The end of an era in the exploration of Europaby Jason Callahan

|

| While many OPAG attendees seemed to be largely in favor of the mission, a few lone voices warned that the mission did not have broad-based support, either within the rest of the science community or politically. On November 6, Culberson lost his bid for re-election, and those lone voices seem much more prophetic. |

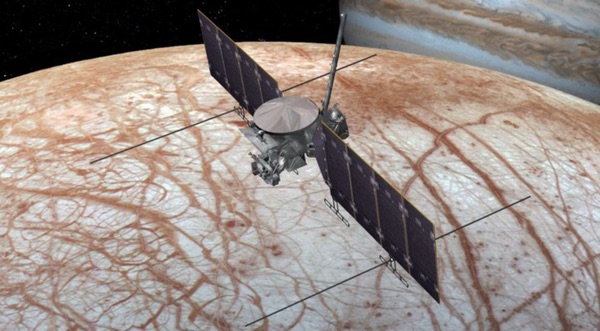

NASA is currently developing the Europa Clipper spacecraft that will orbit Jupiter and perform numerous swingbys of the icy moon. A version of that mission was prioritized in both the 2001 and 2011 planetary decadal surveys, but it likely wouldn’t exist if not for Culberson. As chairman of the Commerce, Justice, and Science (CJS) Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee, Culberson pushed back against the Obama Administration’s Office of Management and Budget, adding money to the budget for a Europa mission to begin development (commonly referred to as a “new start”) that wasn’t included in NASA’s budget request. NASA was essentially caught in the middle of the executive and legislative branches. Culberson was persistent, and eventually OMB approved the start of the mission, which should enter its confirmation phase early next year. Culberson then added language to budget bills calling for a Europa lander as well.

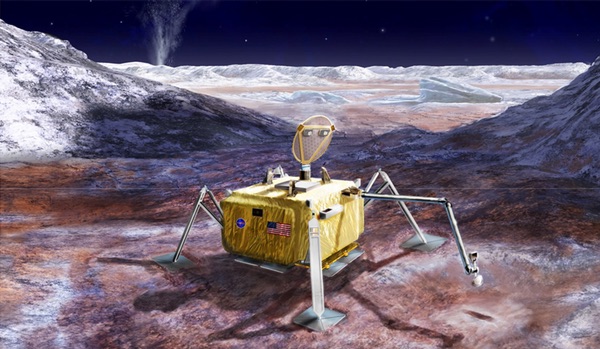

One concept for a Europa lander spacecraft, whose future is now threatened by the departure of Culberson. (credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech) |

A brief budget history of the Europa orbiter and lander

John Culberson assumed the chairmanship of the House CJS committee in 2014 and wasted no time in pushing NASA toward Europa. In the fiscal year (FY) 2014 Consolidated Appropriations Act, Culberson included $80 million “for pre-formulation and/or formulation activities for a mission that meets the science goals outlined for the Jupiter Europa mission in the most recent planetary science decadal survey.” NASA had not requested any funds for a Europa mission, though the agency was funding studies on what such a mission might look like.

The following year, Culberson included $100 million in the FY 2015 Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act (also called the “CRomnibus”) using the same language as the FY14 appropriation. NASA had asked for $15 million in its budget request for “pre-formulation work on the architecture for a potential Europa mission.”

In FY 2016, NASA requested $30 million to begin formulation activities on a Jupiter Europa mission. Instead, Culberson included $175 million in the FY16 omnibus spending bill for a Europa orbiter with a lander, and stipulated that the mission would be flown in 2022 atop NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS), a vehicle still under development.

