Will WFIRST last?by Jeff Foust

|

| “Given competing priorities at NASA, and budget constraints, developing another large space telescope immediately after completing the $8.8 billion James Webb Space Telescope is not a priority for the Administration,” the document stated. |

There was some déjà vu in the proposal as well. The budget calls for cancelling the same five Earth science missions the fiscal year 2018 budget proposal sought to cancel. (One of those projects, the Radiation Budget Instrument, had already been canceled by NASA last month because of cost and technical issues.) The budget also again plans to close NASA’s Office of Education, a proposal in last year’s budget request that was quickly shot down by members of both parties in the House and Senate.

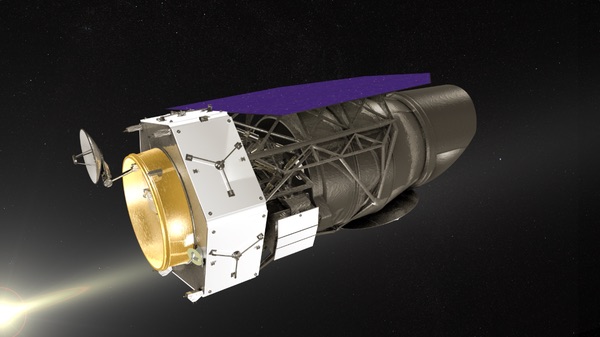

The budget, though, included one surprise: it sought to cancel the Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST). The mission, still in the early phases of development, is the next large, or “flagship,” mission in NASA’s astrophysics program, which planned to launch in the mid-2020s. WFIRST, the top priority flagship mission in the 2010 astrophysics decadal survey that prioritized space- and ground-based projects for the next decade, offered to give astronomers the ability to achieve major discoveries in topics from dark energy to exoplanets.

A document released by the Office of Management and Budget, outlining major cancellations and cutbacks across the federal budget, was blunt when it came to WFIRST. “Given competing priorities at NASA, and budget constraints, developing another large space telescope immediately after completing the $8.8 billion James Webb Space Telescope is not a priority for the Administration,” the document stated, noting that WFIRST would cost more than $3 billion.

Those competing priorities include NASA’s exploration plans, such as capabilities to support missions to the Moon to implement the administration’s Space Policy Directive One, signed by President Trump in December (see “Where, but not how or when”, The Space Review, December 18, 2017). The budget included plans for a series of commercially-developed lunar missions, including one that could launch as soon as 2019, as well as development of the Deep Space Gateway, now called the Lunar Orbiting Platform - Gateway.

The cancellation of WFIRST was almost an afterthought in the “State of NASA” address by NASA acting administrator Robert Lightfoot. “We did have to make some hard decisions in science,” he said in the speech at the Marshall Space Flight Center. “This budget proposes cancelling our WFIRST mission and taking those resources and redirecting them to other agency priorities.”

Andrew Hunter, the agency’s acting chief financial officer, said that the agency needed to reprogram the large “wedge” of funding planned for WFIRST in future years, known as “out-years” in budget jargon, given projections of flat overall spending for NASA beyond 2019. The mission, which received $105 million in 2017, was on track to receive $302 million in 2019 and more than $400 million per year in 2020 through 2022, according to the agency’s 2018 budget proposal (Congress has yet to complete a final 2018 spending bill, more than four and a half months into the fiscal year, but NASA requested $126.6 million for WFIRST in 2018.)

“When you’ve got a large flagship mission like that, you’ve got a large out-year wedge,” he said. “With the budget staying flat in the out-years, we’re trying to show some growth in the exploration activities of the agency in the out-years.”

Hunter estimated that $128 million of WFIRST funding planned for 2019 would remain in NASA’s astrophysics program or other parts of the Science Mission Directorate. The full budget proposal document, released February 14, noted increased funding for astrophysics research programs. Some of that increase goes to a new “directed research and technology” line item that “funds the civil service staff that will work on emerging Astrophysics projects, instruments, and research.” That staff includes people who would have been working on WFIRST.

