How many spaceports are too many?by Jeff Foust

|

| “I’m a little concerned that there’ll be such a rush to do that that we’ll have too many spaceports,” Ross said last year. |

But there are many more launch sites in the country than those. The FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation has 11 active “launch site operator,” or spaceport, licenses for facilities across the US. Of those 11, five are for facilities that have yet to have a launch or landing: Midland International Air and Space Port in Texas, Colorado Air and Space Port near Denver, Oklahoma Air and Space Port, Ellington Airport (aka Houston Spaceport), and Cecil Field in Jacksonville, Florida. (A sixth belongs to Space Florida for the Shuttle Landing Facility runway, which the state agency now operates commercially; it has yet to be the site of any commercial launches but, of course, hosted dozens of Space Shuttle landings.)

Some of those licenses are legacies of ventures that have gone away: Oklahoma was to be the home of Rocketplane Global’s suborbital vehicle, and Midland the home of XCOR Aerospace, two companies than have since gone bankrupt. Others are still waiting for their customers to be ready, like Cecil Field, which has been working with air-launch companies Generation Orbit and Aevum.

Still, there’s the perception that there are too many spaceports out there, particularly when many of the ones that do host launches are nowhere near capacity. That’s a view shared by, among others, Wilbur Ross, the Secretary of Commerce, who has otherwise been an advocate for the commercial space industry.

“I’m a little concerned that there’ll be such a rush to do that that we’ll have too many spaceports,” Ross said of developing launch sites in a media teleconference last year. “What you’ll end up with is a lot of ghost facilities.”

A former FAA official doesn’t see that way. “I strongly disagree with that assessment,” said George Nield during a presentation in October at the International Symposium for Personal and Commercial Spaceflight (ISPCS) in Las Cruces, New Mexico.

Nield, who retired from the FAA in early 2018 as associate administrator for commercial space transportation, made the case that, in fact, more spaceport infrastructure is needed. “Our current spaceport infrastructure is very limited and is rather fragile and vulnerable,” citing threats to facilities in California from natural disasters ranging from earthquakes to hurricanes.

In his speech, he argued that the US government should invest more in spaceports, including developing a national spaceport policy. That would help provide infrastructure funding for spaceports, similar to grant programs for airport improvements, and also highlight their role in economic and workforce development.

“Instead of just viewing spaceports as locations from which launches and reentries are conducted, I think it’s also important to recognize that they can serve as focal points and technology hubs,” he said.

Nield made a similar case last month at a meeting in Houston of the Global Spaceport Alliance, a group of spaceports primarily in the US but including proposed sites in the UK, Japan, and Latin America. He said he’s talked with Scott Pace, executive secretary of the National Space Council, and Jim Ellis, chair of the council’s Users’ Advisory Group, on the issue. “They’re in the process of lining up some folks,” Nield said, “to see what kinds of things the Space Council should be talking about when it comes to spaceports.”

| “Instead of just viewing spaceports as locations from which launches and reentries are conducted, I think it’s also important to recognize that they can serve as focal points and technology hubs,” Nield said. |

Nield, who chairs the Alliance, spoke to a receptive audience. Attendees ranged from relatively well-established spaceports like Spaceport America to sites still in the early planning stages and not deterred by the lack of activity at existing spaceports. The latter included Yuma, Arizona, which is proposing a site for hosting small orbital launch vehicles launching south over the Sea of Cortez (a trajectory they acknowledged will require coordination with the Mexican government) to Hancock County, Mississippi, which is starting the FAA license application process for Stennis International Airport, a general aviation airport not far from NASA’s Stennis Space Center.

They, and others, didn’t see the lack of launch companies as a deterrent to their plans. At the meeting, officials with Houston Spaceport emphasized the success they had attracting businesses even without hosting launches.

“We determined that there were too few players, in terms of operators,” said Arturo Machuca, general manager of Ellington Airport and Houston Spaceport. “We decided we were not going to build our business case immediately around operations.”

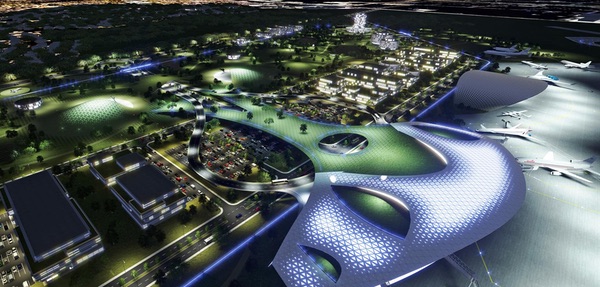

Instead, they’ve put their emphasis on building up the site as a launch pad for businesses, rather than rockets. Houston Spaceport has been working on “phase 1” of a business park, putting in roads and other infrastructure to support companies seeking to set up operations there. That includes Flight Safety International, which announced plans earlier in the fall to set up an aviation safety training center there, as well as commercial lunar lander developer Intuitive Machines.