In FY 2017, Culberson increased funding for Europa to $275 million and included language in the new omnibus spending bill instructing NASA to fly the orbiter and lander separately, in 2022 and 2024, respectively. NASA had requested only $49.6 million in FY17 for the Europa multiple flyby mission and nothing for a lander mission. Furthermore, NASA’s budget request stated that the mission would likely launch “in the late 2020s,” and the cost estimates included an Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) rather than an SLS, as the costs for an SLS were still unknown. The request did include a number allowing for an accelerated 2022 launch: $194 million for FY17.

| This funding trajectory is quite remarkable. It is rare that Congress provides money for science activities beyond what the community has requested. |

In the most recent omnibus, the FY 2018 Consolidated Appropriations Act, Culberson included $595 million for the orbiter and lander missions, insisting on the use of SLS launch vehicles for both, and adhering to the 2022 and 2024 launch dates. NASA requested only $425 million for the Europa Clipper mission with a later launch date, and nothing for the lander mission. The budget request specifically states that the planetary science decadal survey did not recommend a lander mission at Europa. Again, the request included a number for meeting the 2022 launch mandate. It was the same as the FY18 request, but costs increased dramatically in the following four years compared to the projections for a mission with a later launch date.

NASA’s FY 2019 budget request included $264.7 million for Europa Clipper and stipulated a 2025 launch date aboard an EELV. Again, there was no request for a Europa lander, and the FY19 number included to achieve a 2022 launch date for Clipper was $565 million. The House passed a CJS appropriations bill this year for FY 2019, though the Senate did not. In the House bill, Culberson included $545 million for Europa Clipper and $195 million for the lander. The bill’s language erroneously cited the 2011 decadal survey as recommending a lander to meet science goals at Europa.

| Fiscal Year | NASA Request | Appropriation |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 | $0 | $80 |

| 2015 | $15 | $100 |

| 2016 | $30 | $175 |

| 2017 | $50 | $275 |

| 2018 | $425 | $595 |

| 2019 | $265 | $740 (House bill) |

Several sections of the FY19 budget—including CJS—are currently under a continuing resolution until December 7. Given that the Democratic party won back the majority in the recent elections, Republicans will likely be keen to pass the remaining budget items before the start of the new Congress in January. It isn’t clear if the President will sign a budget without money for a wall along the Mexican border, and it is not likely that Republicans can pass a budget bill without Democratic support. As a result, the final FY19 funding for Europa remains in flux.

Nevertheless, this funding trajectory is quite remarkable. It is rare that Congress provides money for science activities beyond what the community has requested. To have a congressional champion for a project with no direct ties to his district is even more extraordinary. It is unfortunate that more members of Congress aren’t willing to support programs they view as being in the national interest even if they are not necessarily within a parochial interest. It is also worth noting that Culberson appropriated funds for Europa in addition to funds for all the other activities recommended in the decadal survey. That is, Europa did not generally come at the expense of other planetary science priorities. But some difficulties arose from his largesse.

Alternative designs for a Europa lander (credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech) |

Why an orbiter? Why a lander? Why now?

Culberson’s support for a Europa lander presented a problem for NASA. Europa orbiters have been discussed and studied within the American planetary science community since the 1990s, but a lander is a more recent proposal without such a pedigree. Although it has a core group of fervent supporters and is gaining interest from a broader audience, the lander mission has not been discussed at length by the overall planetary science community.

| Those recommendations resulted from the committee’s concern that a large flagship-class mission like Clipper could experience cost overruns that could impact the rest of the planetary science budget. |

In August, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine produced a new report that touched on that issue. Titled “Visions into Voyages for Planetary Sciences in the Decade 2013–2022: A Midterm Review,” (a clever twist on the decadal survey title Visions and Voyages for Planetary Science) the report is a midterm assessment of NASA’s progress at achieving the goals established by the decadal survey. Like the decadal survey, the report is mandated by law. The report found that NASA's planetary science program has made excellent progress at meeting most of the goals established in the decadal survey. It appears to be a very well-run program.

