Defanging the Wolf Amendmentby Jeff Foust

|

| “A lot of people think the Wolf Amendment is a prohibition on working with the Chinese. It’s not,” said Gold. |

“While it’s probably a bridge too far to completely get rid of the Wolf Amendment,” said Brian Weeden, director of program planning at the Secure World Foundation, “it’s probably time to think about how to relax it, or at least prescribe areas where we might want to think about having cooperation with China in space.”

Weeden was speaking on a panel convened by the Secure World Foundation in March examining the state of US-China space relations. That discussion inevitably led to a review of the Wolf Amendment and its effectiveness.

Others on the panel pointed out that, contrary to many perceptions of the provision, the Wolf Amendment does allow for cooperation, under some conditions. “A lot of people think the Wolf Amendment is a prohibition on working with the Chinese. It’s not,” noted Mike Gold, appearing on the panel in his role as chair of the FAA’s Commercial Space Transportation Advisory Committee (COMSTAC).

“It says that you can work with China, but you need certification from the FBI—again totally warranted—and notification of Congress. Is that a prohibition?” he asked. “To me, those are two common sense steps right now. NASA can engage with China, has engaged with China under the auspices of the Wolf Amendment.”

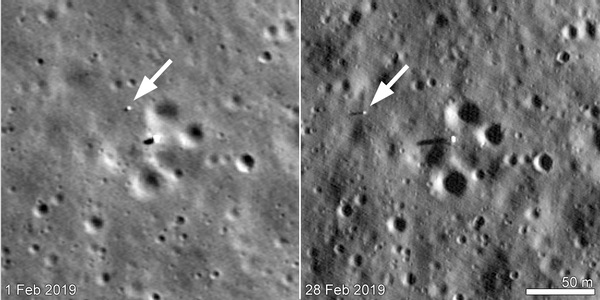

That engagement, though, has been limited to areas like aviation and Earth sciences. More recently, NASA and its Chinese counterpart, the China National Space Administration (CNSA), held discussions to coordinate observations of the landing site of China’s Chang’e-4 spacecraft by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

| “I absolutely agree that the Wolf Amendment does not prohibit cooperation, but the effect of it has been to prohibit it,” Weeden said. |

“The types of coordination that were involved, there wasn’t a formal agreement,” said Patrick Besha, senior policy advisor for strategic engagement and assessment at NASA Headquarters, on the panel. “It was more of, ‘We are going to be orbiting around the same time that you’ll be landing. Is there something we could do?’”

He added that that coordination, while “reasonably successful,” was limited to just that mission, and went through the Congressional notification and approval processes laid out in the Wolf Amendment.

Weeden argues that the amendment has a chilling effect on greater cooperation, such as in human spaceflight. “I absolutely agree that the Wolf Amendment does not prohibit cooperation, but the effect of it has been to prohibit it,” he said. Agencies are reticent to ask permission, and “the rhetoric from at least the last decade or so from many in Congress on this has been extremely critical of any US agencies that have tried to do engagement.”

There’s also the question of whether the Wolf Amendment has been effective at all in changing Chinese behavior, either in space or on Earth. That was the point raised by Todd Harrison, director of the Aerospace Security Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, during an April 25 hearing on China’s space activities by the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

“Our policy of excluding China from human spaceflight and exploration missions to the Moon and beyond has not slowed its rise as a space power,” he said. “Worse, it may create an incentive for China to build an alternative coalition for space exploration that could undermine our traditional leadership role in this arena.”

He specifically brought up the Wolf Amendment later in the hearing. “The Wolf Amendment, I believe, has largely proven ineffective in what it is was trying to do. It’s not slowing China down,” he said. “I think that we ought to look at not only repealing that, but looking at areas where we can engage China in civil space missions.”

