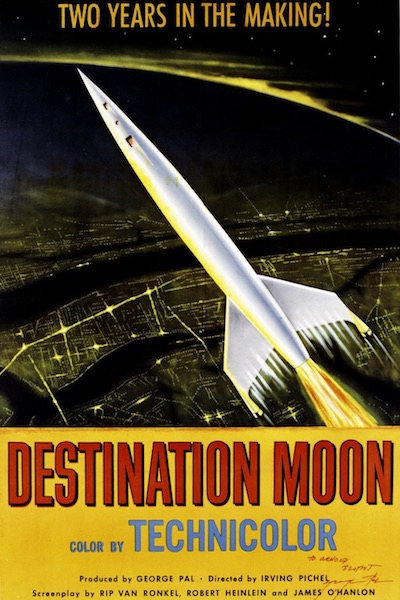

There was another parallel. The film’s premise was that US private industry would have to finance and manufacture the first human mission to the Moon because of the inability of US government agencies to meet the challenge. Substitute “Mars” for “Moon” and we get Elon Musk’s strategy and his driving vision. The film argued that once the private sector had shown the way, the (embarrassed?) government would put in the necessary resources to enable the United States to take up a dominating position in space.

Reusability is the key to SpaceX’s strategy to put humankind permanently on Mars. In 2012 Musk said, “The revolutionary breakthrough will come with rockets that are fully and rapidly reusable. We will never conquer Mars unless we do that. It’ll be too expensive. The American colonies would never have been pioneered if the ships that crossed the ocean hadn’t been reusable.”

Hence the critical importance of SpaceX’s recent successes in safely landing Falcon 9 first stages. There will be no stopping SpaceX now—except money.

So far, SpaceX has been very lucky: its rise has coincided with the growth of venture capital firms and their growing interest in space. Those investors know from the software industry that revolutionary ideas take time to become profitable (Facebook took five years for its cash flow to turn positive.)

| The future market is for launches of numerous small satellites. A reusable vehicle capable of serving this market is what the clever money is watching out for. |

SpaceX has never revealed the development cost of the Falcon series. All that we know is that at a published price of $62 million per launch, Falcon 9 launches are already the cheapest for that class of vehicle in the industry, and are now likely to be much cheaper because the first stages will presumably be sent up again and again. In March, SpaceX president Gwynne Shotwell, said that the price of a launch using a refurbished first stage could potentially fall to around $40 million.

If we assume that its low Earth orbit payload is 15 metric tons (about a third less than full capacity because of the extra fuel needed to land), then the price will only be about $2,700 per kilogram. So if you have something heavy to put into orbit, it is a no-brainer.

And after Falcon 9 comes Falcon Heavy. This will probably lift off later this year and has an enormous payload: up to 53 metric tons to low earth orbit. Nothing has been seen like this since Saturn V.

However, heavy payloads are no longer where the market is. Yes, the International Space Station requires regular cargo missions to keep going, there are still some large geostationary satellites to put up there, and the military has big mysterious payloads. But otherwise the future market is for launches of numerous small satellites. A reusable vehicle capable of serving this market is what the clever money is watching out for.

This lack of a big heavy lift market is why it makes sense for SpaceX to aim for Mars. There will be a great deal of heavy lifting to be done when constructing the proposed Mars Colonial Transporter in orbit. The only snag is, where is the money for this expensive enterprise coming from? The Destination Moon storyline was about provoking the US government into supporting space exploration. Does SpaceX, with its reusable technology and massive lift capacity, aim to provoke government support for the settlement of Mars?

In 1989, President George H.W. Bush suggested human missions to Mars might be a good idea, but then a cost of $450 billion emerged, and nothing more was heard of it. Nevertheless, NASA has consistently stated that it is planning on sending crews to Mars in the 2030s, and to that end is developing its own (perhaps foundering) Space Launch System, and others have proposed less expensive Mars mission architectures. SpaceX could bring this forward by a decade, but the political will has to be there.

| A Mars mission will have prestige and glamour, but it is not a bread and butter vote-getter. The presidential candidates know this. None of them have made an issue of space; indeed, they have tended to avoid discussing it. |

In the 1950s and ’60s, there were good strategic reasons for the US to demonstrate that it could put a man on the Moon if it put its mind to it. There was also the possibility that there would be desirable minerals and metals—rare earths and platinum group metals—to be brought back from there. But in the 21st century there are neither strategic nor commercial reasons for going to Mars. A tiny settlement there could hardly affect Earth’s geopolitics and, unless we run out of iron ore, there seems nothing worth mining.

| A Mars mission will have prestige and glamour, but it is not a bread and butter vote-getter. The presidential candidates know this. None of them have made an issue of space; indeed, they have tended to avoid discussing it. |

Indeed, the challenges to maintaining life on Mars are almost as great as maintaining it on the Moon—and nobody has been back there since 1972 because there is no good reason to do so. Of course, a Mars mission will have prestige and glamour, but it is not a bread and butter vote-getter. The presidential candidates know this. None of them have made an issue of space; indeed, they have tended to avoid discussing it.

So if there are no overwhelming political, strategic, or commercial reasons for going to Mars, when it comes to the point the state won’t pony up the billions needed. This leaves SpaceX stuck with a market that may be too small even to justify its reusable launch prices.

That’s particularly true if a rival system pops up (see “Space launch lite: the Swala concept”, The Space Review, February 29, 2016). The numbers are now available for this very simple system that uses ’50s and ’60s technology. For a development cost of around $176 million, a half-ton payload could be put into LEO for about half a million dollars per launch. For a 20% internal rate of return, the customer pricing would be $3,000 a kilogram. The turn-around could be every two days or so, should the market warrant it.

If I were Elon Musk, I would worry. If I were a US taxpayer, I would breathe a sigh of relief.