Landers, laws, and lunar logisticsby Jeff Foust

|

| “This spacecraft will be the spacecraft that will carry customer payloads to the Moon on our first mission, and many more thereafter,” said Astrobotic’s Thornton. |

That initial optimism has been replaced by delays, but also determination. The prize has been extended several times, and now runs through the end of 2017. The number of teams, which once approached 30, is now down to 16, with some teams working together on getting to the Moon. But at least some of the teams still in the running have emphasized they are making progress, on both technical and regulatory issues, to make the case they’re still in the running—even if they sometimes downplay the importance of the prize itself.

Introducing Peregrine

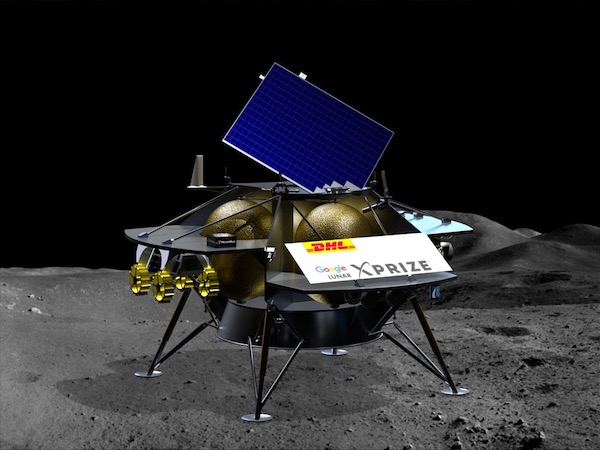

At the Berlin Air Show June 2, Astrobotic Technology, the Pittsburgh-based company that is one of the leading prize contenders, announced the design of a new lander, called Peregrine. It replaces an earlier, and larger, design called Griffin that the company had been working on to land on the Moon.

“This spacecraft will be the spacecraft that will carry customer payloads to the Moon on our first mission, and many more thereafter,” said John Thornton, CEO of Astrobotic, in a June 2 call with media to announce the new lander design as well as new corporate partnerships.

Thornton said the lander’s payload is scalable, depending on the choice of launch vehicle and amount of propellant available. The initial mission, designed to fulfill the Google Lunar X PRIZE requirements and known simply as Mission One, will fly as a secondary payload on a commercial geostationary satellite launch, carry a payload of 35 kilograms to the lunar surface. Later missions, launching as primary payloads, will be able to bring payloads of up to 265 kilograms to the Moon.

A key difference between Peregrine and Griffin, besides the physical size of the lander, is the vehicle’s propulsion system. While Griffin was to use one large engine to land on the Moon, Peregrine will use five smaller ISE-100 engines provided by Aerojet Rocketdyne. The thrusters, which NASA has also studied for use on its own proposed lander missions, are based on Divert and Attitude Control System thrusters Aerojet developed for missile defense systems.

Astrobotic also used the press conference to announce a partnership with Airbus Defence and Space, the largest European aerospace company. Airbus will provide “key engineering support” for Peregrine, Thornton said, under a memorandum of understanding between the two companies.

“For us at Airbus Defence and Space, the Moon is a very important topic,” said Bart Reijnen, senior vice president of on-orbit services and exploration at Airbus Defence and Space. “Astrobotic is what we see as being the frontrunner in the world of commercial lunar transportation.”

| DHL’s Sissing said its collaboration with Astrobotic could later include “extraterrestrial logistics in regard to Moon projects of the future.” |

Astrobotic also announced a partnership with shipping company DHL, who will be the official logistics provider of Astrobotic. That role includes shipping spacecraft components, including the payloads it will carry, to Astrobotic’s Pittsburgh headquarters for integration, and then shipping the completed lander to the launch site.

Arjan Sissing, senior vice president of corporate brand marketing at DHL, suggested its partnership with Astrobotic—which includes the DHL logo prominently displayed on illustrations of Peregrine—could go deeper. That included, he said, “extraterrestrial logistics in regard to Moon projects of the future.”

Peregine is still in its early phases of development: Thornton said the lander was just now approaching preliminary design review. At the press briefing, he declined to offer a specific schedule for the mission, including whether he felt that the lander would be ready to Mission One by the prize deadline of the end of 2017.

The focus now, he said, is lining up payloads in addition to the ten already signed up—including rovers from two other teams—and getting them in place on the lander. “We will fly once all the payloads are ready,” he said.

Thornton, though, is aware of a closer deadline: a requirement to have a signed launch contract, validated by the X PRIZE Foundation, in place by the end of this year. Teams that do not make that deadline will be dropped from the competition. So far, only Moon Express and SpaceIL have announced launch contracts for their lander.

Astrobotic plans to join them, Thornton said. “X PRIZE has a deadline of getting a launch by the end of this year, and our goal is to do just that, to be on a manifest and ready to go,” he said.

Getting regulatory approvals

While Astrobotic has been working on its Peregrine lander, Florida-based Moon Express has been tackling a very different, yet still very challenging, issue: winning regulatory approval for its lunar lander.

