A bittersweet homecoming (part 1)An interview with Jonathan Ward, co-author of Bringing Columbia Home: The Untold Story of a Lost Space Shuttle and Her Crewby Emily Carney

|

| That morning, none of the shuttle’s signature dual sonic booms filled the skies and homes of Central Florida. During a shuttle’s return, this was unthinkable. An eerie silence, instead, shook bystanders to their core. |

Co-author Jonathan Ward (who also authored Rocket Ranch and Countdown to a Moon Launch, both published by Springer/Praxis) added the horrifying coda to Leinbach’s reminiscence: “While the team at Kennedy Space Center wondered where Columbia was, the citizens of Deep East Texas wondered what terrible disaster was being visited upon them from the sky. It was the supreme moment of parallel confusion.” The shuttle was falling in pieces from the sky, breaking up at hypersonic speeds and high altitudes, the victim of an external tank foam strike during its launch phase.

One silver lining emerged from the horrors of that day. Thousands of shuttle program personnel, support teams, and residents throughout affected areas in Texas and Louisiana banded together to complete a near-impossible task: to recover as much of the broken, shattered Columbia as possible. Former shuttle quality assurance inspector Patrick Adkins knows what it was like to see one of his spaceships return in pieces. Adkins remembered:

I ended up at dusk in San Augustine, Texas, where I was told there were materials. I entered the room and [astronaut] Chris Ferguson was seated at the end of the dimly lit room at a table sorting through bags of items. I introduced myself, and he showed me a closet where more materials were kept. I opened the door and was hit with the odor of oxidizer.

As I gloved up and sorted through the items, I found a CD with Hebrew writing on it. Not something you’d expect to find in the woods of east Texas. I found a wristwatch Velcro band. Both those items, as well as some distressed mission patches I assured cleanliness, I bagged them and gave them to Chris. As I sorted through it all, I found small items from the forward reaction control system as well as a number of other items of crew equipment. It was then I went over in my mind the enormity of the destruction and our task.

Adkins’ story, along with countless others who trudged through sometimes dangerous conditions during that winter and spring, is told at last in Bringing Columbia Home. I caught up with Jonathan Ward and discussed the arduous recovery efforts, and how a space shuttle and its diverse crew of seven brought whole communities together.

By March 11, 2003—less than a month after hangar operations began—nearly 34,000 pieces of debris were in the hangar, totaling 43,200 pounds, or roughly 19% of Columbia’s dry weight. (credit: NASA/KSC) |

There has been a lot of advance praise for your new book, co-authored with former space shuttle launch director Mike Leinbach, who was a leader in recovering the remnants of Columbia after its high-altitude hypersonic breakup on February 1, 2003. First of all, set the scene. What led to you both pursuing this story, especially when many of the details are still so emotionally raw and painful?

Jonathan Ward: This is very much Mike’s personal story. Mike was the launch director for the last third of the Shuttle program, including Columbia’s final mission. He was in charge of KSC’s “rapid response team” that would normally go to a trans-Atlantic landing site to try to recover the shuttle if there was an abort during launch. In this case, the team was deployed to Louisiana and Texas to assess the situation after Columbia disappeared. Less than two weeks later, Mike was pulled to run the reconstruction of Columbia’s debris in a hangar at KSC.

| When I interviewed people on that team and many of the astronauts who were involved, everyone I talked to said, “The real story is with the people in East Texas.” |

Mike and I met at the funeral of a mutual friend, Apollo and Shuttle launch test conductor Norm Carlson. We agreed to go have lunch together a few weeks later. At the end of our lunch, Mike said he wanted to write a book about Columbia, but didn’t have the time to see such a project through. I immediately knew in my gut that we needed to write this book. I believe that the loss of Columbia was NASA’s “forgotten” tragedy. Unless you worked for NASA, lived in East Texas, or closely follow the space program, chances are you don’t remember the Columbia accident. We agreed to a follow-up conversation a few weeks later. I was intrigued by Mike’s willingness to talk about the deeply human aspects of his challenges of leading people through an extremely tragic period while he himself was dealing with his own shock and grief. Within a couple of weeks, Mike had me talking to people like former NASA administrator Sean O’Keefe and other senior NASA officials.