Other funding could go to smaller, competed missions. The budget proposes a significant increase to the Astrophysics Explorer program, which funds smaller missions that are competitively selected. The “future missions” budget line there would increase from $15 million in 2017 to $112 million in 2019, growing to nearly $400 million in 2023. That would allow the program to consider a “probe-class” mission, a concept for a larger, but still competitively-selected mission with a cost of up to $1 billion.

| “We think that the science that WFIRST is going to do is terrific,” said Hewitt. “But then there are the ‘howevers.’” |

That proposed spending increase on research and smaller missions has not allayed astronomers. “We cannot accept termination of WFIRST, which was the highest-priority space-astronomy mission in the most recent decadal survey,” said Megan Donahue, a Michigan State University astronomer and president-elect of the American Astronomical Society (AAS), in a February 14 statement by the organization. She warned that an overall 10 percent spending cut for NASA astrophysics included in the budget projections “will cripple US astronomy.”

“Not only is WFIRST a top decadal-survey priority in astronomy and astrophysics, but the mission has also undergone rigorous community, agency, and Congressional assessment and oversight and meets the high expectations of an astrophysics flagship,” added Kevin Marvel, AAS executive officer, in the statement.

Growth of capabilities, and of costs

WFIRST has not been without its problems. Since its selection as the top-priority flagship mission in the 2010 decadal, the mission has evolved significantly. The biggest change was the decision by NASA to use one of two 2.4-meter telescope assemblies donated to NASA by another government agency (widely believed to be, but never formally identified as, the National Reconnaissance Office.) The mirror is much larger than the one originally planned for WFIRST, increasing its scientific capabilities. But adapting the mirror for use on WFIRST would require a significant amount of work, even with the apparent cost savings of using an already-built telescope.

NASA also sought to add another instrument to WFIRST, a coronagraph. That instrument, able to block the light of individual stars, would enable direct observations of exoplanets orbiting those stars. There was, though, the expense of developing the coronagraph technology and adding the instrument to the mission.

The result was a mission that was more capable, but also more expensive, than originally envisioned when the National Academies committee that worked on the decadal survey completed its report in 2010. “NASA has worked closely with the Academy” on the changes with WFIRST, said David Spergel, an astrophysicist with Princeton University and the Flatiron Institute who co-chairs the WFIRST science team and is a previous chairman of the Space Studies Board of the National Academies.

Spergel, speaking during a panel discussion about WFIRST at the 231st meeting of the AAS January 12 in suburban Washington DC, offered a one-sentence summary of those discussions: “This looks good, but make sure this doesn’t imperil the broader program.”

An example of those discussions was a midterm review of the astrophysics decadal completed in 2016. “We think that the science that WFIRST is going to do is terrific. It’s an incredibly exciting mission, and it will take NASA into the next decade with a very capable instrument,” said Jacqueline Hewitt, a professor of physics at MIT who chaired that midterm assessment, during that panel discussion. “But then there are the ‘howevers.’”

Among those “howevers” was the growing cost of WFIRST. “I, for one, was quite surprised that the WFIRST that appeared before this committee was very different from the one that was proposed by Astro2010,” she said of the discussion of WFIRST by her committee. “WFIRST took a lot of our time just getting our heads around how this mission would respond to the science, what all these changes would actually mean.”

Hewitt said that the committee ultimately supported that revised WFIRST, but had a concern about its growing cost. “Between the time that we finished drafting our report and we actually submitted it, we noted the costs had gone up another $550 million,” she said, larger than the cost of some small astrophysics missions. “In units of Explorers, that’s about 1.5. So, there was a bit of a concern there.”