Moon Express, like a number of companies planning so-called “non-traditional” commercial space activities—which ranges from lunar landers and asteroid prospecting missions to commercial space stations—is facing a gap in US law regarding how the government carries out its obligation under Article VI of the Outer Space Treaty regarding “authorization and continuing supervision” of space activities.

For communications and remote sensing satellites, the responsibilities to carry out that treaty obligation fall to agencies like FCC and NOAA, who license such spacecraft. But there are no clear responsibilities for those non-traditional missions, leading the State Department to argue it could not approve payload reviews for those missions, a key step in the launch licensing process.

| Richards likened the ongoing regulatory uncertainty to the state of commercial suborbital spaceflight prior to the 2004 flights of SpaceShipOne. “We’re facing the same thing with the Google Lunar X PRIZE.” |

In April, Moon Express announced it was filing paperwork with the FAA for a payload review for its lunar lander that comes with additional voluntary information about the mission. That additional information is intended to demonstrate to the State Department and other government agencies how Moon Express would comply with treaty obligations (see “Mining issues in space law”, The Space Review, May 9, 2016).

The outcome of that review has not been disclosed, although there have been rumors for a few weeks, including an article last week in the Wall Street Journal, that Moon Express would win approval. However, it remains a major obstacle to that company, or other US-based firms planning lunar missions.

Moon Express CEO Bob Richards, speaking at a June 7 panel at the Library of Congress in Washington after the screening of parts of the documentary series Moon Shot about the prize competition (see “Review: Moon Shot”, The Space Review, March 21, 2016), said he had initially ranked regulatory issues third after financing and technology in terms of challenges his company would face.

“There’s been an interesting inversion to that,” he said, citing the more than $30 million the company has raised and technical progress it’s made on its lander, but ongoing regulatory uncertainty he likened to the state of commercial suborbital spaceflight prior to the 2004 flights of SpaceShipOne. “We’re facing the same thing with the Google Lunar X PRIZE,” he said.

He said his ongoing payload review effort could end that uncertainty. “If the Wall Street Journal is correct,” Richards said, “we’re very close to that happening.”

Astrobotic will have to go through the same payload review process for Peregrine, assuming it launches on an FAA-licensed commercial launch (while the company has not announced a launch contract, DHL’s Sissing did say at the Berlin Air Show briefing that the completed lander would be shipped to Florida for launch.) Thornton, in Berlin, said his company has had preliminary discussions with the FAA on the regulatory process.

“I’m very confident that’s going to get worked out” by the time Astrobotic is ready to launch, Thornton said at the Library of Congress panel.

That modified payload review process, though, is seen as only a temporary fix until a more permanent system that assigns oversight responsibilities to a specific government agency, like the FAA, is approved, likely through legislation.

George Nield, FAA associate administrator for commercial space transportation, said at an American Bar Association space law forum June 8 that even if Moon Express does win approval for its payload review, it doesn’t eliminate the urgency his office, and many in industry, feel for a permanent solution. “What is being looked at right now is a Band-Aid fix because the system is broken,” he said. “There clearly is a problem, and we need to fix that.”

“Moon Express is playing a vital role, and I think that their project demonstrates this is not abstract, this is not theory,” said Mike Gold, chairman of the FAA’s Commercial Space Transportation Advisory Committee. “There are actual projects going on now by the fact that we have not resolved this issue.”

When will they fly?

But as Astrobotic and Moon Express, among other teams, work on various financial, technical, and regulatory issues, the question remains: when will they fly, and does any team have a realistic shot of winning the prize by the December 2017 deadline?

Richards said the launch contract his company has with Rocket Lab includes two launches in 2017 on that company’s Electron small launch vehicle, whose first launch is now planned for late summer. “You’re going to see us flying in 2017, so long as George [Nield] allows us to,” he said. Thornton didn’t discuss a launch schedule at the event.

| “You’re going to see us flying in 2017, so long as George [Nield] allows us to,” Richards said. |

Both companies emphasized that their business plans go beyond winning the Google Lunar X PRIZE. “Prizes are designed not to fulfill the cost of the challenge,” Richard said at the panel. “It’s up to the teams in any X Prize to find that business case.” In the case of Moon Express, that also means flying other payloads to the Moon.

“The reason that we’re here is to build a long-term sustainable business of payload delivery to the Moon,” Thornton said. “That’s our way of contributing to making the Moon accessible to the world.”

But with Astrobotic’s lander still at the PDR level of development, and Moon Express relying on a launch vehicle yet to fly, there are questions about whether either would be ready to fly by the end of 2017, despite the best of intentions. SpaceIL is the only other team that appears to be making serious progress towards a launch by the deadline (its ride is on a Falcon 9, as one of several payloads), but its focus is on educational outreach, rather than establishing a long-term business of lunar missions (see “Still chasing the Moon”, The Space Review, October 12, 2015).

So, there are rumblings in industry that the X PRIZE Foundation and Google might need to extend the prize deadline yet again to keep the prize competition just that—a competition. With companies like Astrobotic and Moon Express planning to move ahead with their missions regardless of the outcome of the current prize competition, the organizers will have to decide whether they need those companies more than the companies need the Google Lunar X PRIZE.