Panchromatic astronomy on a budgetby Jeff Foust

|

| “Hubble is in good technical condition and is right now, even after 30 years, at the peak of its scientific return,” said Wiseman. |

To confirm TOI 700 d was a real planet, astronomers turned to another, venerable spacecraft: the Spitzer Space Telescope. “We wanted to be absolutely sure that this was real as well as really refine our understanding of the planet,” said Joseph Rodriguez, an astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics (CfA) | Harvard & Smithsonian, during the briefing. Those observations by Spitzer confirmed the planet was real and helped constrain its orbit and size, he said, adding that Spitzer performed another observation of the planet as it transited in front of its star just the day before the briefing.

But Spitzer’s days are coming to an end. On January 30, NASA will transmit the final commands to the space telescope, instructing it to shut down. Launched in 2003 into a heliocentric orbit, NASA announced last year it would shut down the spacecraft because of its age, and complications with communications and spacecraft operations as the spacecraft’s distance from the Earth increases. (NASA briefly considered handing over Spitzer operations to a private organization who would cover the costs of doing so, but none with both the interest and the budget stepped up.)

Spitzer, originally known as the Space Infrared Telescope Facility, was the last of NASA’s original four “Great Observatories” to launch. The Compton Gamma Ray Observatory, launched in 1991, deorbited in 2000 after suffering failures of several of its gyroscopes. That leaves the Chandra X-Ray Observatory and the Hubble Space Telescope as the two surviving Great Observatories after this month.

Both Chandra and Hubble are getting old, though: astronomers marked the 20th anniversary of Chandra’s launch last year, while the 30th anniversary of Hubble’s launch is this April. Both are operating well, but have suffered technical glitches in recent years that, at the very least, are a reminder that neither will be around forever.

“The observatory is in great shape, even today,” said Jennifer Wiseman of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center about Hubble during a seminar about the telescope’s upcoming 30th anniversary at the AAS meeting. “Hubble is in good technical condition and is right now, even after 30 years, at the peak of its scientific return.”

Wiseman and other astronomers expect—or at least hope—that Hubble will continue to operate well into the 2020s. Three of Hubble’s six gyros have failed, but Wiseman said the three that failed are all of the same design while the other three are of a different design that appears to be longer lived. The spacecraft, she added, could operate on just a single gyro.

“We don’t know how long Hubble is going to last, but as long as Hubble is being scientifically productive, NASA is, at least now, committed to supporting it,” she said.

| “I don’t think that NASA should do just one of these missions. I think we should do all of these of these missions. These are our next Great Observatories,” said Hertz. |

There are, of course, new space telescopes in development. The long-delayed James Webb Space Telescope is set to launch in March 2021, while the Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST) will follow in 2025. Both those spacecraft, though, are optimized for observation in the infrared. Hubble, Wiseman argued, is “critically complementary” to those new space telescopes given its ability to observe at visible and ultraviolet wavelengths.

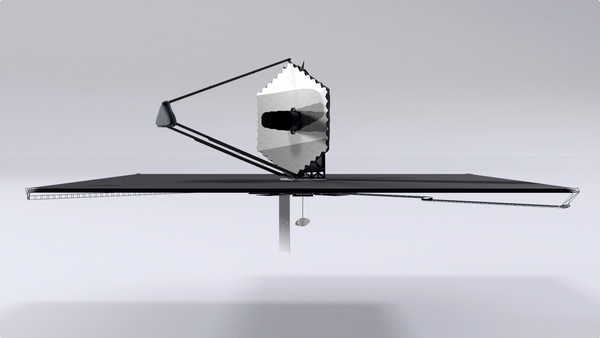

An illustration of the larger variant of LUVOIR, one of the large space telescope missions under consideration in the 2020 astrophysics decadal survey. (credit: NASA) |

New Greats and Giant Leaps

Another flagship space observatory could start development later this decade. NASA commissioned studies for four concepts, spanning the electromagnetic spectrum—HabEx, LUVOIR, Lynx, and Origins Space Telescope—that were completed last year and provided to the National Academies committee working on the latest astrophysics decadal survey, called Astro2020 (see “Selecting the next great space observatory”, The Space Review, January 21, 2019). That committee’s final report, due in about a year, will likely select one of those mission concepts as the top-priority flagship mission for the next decade, recommending that NASA fund its development.

Those concept studies have won high praise in the community for advancing the maturity of those proposed missions to a far greater degree than concepts proposed for previous decadal surveys. Some astronomers have suggested that the four missions band together as a sort of “New Great Observatories,” seeking the eventual development of all four.