Mike’s initial vision was to make this a book about the rapid response team and the reconstruction of Columbia’s debris. When I interviewed people on that team and many of the astronauts who were involved, everyone I talked to said, “The real story is with the people in East Texas.” Mike graciously agreed to expand the scope of the book. After I spent a week in East Texas interviewing some of the amazing everyday people who were involved in the recovery, we knew we had the “right” story.

Now we feel we have produced the first definitive look at the overall recovery and reconstruction of Columbia. It’s interesting to note that all the “officials” I interviewed who participated in the Columbia recovery have the same comment on reading the book: “I had no idea all of this was going on.” And every interviewee had this observation: This was a defining moment in their lives, no matter how small their individual roles were. People are deservedly proud of helping NASA and its people in its moment of direst need.

Without spoiling too much of the book, there are details within it that grab the reader, including the fact that, being a development vehicle, Columbia was outfitted with equipment other orbiters did not possess; undoubtedly this enriched the process of figuring out what happened during the orbiter’s final minutes. Also, some of the recovery was sometimes aided by simply fateful circumstances. What were things that struck you most about the flight and recovery that occurred almost by fate, or strange coincidence?

Ward: Columbia’s loss was the result of NASA’s luck running out on the orbiter’s ability to withstand impact from foam shed by the external fuel tank during ascent. There had been many, many previous incidents where the shuttle escaped from foam collisions relatively unscathed. NASA convinced itself that Columbia would make it home in one piece, just as the shuttles had so many times before. After the accident, NASA re-framed the situation. It wasn’t that Columbia had been the victim of an unlucky fluke—it was that the past crews had been very lucky that previous strikes weren’t worse.

| Had the accident occurred at the same point in the reentry profile one orbit later, the shuttle’s debris would have impacted downtown Houston. |

We dodged a number of bullets in Columbia’s breakup. The accident occurred with the orbiter traveling 12,000 mph (19,300 km/h) at an altitude of 200,000 feet (61,000 meters) and a few miles south of Dallas. Most of Columbia’s debris fell over a relatively sparsely populated area of East Texas. Its engine powerheads hit the ground near Ft. Polk, Louisiana while still traveling at Mach 2. Amazingly, no one on the ground was killed or injured by the 40 tons of material that fell from the sky over an area 250 miles (400 kilometers) long by 20 miles (32 kilometers) wide, and there was no major damage to structures on the ground. Also, had the breakup occurred just a few seconds later, several of the crew members would have likely been lost in Toledo Bend Reservoir or the Gulf of Mexico.

Had the accident occurred at the same point in the reentry profile one orbit later, the shuttle’s debris would have impacted downtown Houston. Public safety concerns prompted NASA to change subsequent reentries to an “ascending node” profile, so that the orbiter would approach the landing site from the southwest, over the Pacific or the Gulf of Mexico, rather than over the continental US.

It was also fortunate that Columbia came to Earth in an area where the local police and civic officials had been trained in the Incident Command System, which enabled officials in even the smallest towns to take control of the situation quickly. And, of course, this was an area where the local citizens felt it was their moral duty to take care of people in need. That extended from recovering the remains of Columbia’s crew with dignity and respect to treating the grieving NASA searchers like honored guests.

The story of the recovery of Columbia’s flight data recorder is of course the stuff of legend. The area where it was found had been searched twice before, but somehow the searchers missed the box sitting on a little rise in a clearing. While other boxes that had been in the avionics bay next to it had been found melted or badly damaged, the OEX recorder was in such pristine condition that the property tag could still be read easily. The tape inside had snapped when the orbiter broke up, but the data was readable up until the moment the vehicle lost power.

And finding the video of the first part of the crew’s reentry was a major stroke of luck. The video showed the astronauts on the flight deck happy, relaxed, in control, and enjoying their ride. It was obvious that they had no fear or any inkling that anything was wrong with their ship.