The report recommended that NASA perform an independent assessment of WFIRST before proceeding with its development. NASA agreed, deciding to postpone moving WFIRST into the next phase of development while convening the WFIRST Independent External Technical/Management/Cost Review (WIETR). Its report, delivered to NASA last fall, warned of significant cost growth with the mission: a cost of at least $3.6 billion, and more likely $3.9 billion, versus a previous estimate of $3.2 billion (see “More problems for big space telescopes”, The Space Review, October 30, 2017).

“The bottom line is that the current scope and complexity don’t fit with the anticipated available funds,” said Peter Michelson, one of the WIETR co-chairs, at a meeting of the Committee on Astronomy and Astrophysics October 25.

| “We cannot allow unbudgeted costs to occur on WFIRST the same way if did on James Webb,” Smith said. “The impact to other science missions, as well as other activities at NASA, would be too great.” |

The detailed report, released a month later, blamed the decisions on using the 2.4-meter telescope and adding the coronagraph for the cost growth in WFIRST. “After multiple discussions that set the boundary conditions, NASA HQ made a series of decisions that set the stage for an approach and mission system concept that is more complex than probably anticipated from the point of view of scope, complexity, and the concomitant risks of implementation,” the report stated.

The report also noted that the cost growth on WFIRST would put pressure on other, smaller astrophysics programs. “NASA HQ should be cognizant of community sensitivity regarding the perceived large and growing opportunity cost of WFIRST, relative to other compelling priorities for [NASA’s Science Mission Directorate], including other strategic missions,” it stated.

NASA responded to modifying WFIRST in an effort to reduce its costs back to $3.2 billion. The coronagraph would now be considered as a technology demonstration rather than a full-fledged science instrument, with the cost of its development shared with NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate.

“The fundamental architecture of the coronagraph instrument as not changed,” said Jeremy Kasdin, a Princeton University professor who leads the coronagraph team, said during a session on WFIRST at the AAS meeting January 10. “Most of the savings here are coming from not testing certain modes and not integrating certain modes.”

Thomas Zurbuchen, the NASA associate administrator for science, directed that change in the coronagraph instrument in an October memo, as well as other studies of ways to reduce costs of the mission. That work was due to be completed this month.

Wanted: a champion of astrophysics

Nowhere during those discussions was there any thought to canceling WFIRST outright. Zurbuchen, in his memo directing the cost-reduction effort, warned that if that effort could not get the mission’s cost back down to $3.2 billion, “I will direct a follow-on study of a WFIRST mission consistent with the architecture described by the Decadal Survey.” That would involve dumping the 2.4-meter donated telescope for a smaller one originally proposed for the mission.

WFIRST was discussed at a December 6 hearing by the House Science Committee’s space subcommittee, which also discussed delays in the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope and work on other missions. “WFIRST is a critical new flagship mission, and we need to make sure that it stays on course,” said Rep. Brian Babin (R-TX), chairman of the subcommittee. “The program needs reasonable timelines and a realistic budget.”

The chairman of the full committee, Rep. Lamar Smith (R-TX), sounded more concerned about WFIRST. “We cannot allow unbudgeted costs to occur on WFIRST the same way if did on James Webb,” he said. “The impact to other science missions, as well as other activities at NASA, would be too great.”

| “US is abandoning its leadership in space astronomy,” Spergel said. “Abandoning WFIRST is abandoning US leadership in dark energy and exoplanets.” |

One of the witnesses at that hearing was Tom Young, a former director of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and former president of Martin Marietta. Young is not one to mince words at congressional hearings or other committee meetings, but at the December hearing did not sound alarmed about the cost growth in WFIRST and NASA’s reaction to it.

“NASA is to be congratulated for taking an important step with the establishment of the WFIRST Independent External Technical/Management/Cost Review,” he said. “I want to emphasize that there is no cause for panic. What is transpiring is a perfectly healthy process to assure that the scope, cost, and risk are appropriately defined prior to proceeding past Milestone B.” That milestone, known as Key Decision Point (KDP) B, was delayed by NASA to perform the independent review and the subsequent cost-reduction effort.