“I don’t think that NASA should do just one of these missions. I think we should do all of these of these missions. These are our next Great Observatories. These are the missions we need to continue the multi-wavelength astrophysics that we have all grown used to over the last 30 years,” Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s astrophysics division, said during a NASA town hall meeting at the AAS conference. “I’m hopeful we can continue working on all of them so that we can launch them in series.”

Doing so, though, will take time. A “wedge” in NASA’s astrophysics budget for the next flagship mission will only start to open up towards the middle of the decade, as WFIRST nears launch. Hertz estimates that there’s about $5 billion a decade available for flagship missions, or perhaps $7 billion given more optimistic projections of the agency’s budget. Most in the field don’t expect that the mission that is selected as the top priority by Astro2020 to fly before about the mid-2030s, given those budget constraints. Both Chandra and Hubble may be defunct by then.

A report last year by a NASA science analysis group examined the potential gaps in wavelength coverage caused by the eventual demise of the original Great Observatories. Was that multi-wavelength, or “panchromatic,” coverage offered by the Great Observatories still important today? And, if so, how could it be maintained?

The answer to that first question was a clear “yes.” In the report, and a session about it at the AAS conference, astronomers discussed how having infrared, visible, ultraviolet, X-ray, and gamma-ray observations can work in conjunction in fields from exoplanets to galactic evolution to fundamental properties of the universe.

“A lot of the galactic science that we want to push forward in the next decade will require multiple wavelengths,” said Massimo Marengo of Iowa State University. “Also, we require it to be there at the same time so we can combine observations.”

| “Commensurate and concurrent capabilities can be achieved with a range of mission sizes and costs,” said Armus. “If you’re smart, you can do it with a mix.” |

A gap in that panchromatic coverage can have repercussions beyond the science itself. “There’s a community cost, too,” said Martin Elvis of the CfA. Such a gap discourages students from entering the field, creating a loss of “implicit knowledge” as those currently in the field retire without passing it on to a new generation. It would also discourage people from developing more advanced instruments, he said, since there would be no opportunity to fly them.

“It leads to a greater science cost yet,” he concluded. “You’ll basically be shutting down large areas of astrophysics.”

The report’s recommendation to address the science and community problems created by a gap wasn’t to simply build new flagship space telescopes. “At current funding levels, NASA clearly cannot develop three ~$9B strategic missions simultaneously in the next decade, or even two,” the report acknowledged.

Instead, it called for a mix of both flagships and smaller missions, a combination it dubbed the “Giant Leap Observatories.” That approach offers a more affordable way of providing some degree of panchromatic coverage while fitting into realistic budget scenarios at NASA.

“Commensurate and concurrent capabilities can be achieved with a range of mission sizes and costs,” said Lee Armus of Caltech, co-chair of the study. “If you’re smart, you can do it with a mix.”

As the report noted, not all of the Great Observatories would be considered flagship-class missions today. The report estimated that Hubble cost, at the time of its launch, $9.2 billion in 2019 dollars, about the same cost as JWST. Chandra, though, cost just $3 billion in 2019 dollars, a little less than the current $3.2 billion cost cap for WFIRST. And Compton and Spitzer cost just $1.2 and $1 billion, respectively, about the same as a “probe-class” astrophysics mission.

There is interest in NASA in pursuing a probe-class mission in parallel with JWST and WFIRST. NASA commissioned ten studies of probe mission concepts that, like the ones for the flagship missions, will feed into the Astro2020 decadal survey. Hertz said that NASA’s future budget projects include a funding wedge starting in 2022 for a probe, if the decadal recommends the development of one or more such missions.

Hertz, in another session of the AAS conference, lamented the fact that the 2010 decadal survey didn’t recommend a medium-class mission. “I was personally disappointed” the decadal didn’t endorse such a mission, he said, arguing that, early in the decade, there would have been agency support for it. “If a probe had been recommended in the 2010 decadal survey, we would have been allowed to start it right away. It would have launched by now.”

Those involved in the report on the Giant Leap Observatories concept hope to see some sort of consensus emerge in the broader astrophysics community for implementing its recommendations, perhaps with the Astro2020 report. “We should all get on the same page for developing a grand plan to carry out panchromatic science that we need,” said Stephan McCandliss of Johns Hopkins University.

Until then, astronomers are planning for a future without two of the four Great Observatories. While Spitzer’s infrared capabilities will ultimately be replaced, and greatly improved upon, by JWST and WFIRST, the end of Spitzer will leave some astronomers, like CfA’s Rodriguez, without many other options in the near term.

Asked at the press conference how he and colleagues would have confirmed TOI 700 d without Spitzer, Rodriguez said they had only a few other options, like the European Space Agency’s newly launched Characterizing Exoplanets, or Cheops, spacecraft. “That just shows the power of what Spitzer was able to do,” he said. “It is a bit limited without Spitzer, and I think that’s a key thing to make clear.”

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.