And the sky full of stars: American signals intelligence satellites and the Vietnam Warby Dwayne A. Day

|

| What has only been recently declassified is that soon after this complicated and highly sensitive operation was underway, American intelligence officials scrambled to task the nation’s fleet of top secret signals intelligence satellites with monitoring how the Soviet Union would respond. |

A flight of North Vietnamese MiGs headed out to intercept the planes until a Talos long-range missile from the cruiser USS Chicago blew one out of the air and the MiGs retreated. The American planes dropped their mines—long, blunt-nosed cylinders—along the access channel to Haiphong Harbor, North Vietnam’s major port, at precisely 0859 local time, just minutes before President Richard Nixon appeared on national television in the United States to deliver a speech announcing the operation. The president spoke extra slowly to give the American aircraft time to depart the area before he revealed the full extent of the mining operation.

What has only been recently declassified is that soon after this complicated and highly sensitive operation was underway, American intelligence officials scrambled to task the nation’s fleet of top secret signals intelligence satellites with monitoring how the Soviet Union would respond. In particular, they wanted to track Soviet ships in the area, apparently to determine if any of them were damaged by the American mines, which could have derailed sensitive arms control negotiations then underway.

An A-7 Corsair of VA-22 loaded with Mk-52 mines on USS Coral Sea, 1972. (credit: Fotis Dee, US Navy) |

A long bloody war

By 1972 the United States had been militarily involved in Vietnam for over a decade. The war had become the quagmire that many people had feared. But for several years the United States had engaged in a policy of “Vietnamization,” a euphemism for military withdrawal from South Vietnam. With the vast majority of American troops gone, the North Vietnamese invaded in late March 1972 in an action that became labeled “the Easter Offensive.” President Nixon ordered a counterattack in the form of a B-52 bombing campaign known as Operation Linebacker, and then the mining of North Vietnam’s only major port, Haiphong.

The mining of Haiphong Harbor, known as Operation Pocket Money, had been studied numerous times throughout the war as a means of cutting off North Vietnam’s supply of weapons—particularly SA-2 surface-to-air missiles, delivered by Soviet merchant ships. But it was not until May 5 that the Commander in Chief of the US Navy’s Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC), Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, began actively planning the mining operation. Soon after it was underway, Zumwalt contacted the secretive National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) about using its fleet of low Earth orbit electronic intelligence (ELINT) satellites to monitor the Soviet maritime response to the mining.

According to a newly declassified memo written in early December 1972 by Brigadier General David Bradburn to NRO Director John McLucas, when President Nixon announced the action, “there was a flurry of messages and phone calls in the middle of the night which resulted in a redirection of all our ELINT satellites to try and ascertain any Soviet reaction to our mining of North Vietnam.” Bradburn headed the NRO’s executive staff in Washington, DC, and although the word “Soviet” is deleted from Bradburn’s memo, other historical accounts of the mining operation indicate that there were 16 Soviet ships in the harbor during the mining. The United States was involved in delicate Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty discussions at that time and had even delivered a private communication to the Soviets about the mining operation shortly before it began. The mines were set with a 72-hour time delay, after which they would become armed. Presumably, one of the goals of the satellite monitoring was to determine if any Soviet ships had struck a mine trying to leave the harbor too late.

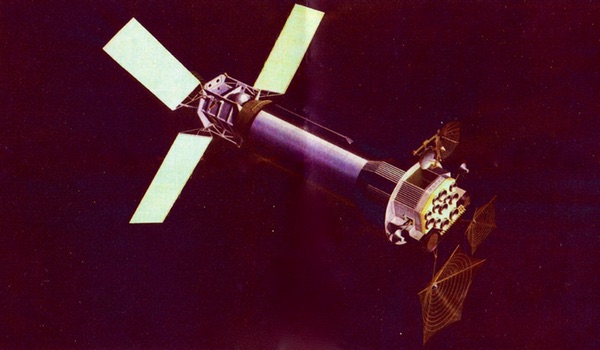

The NRO then had several satellites performing the electronic intelligence mission in low Earth orbit. ELINT is a subset of signals intelligence, or SIGINT, and is primarily focused upon detecting radars and other emissions from ground equipment. The satellites included STRAWMAN 4, a seven-meter-long barrel-shaped spacecraft sprouting a nest of Earth-pointing antennas at one end and three extendable solar panels at the other. There were also two much smaller satellites: an oblong ball approximately one meter in diameter covered with solar cells, known as POPPY, and TRIPOS/SOUSEA, a small box-like satellite approximately one meter on a side, with several aerials sticking out of its sides. At the time the satellites may also have had the capability to detect radio emissions from surface vessels and other emitters, although many of their capabilities remain classified to this day. The satellites were also equipped to do more than simply detect the emissions. They could locate their source and record technical characteristics about the signals.