Machuca claimed that wouldn’t be possible without being licensed as a spaceport. “The economic impact that we’re seeing is now tangible. It’s making a difference,” he said. “It would not have been possible without Houston Spaceport being recognized and licensed as an operational spaceport.”

Other spaceports are following Houston’s lead. Colorado Air and Space Port has had success attracting companies that want to do engine testing at the former Front Range Airport. That includes Reaction Engines, the British company that is testing its SABRE engine at the site.

All that continues while the spaceport continues as a general aviation airport. “When you do something with space, it doesn’t preclude the other activities. The two things are very easily integrated,” said David Ruppel, director of the spaceport.

Plans for Colorado Air and Space Port to host launches attracted opposition from some in the aviation business, in part because the airport is only about ten kilometers from Denver International Airport. The FAA went ahead and gave the airport a spaceport license, since any airspace conflicts would have to be addressed later on a vehicle-by-vehicle basis—and there are no near-term prospects for launches from there.

Spaceport Cornwall, at Cornwall Airport Newquay, will host air-launch operations for Virgin Orbit. (credit: Spaceport Cornwall |

Other potential spaceports have run into other kinds of opposition. Earlier this year, Alaska Aerospace Corporation, which operates Pacific Spaceport Complex – Alaska on Kodiak Island, announced plans to establish a launch site on private property on the Big Island of Hawaii. The facility would host small launch vehicles for launches to low-inclination orbits, complementing the Alaska site’s support for launches to polar orbits.

The proposal, though, faced strong public opposition from residents in nearby communities, who opposed the site on environmental grounds. “There was a lot of backlash,” said Mark Lester, president of Alaska Aerospace, at the Global Spaceport Alliance meeting. In October, that private landowner, W.H. Shipman Ltd., announced it was dropping out of the project.

Hawaii is not an isolated case. In Georgia, local residents are opposed to plans to establish a spaceport in Camden County, near the Atlantic coast, in part because of environmental concerns. A final environmental impact assessment is expected to be released in the coming weeks, after which the FAA will decide whether to award the proposed site a spaceport license.

| “The level of scrutiny we have will increase,” Carden said, suggesting that spaceports band together to share data on environmental issues. “If we don’t do that, our industry will be destroyed. It’s an easy target.” |

In Britain, protestors gathered last month at a meeting of a local government body, the Cornwall Council, which was considering whether to appropriate about £10 million (US$13.1 million) for infrastructure improvements at Cornwall Airport Newquay to support air-launch operations by Virgin Orbit. Protestors claimed allowing launch activities there contradicted local efforts to reduce carbon emissions.

Prior to the vote, spaceport officials commissioned a study to study that specific issue. “There was very little data out there about the total carbon impact of launch,” said Miles Carden, director of Spaceport Cornwall, at the Alliance meeting. That report found that allowing launches from the airport would not have a significant impact on the region’s carbon footprint—not surprising, since Virgin Orbit is likely to conduct, at best, a few launches a year using its Boeing 747 taking off from an airport that already hosts many more commercial airline flights a day.

Despite the protestors, the Cornwall Council approved the spaceport funding by a two-to-one margin, covering about half the cost of the work there (the British government and Virgin Orbit are covering the rest.) Carden, though, thinks similar environmental arguments could be used against other spaceports in the future. “The level of scrutiny we have will increase,” he said, suggesting that spaceports band together to share data on the issue. “If we don’t do that, our industry will be destroyed. It’s an easy target.”

Lester, with plans for a Hawaii launch site now “paused,” is focusing on building up launch activity at Kodiak, and dealing with locals there who oppose the spaceport. “We still have our ‘fan club’ that doesn’t want us to be there,” he said. “But I think we’ve done some things to improve the relationship.”

That includes better coordination of airspace and waterway closures for launches to minimize impacts on the island’s dominant fishing industry. “That’s a legitimate concern,” he said. “We have to integrate into their way of life.”

Despite the environmental and public opinion challenges, and the lack of demand, new spaceports keep coming, as last month’s Global Spaceport Alliance meeting demonstrated. Even those that have found success with things like business parks aren’t giving up on hosting spaceflight. “We do believe, without hesitation, that point-to-point transportation will become a regular way of traveling,” Houston’s Machuca said, while acknowledging he didn't know when point-to-point suborbital spaceflight might actually emerge as a viable market.

Nield, at ISPCS, noted that there are thousands of airports in the US alone, from major commercial airports to tiny general aviation facilities, yet rarely do you hear complaints that there are too many airports.

“How many spaceports do we need?” he asked. “As many as it takes to ensure our national security, to maintain technological leadership, enable international competitiveness and provide inspiration for students and development of our aerospace workforce.”

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.