There was no sign at that hearing that members thought cancelling WFIRST was on the table. At last month’s AAS meeting, the focus was on the outcome of those cost-reduction efforts and moving ahead with the mission’s development, with optimism that the revised mission could fit in that $3.2 billion cost.

“All these [changes] taken together, the project assesses gets it within $3.2 billion,” said Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s astrophysics division, said at a town hall meeting at the conference January 10. That would be confirmed by an independent review, followed by passing through KDP-B in March or April.

Given that status, with the review of reducing WFIRST’s costs ongoing, the astronomy community was taken by surprise by the decision to cancel the mission. “US is abandoning its leadership in space astronomy,” Spergel tweeted immediately after the release of the budget. “Abandoning WFIRST is abandoning US leadership in dark energy and exoplanets.”

The budget proposal is, as always, just that: a proposal that Congress will amend, if not toss out entirely. Key members of Congress didn’t directly address the proposed cancellation of WFIRST, but did express skepticism about other parts of the NASA budget. “The administration’s budget for NASA is a nonstarter,” said Sen. Bill Nelson (D-FL), ranking member of the Senate Commerce Committee, in a statement February 12.

Many astronomers are worried that the cancellation of WFIRST, if upheld, would damage the process by which astronomers develop priorities for missions through the decadal process that guide investments by NASA.

“These efforts to achieve community consensus on research priorities are vital to ensuring the maximum return on public and private investments in the astronomical sciences,” Marvel said in the AAS statement. “The cancellation of WFIRST would set a dangerous precedent and severely weaken a decadal-survey process that has established collective scientific priorities for a world-leading program for a half century.”

| “As those trades are made, going from amongst scientific disciplines all the way up to discretionary versus mandatory funding, you need somebody at the table who actually cares about astronomy and astrophysics,” Hammond said. |

But this is not the first time in recent memory that an administration has put a major astrophysics mission on the chopping block. Four years ago, the Obama Administration proposed cancelling the Stratospheric Observatory For Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), a converted Boeing 747 that holds a 2.5-meter telescope. That decision came after SOFIA, after many years of development, and endorsements by past decadal surveys, was about to enter regular operations (see “Aborted takeoff”, The Space Review, March 17, 2014).

As with WFIRST, administration officials said the cost of SOFIA was unaffordable given other priorities. “[T]he Budget sharply reduces funds for the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy in order to fund higher priority science missions,” the Office of Management and Budget said of the proposed cut to SOFIA.

“We had to make choices,” Charles Bolden, NASA administrator at the time, said. “SOFIA has earned its way, it has done very well, but I had to make a choice, and that choice was that we would focus on those other efforts.”

However, astronomers, and members of Congress, pushed against the cuts. A few months later, the effort to kill SOFIA was dead, and the airborne observatory continues to operate to this day.

Astronomers hope that the same will happen with WFIRST. “We look forward to working with Congress to restore funding for WFIRST and for NASA astrophysics overall,” Donahue said in the AAS statement.

Those advocates will need allies within Congress. At the WFIRST panel at last month’s AAS conference, Tom Hammond, a member of the House Science Committee staff speaking for himself, noted JWST had Sen. Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) as a staunch supporter for the telescope despite its problems. Rep. Smith, he added, has backed astronomy missions. However, Mikulski retired from the Senate after the 2016 elections, and Smith announced plans last fall to retire after this November’s elections.

“It’s important that the community find a champion going forward,” Hammond said. “One of my unsolicited recommendations is for the community to reach out and try to find an advocate, a champion going forward. As those trades are made, going from amongst scientific disciplines all the way up to discretionary versus mandatory funding, you need somebody at the table who actually cares about astronomy and astrophysics.”

And, even if there is sufficient support in Congress to restore funding for WFIRST this time, there will be a next time, either for this mission or future major space science missions.