| The satellites were also equipped to do more than simply detect the emissions. They could locate their source and record technical characteristics about the signals. |

The NRO and the National Security Agency had, in fact, been working for over a year to make the satellites more responsive to the Navy. This had involved both fleet exercises and changes in procedures, so the request to use the top-secret satellites to monitor a major military operation was something that NRO officials were ready for. The Haiphong monitoring request was made by Admiral Zumwalt and routed through the SIGINT Overhead Reconnaissance Subcommittee, or SORS. According to Bradburn, the intelligence community had improved the procedures for starting up a special collection effort involving SIGINT satellites. Before 1972, a SORS telephone vote was required to use the satellites for special operations, but now NRO and NSA could react to requests from any SORS member, subject to further confirmation. Bradburn wrote that the Navy was pleased with the quick response and “it illustrates that at least one of our ‘customers’ appreciates our collection efforts.”

John Darrell Sherwood, in his 1999 book Fast Movers: Jet Pilots and the Vietnam Experience, explained how complex and rushed the Haiphong mining operation was. Aviators on the USS Coral Sea planned the mission using an old French map of the harbor. They determined that they would have to drop the mines with great precision, and that they would have to fly at very low level to avoid enemy air defenses. The A-6 Intruders carried mines that weighed twice as much as those carried by the A-7 Corsairs, and without their nosecones they were very draggy and slowed down the planes. The bigger mines would detect the magnetic signature of a passing ship, whereas the smaller ones would listen for their acoustic signatures. During planning for the mission, the commanders decided to declare any aircraft in the area above 1,000 feet as hostile. But the leader of the mission told his superiors, “I want anything above five hundred feet to be declared as hostile. We’ll be well below that.” He knew that the MiGs would come down for them, “because when you’re sitting there with eight thousand pounds of mines without cones on them, you’re just a sitting duck.”

The goal of the satellite SIGINT collection effort was to provide insight into how Soviet ships reacted to the mining. Of the 16 Soviet ships and 21 other vessels in the harbor, four Soviet and one British ship managed to depart before the mines became active. The rest of the ships were stuck in the harbor until the war ended in January 1973 and the mines were removed. The NRO satellites had detected vessels in the reporting area prior to the May 9 mining operation. But the number of detections increased substantially during the six-week period after the mining operation, which Bradburn attributed both to an increase in maritime activity and turning on the satellites over wider areas. Bradburn did not indicate what type of ships were detected and what they were doing in the area.

Big Black goes to war

Bradburn’s memo to McLucas was prepared after the fact as part of a briefing package for the NRO Director to talk about the NRO’s contributions to tactical forces, an intelligence mission that was relatively new for the NRO. The very first reconnaissance satellites started in the mid-1950s had been intended to assist Strategic Air Command in its mission of waging nuclear war against the Soviet Union, but by the early 1960s American intelligence satellites were focused almost exclusively on gathering intelligence for strategic planning purposes. Intelligence agencies used the satellites, which eventually became known as “national assets,” for determining how many missiles and bombers America needed, and where to target ICBMs. The satellites did not get used by tactical forces, both because their data could not easily be relayed to field units, and because the satellites and their products were so secret—“black”—that field commanders were not allowed to know they even existed.

| The use of satellites to detect ships at sea was something that the NRO had been evaluating for several years. But in the early 1970s none of the signals intelligence satellites in orbit had been designed for this mission. |

By the later 1960s, with the Vietnam War in full swing, the NRO had apparently begun feeling pressure to make its satellites more immediately relevant to the military, particularly with the war in Southeast Asia consuming so many other resources and attention. In 1968 the NRO began using a STRAWMAN satellite as part of a program called PENDULUM for reporting radar targets in North Vietnam, such as the SA-2 surface-to-air missile sites that could shoot down American aircraft. According to Bradburn, after passing over the target area, “perhaps 45 minutes or a little over two hours later depending on whether it was on the satellite’s exact path, it passed over our tracking station at Vandenberg and the information was read-out by command. The information was sent immediately by microwave to the Satellite Tracking Center in Sunnyvale and immediately relayed to our special computer facility.” Bradburn further explained that “after some computer processing, the messages describing North Vietnamese radar locations and operating characteristics were sent to SAC and (via NSA) to Seventh Air Force at Ton Son Nhut.” Bradburn explained that despite this roundabout way of delivering intelligence information to Vietnam, “the time from observation of North Vietnam to arrival of the finished information at Ton Son Nhut varied from three to eight hours. This is highly competitive with the time it takes to get the same kind of information from airplanes flying in the theater of operations.”