The report made a couple of recommendations regarding Europa Clipper:

Recommendation: NASA should continue to closely monitor the cost and schedule associated with the Europa Clipper to ensure that it remains executable within the approved life cycle cost (LCC) range approved at Key Decision Point-B (KDP-B) without impacting other missions and priorities as defined by the decision rules in Vision and Voyages (p. 36). If the LCC exceeds this range, NASA should de-scope the mission in order to remain consistent with the Vision and Voyages decision rules.

Recommendation: NASA’s Planetary Science Division [PSD] should implement an Independent Cost and Risk Review Process at Mission Definition/System Definition Review (Key Decision Point-B, or KDP-B) specifically for large planetary flagship missions to ensure that potential mission costs and cost risks are understood. (Chapter 3)

Those recommendations resulted from the committee’s concern that a large flagship-class mission like Clipper could experience cost overruns that could impact the rest of the planetary science budget. In this regard the committee had only to look at the astrophysics program, where cost overruns on the James Webb Space Telescope earned it the nickname “the telescope that ate astronomy.” But the planetary science community also remembers how the Mars Science Laboratory—now known as the Curiosity rover—vastly exceeded its cost and schedule baselines, sucking up money that could have been used for other Mars missions.

The committee had a recommendation for the Europa lander as well:

Recommendation: As a prospective flagship mission, the results of the NASA Europa lander studies should be evaluated and prioritized within the overall PSD program balance in the next decadal survey.

Supporting this recommendation, the committee wrote: “A lander was not prioritized or discussed in detail in Vision and Voyages, where it was referred to as a ‘far term’ mission. It also did not undergo a cost and technical evaluation like other large missions prioritized in the decadal survey. Given its cost and its potential impact on the rest of the planetary science program, the committee concluded that the mission should be vetted within the decadal survey process.”

Although not as strong as saying “don’t do the lander mission now,” it was clear that the committee believed that the lander mission needed much broader scientific support, which could really only come from the decadal survey. Without that support, the mission was vulnerable to cancellation, as Culberson’s loss is now demonstrating.

According to a study presented to NASA in November of 2017 but not yet completely released, the Europa lander would cost at least $2.67 billion. Considering that such cost estimates are based on early assumptions, this number would very likely grow. Thus, the lander is likely to be at least as expensive as the Mars 2020 rover and the Europa Clipper, and possibly a lot more.

In addition, the 2011 decadal survey had recommended that if NASA received additional money for planetary science, the next large strategic mission it pursued should be a mission to an ice giant planet, either Uranus or Neptune, depending upon available trajectories. An “ice giants” mission has broad scientific support, but a Europa lander does not (although once it began receiving money from Congress, many people who stood to benefit understandably started to support it.) Further, the decadal survey prioritized research, technology development, and small- and medium-class missions over flagships. The possibility of launching three flagships in a decade, particularly at a time when the small-class Discovery program and the medium-class New Frontiers program are not meeting the recommended cadence of launches, is counter to the consensus of the planetary science community.