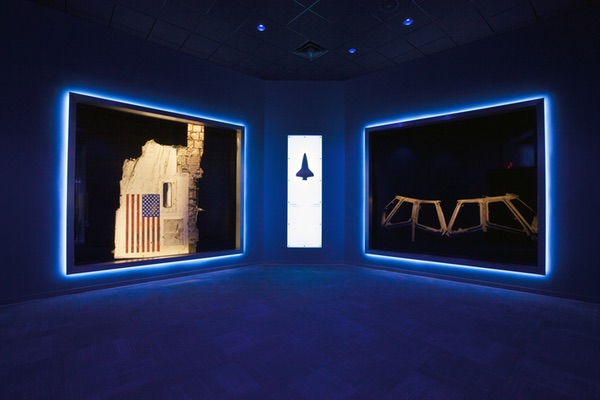

A section of the fuselage recovered from space shuttle Challenger, left, and the flight deck windows recovered from space shuttle Columbia are part of a new, permanent memorial, “Forever Remembered,” which opened June 27, 2015, in the Space Shuttle Atlantis exhibit at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex in Florida. (credit: NASA/Kim Shiflett) |

Of course, there is the human quality associated with the Columbia tragedy: seven astronauts were lost, and later, a helicopter crash during recovery efforts claimed several lives. How does a writer address these losses in a way that is tasteful and respectful, yet while still telling the (sometimes very unpleasant) objective truth about events? Did writing this affect you emotionally? (I am sure Leinbach was affected by recounting the story.) What were your thoughts first seeing the cockpit windows at Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex’s “Forever Remembered” exhibit?

Ward: I found it very difficult to keep from getting emotionally overwhelmed while researching and writing about such a tragic event—and I was only a “spectator.” I of course read the official reports and the crew survivability studies and heard things from the searchers that I would never dream of writing down. I had more than a few sleepless nights along the way.

Out of sensitivity to the families, we agreed very early on that we would not address anything about the crew that was not already public knowledge, and in fact we discussed less than has been published elsewhere. We agreed not to speculate on what was going on inside the shuttle. Astronaut Jim Wetherbee talked about his “8-8-8 rule” for how the crew recovery operations were to be handled: “Eight days from now, eight months from now, and eight years from now, we must be able to live with the consequences of the decisions that we will make. Every decision must be based on our highest judgment using our greatest professionalism and human values.” We felt that was a very appropriate standard to set for ourselves in telling this story. No sensationalism. The story was dramatic enough as it was.

It was of course tough for Mike to go through this process. One of the benefits of working with him over a long period of time is that even if he was willing to talk about something, it was occasionally hard for him to do it in the moment. We might come back to that topic the next day or even three months later and then be able to discuss it.

I have the deepest respect for Mike and everyone who was involved in this effort. Many of the searchers suffered from what is clearly PTSD. Many have still not recovered from the emotional scars from the loss of the shuttle and her crew. Many a grown man broke into tears during my interviews, and I am humbled that people felt comfortable enough talking with me to let those feelings emerge after so many years.

| I do feel we told the story with dignity and respect, and I sincerely hope that the book will be a fitting tribute to them and all that they stood for. |

Regarding “Forever Remembered”: Early in the research phase for the book, Mike arranged for me to tour the room in the VAB where Columbia’s debris is stored and where representative pieces are on display. He felt it was important for me to experience Columbia firsthand. This was a few months before the Forever Remembered exhibit opened. Even having been through the preservation room and seeing photos of Columbia’s window frames in the reconstruction hangar in 2003, I was unprepared for how powerfully those windows would affect me in person. I’ve been by there many times now and I’m still overwhelmed. From the effects of oxidation to the broken silicon window shards to the bits of grass and Texas mud still embedded in them, there’s nothing more powerful you could possibly say than what those windows tell you themselves.

In early November this year, after the book was completely finished, I went back to Forever Remembered one morning and found that I had the place entirely to myself. I stared long and hard at those windows, this time trying to picture Columbia’s crew happily going about their tasks on the other side. And then I found myself wondering: if I stood face to face with Rick, Willie, Mike, KC, Laurel, Dave, and Ilan, could I look them in the eye and tell them that I did my absolute best to honor them with this book? That’s a tough question to answer. I do feel we told the story with dignity and respect, and I sincerely hope that the book will be a fitting tribute to them and all that they stood for.