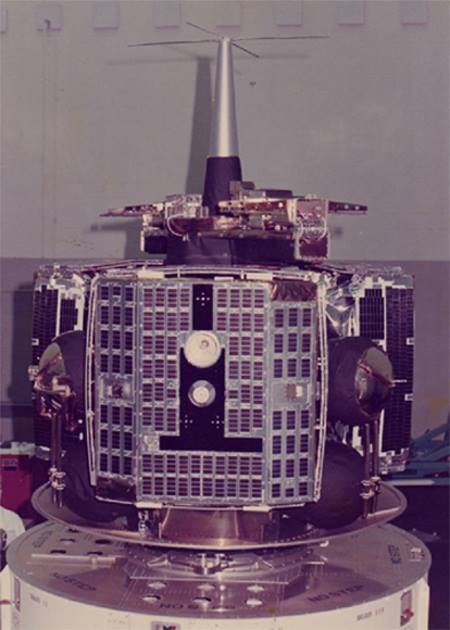

Three PARCAE ocean surveillance satellites attached to their dispenser satellite at the Naval Research Laboratory. PARCAE entered service in the late 1970s with the mission of tracking Soviet ships at sea. |

Big Black goes to sea

The use of satellites to detect ships at sea was something that the NRO had been evaluating for several years ever since POPPY satellites had detected radar emissions from naval vessels in the later 1960s. In 1970 the Chief of Naval Operations ordered a study of overall ocean surveillance requirements and the Naval Research Laboratory—which designed the POPPY satellites—responded by producing the Ocean Surveillance Requirements Study, a comprehensive five-volume report. Eventually, by the mid-1970s, the NRO would launch a series of satellites known as PARCAE expressly designed to track Soviet ships at sea (see “Above the clouds: the White Cloud ocean surveillance satellites”, The Space Review, April 13, 2009). But in the early 1970s none of the signals intelligence satellites in orbit had been designed for this mission.

By 1971, the NRO had teamed up to provide data on the position of ships at sea to the US Navy. That year the NRO engaged in two exercises with the Navy named TANGIBLE and ROPEVAL. During TANGIBLE, which took place in the spring, NRO satellites had tried to detect Navy ships operating off the coast of San Diego. But TANGIBLE was apparently a disappointing test. Navy captains had not kept good logs of their locations and what electronic signals they were emitting, so they could not be well correlated with signals detected by the secret satellites flying overhead. ROPEVAL was a fall 1971 exercise that extended from Midway Island all the way to the US West Coast, and naval commanders were required to be much more diligent at recording information that could be compared to the satellite data. During the summer of 1971, the same satellites had been used as part of Operation TACTFUL, to monitor a Soviet naval operation and provide data on their positions at sea to the US Navy “as expeditiously as possible.” Later that year, the NRO had also proposed to the NSA that they streamline their lines of communication so that the data could be provided directly to the Navy rather than first going through an NSA processing center outside Washington, DC.

In his memo, Bradburn also mentioned Project FLAVOR, which he referred to as the oldest collection project involving American ELINT satellites then underway, stating that FLAVOR “has produced some of the key information about Soviet air-to-surface missile radars…” In other words, American satellites in low Earth orbit were able to collect radar signals from Soviet missiles fired from aircraft far below, and most likely aimed at target ships. Such data could be valuable to the US Navy for developing countermeasures to those missiles.

| The Haiphong satellite operation may not have been a watershed event in the development of the use of satellites in ocean surveillance, but it demonstrated that top secret satellites designed for detecting Soviet radars in Europe and Asia could perform similar tasks over the ocean. |

Bradburn clearly considered the post-Haiphong monitoring operation to be a success, although it is not known how the intelligence information was used and how it benefitted decision makers. The US Navy later removed the mines from the harbor as part of a negotiated settlement, although the Soviet navy certainly would have wanted to acquire some of them, and knowing if Soviet minesweepers were heading toward Haiphong would have been of interest to American intelligence analysts and to the senior Nixon administration officials who wanted to keep Haiphong’s harbor closed.

After the successful use of the satellites, the NRO-Navy relationship continued. In December 1972, the US Intelligence Board gave the NRO and NSA new “Special Mission Guidance” recommending that POPPY, STRAWMAN 4, and a new satellite launched in July named URSALA 1, “provide coverage of Soviet shipborne emitters in the Sea of Japan for time critical reporting during the period 7 December through 30 January 1973.” They were requesting that the data be relayed to CINCPAC and the U.S. Commander of Naval Forces, Japan within six hours after a satellite collected it.

The Haiphong satellite operation may not have been a watershed event in the development of the use of satellites in ocean surveillance, but it demonstrated that top secret satellites designed for detecting Soviet radars in Europe and Asia could perform similar tasks over the ocean. Only a few years later, this would become a full-time mission for the National Reconnaissance Office.