Repealing the amendment, though, wouldn’t mean eliminating all conditions on US-China space cooperation, he continued, arguing that any cooperation should avoid the exchange of technology and “not alienate any of our existing partners in space,” such as those on the ISS. (Many of those partners, like Europe, are already engaging with China to a greater degree than the US is today.)

“I think in many places, in terms of space exploration, we do have compatible missions where we want to go to the Moon. We want to explore different parts of the moon,” he said. “There’s no reason we could not do that in conjunction with them and prevent some of the worst-case scenarios that have been talked about here of China potentially getting there first and claiming territory or rights or excluding others.”

But the debate about the Wolf Amendment raises a more fundamental question: does the US want to cooperate with China in space exploration, and vice versa?

At last October’s International Astronautical Congress (IAC), the two countries appeared willing to at least examine it. NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine met with his Chinese counterpart, CNSA administrator Zhang Kejian, and the two appeared on a panel session along with the heads of several other space agencies. “I had a very good discussion with NASA Administrator Mr. Bridenstine for bilateral cooperation in this particular area,” Zhang said of lunar exploration in particular.

“We do cooperate in a lot of ways, but that doesn’t mean our interests are always aligned,” Bridenstine said. “Some of these decisions are going to be made above the pay grade of the NASA administrator.”

“I believe that the working teams of both sides can start preparation of a cooperation list,” Zhang responded. “We can dash out those that cannot be implemented now, or are above our pay grade, and then we can start cooperating on the substantial part.”

| “My central recommendation for this commission, and for Congress, is that we need to rethink our approach to China when it comes to space. We need a multifaceted approach that simultaneously engages and deters,” Harrison said. |

At a later press conference at the IAC, Bridenstine suggested potential cooperation with China in areas like lunar exploration and space traffic management. This could be the first confidence-building measure that is necessary to establish the kind of relationship that is necessary to go to the next step,” he said.

By earlier this year, though, Bridenstine didn’t seem nearly as eager to pursue cooperation with China. “I’m not going to close that door,” he said of potential bilateral or multilateral cooperation in space exploration involving China during a February media roundtable, “but certainly it’s not a door I’m opening wide.”

NASA’s current plans for lunar exploration appear to offer few, if any, opportunities for working with China. The new sprint to the Moon, landing humans at the south pole by 2024, will largely be a US-only effort, with little role for any international cooperation beyond existing agreements, like the European-built service module for Orion. International contributions, such as modules for the lunar Gateway, will mostly be deferred to post-2024 efforts to make that presence on the Moon more sustainable.

China has its own modest international partnerships for its robotic lunar exploration program, flying instruments from several countries on the Chang’e-4 mission. It’s also expressed an openness to flying payloads, and even astronauts, from other countries on the space station it plans to construct in low Earth orbit over the next several years, although how that might extend to Chinese human missions to the Moon—whenever those take place—isn’t clear.

For now, though, there seems to be little impetus from NASA or the administration to modify or remove the Wolf Amendment, and little interest from the House, now in Democratic hands for the first time since the amendment was first placed into an appropriations bill, to change it. That may explain why it was retained in the latest CJS appropriations bill, with members choosing to focus their attention on other, higher priority issues.

But experts like Harrison think the overall approach the US takes to working with, or competing against, China in space needs to be reconsidered. That April commission meeting focused more broadly on Chinese space activities, including the development of anti-satellite weapons and other capabilities that could threaten American space assets, particularly during a conflict involving the two nations.

“My central recommendation for this commission, and for Congress, is that we need to rethink our approach to China when it comes to space. We need a multifaceted approach that simultaneously engages and deters,” Harrison said. “We should engage China proactively in civil space programs when we have shared goals and when our intellectual property and existing space partnerships are adequately protected.” But, he added, “as we engage China more openly in civil space, we should simultaneously make a concerted effort to improve our deterrence posture in national security space.”

“China is a rising space power,” he concluded. “Our policies must recognize this fact and adapt accordingly to protect our economic and security interests in space.”

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.