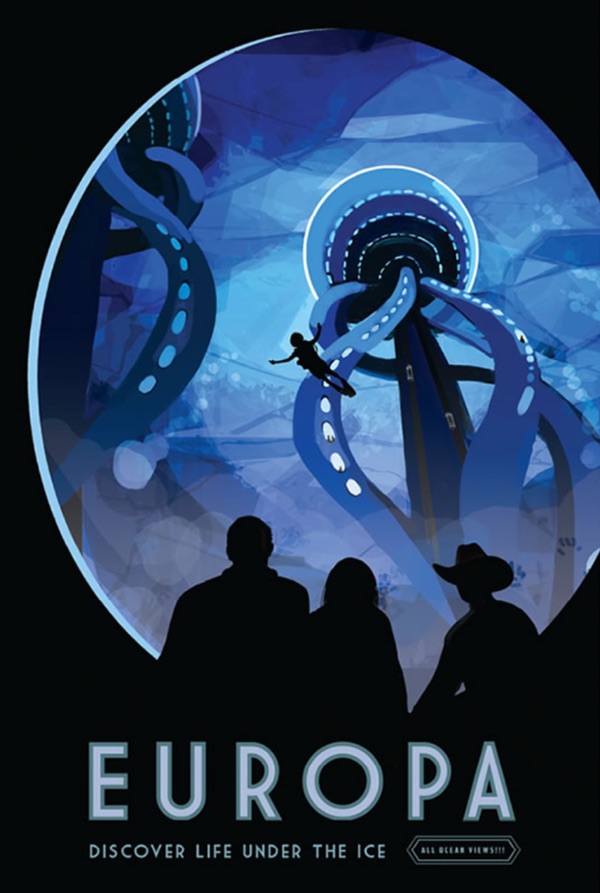

Rep. John Culberson had this picture hanging in his congressional office. He said the artist told him that the figure in the cowboy hat was supposed to be the congressman, in honor of his support for the Europa missions. (credit: NASA) |

Implications

So is the Europa lander now doomed? For the near-term, probably yes. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

| This entire episode serves as a lesson on the value of building coalitions. Reliance on a single important stakeholder can reduce the burden and time required to acquire necessary resources, but it also adds tremendous risk that said resources could disappear for reasons completely unrelated to a program or project. |

First, from a workforce and budget standpoint, NASA is already trying to finish Mars 2020 while ramping up spending on Europa Clipper. Flagship-class missions are often like “the goat that the snake ate,” in that their budget profile pushes everything else to the side as the project works its way through development, delaying other initiatives. There are rumors that JPL is already straining to provide sufficient technical staff for both Mars 2020 and Europa Clipper. Developing two flagships concurrently, or “eating two goats,” places tremendous pressure on the budget. These are very likely contributing reasons for NASA’s continued pushback on Culberson’s demand for a 2022 launch date for Clipper, though there may have been technical reasons as well. Trying to launch three flagships in four years, as Culberson’s legislation mandated, would be a feat NASA has never attempted before and the budget implications are a little terrifying. If any of the projects encountered significant cost growth, the results could be catastrophic to the planetary science community for at least a decade.

Second, the schedule NASA was being forced to follow for the lander would have pushed it into construction before Europa Clipper had even reached Jupiter. That would have locked in engineering decisions and even science observations that might not be ideal based upon what the Clipper actually finds at Europa. What would happen if the Clipper found something scientifically interesting that the lander was not designed to study? What if the Clipper discovered that the best landing site on Europa was not a place that the already-designed lander could reach?

There is a logical progression towards planetary missions: flyby, orbit, land, rove. But there is also good reason to have reasonable gaps between each mission so that the science can be assessed and the next mission can be designed to take advantage of what is learned. Assuming that Europa Clipper reaches Europa in the second half of the 2020s, it would make sense to not define a lander design before the end of the 2020s, or ten years from now. That seems like a long time, but if the goal is to do the mission properly, learn the most from the data collected, and provide taxpayers with the best return on their investment, then haste can be a bad way to do things. President Eisenhower was reportedly fond of saying, “Let’s not rush to make our mistakes.”

Third, this entire episode serves as a lesson on the value of building coalitions. Reliance on a single important stakeholder can reduce the burden and time required to acquire necessary resources, but it also adds tremendous risk that said resources could disappear for reasons completely unrelated to a program or project. Coalitions are time-consuming, unwieldy, and often unsatisfying, but they tend to be far more resilient to unexpected change. This is one of the values of the decadal survey process to the scientific community.

NASA has often relied on a small band of powerful stakeholders to ensure its political viability—and thus its funding stream—from the vagaries of governance and competition of other interests, but times are changing. Barbara Mikulski has retired, Bill Nelson is fighting to retain his Senate seat, and several prominent NASA supporters in the House lost their re-election bids this month. Other supporters in Congress will not be here forever, so NASA and the science community should be looking to cultivate relationships with a wide coalition of new and old supporters.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.