Mars in limboby Jeff Foust

|

| “This is a very tough decision, but it’s I’m sure the right one,” said Wörner. |

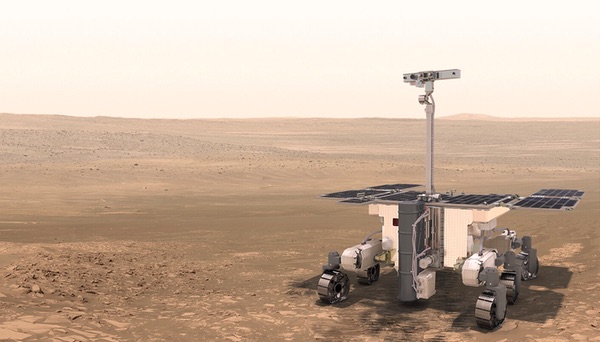

One of those four, though, won’t make it this year. The European Space Agency announced last Thursday that, in cooperation with the Russian state space corporation Roscosmos, it was delaying the launch of the ExoMars mission that had been scheduled for July on a Proton rocket. The mission will carry to the surface a lander, called Rosalind Franklin, whose missions includes the search for evidence of past or present life on the planet.

Technical issues, ESA leadership said, meant that the spacecraft could not be completed and fully tested in time to meet the narrow launch window this summer. “This is a very tough decision, but it’s I’m sure the right one,” Jan Wörner, director general of ESA, said in a media teleconference.

Among those technical problems was a long-standing concern with the spacecraft’s parachutes, which include parachutes 15 and 35 meters in diameter with accompanying drogue chutes. In one high-altitude deployment test in May in Sweden, both the 15- and 35-meter parachutes were damaged. In a second test in August, also in Sweden, the 35-meter parachute was damaged.

An investigation into the problems found that the parachutes were being torn while being extracted from their containers. ESA turned to NASA for help in redesigning that system and performing a series of ground tests at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. That was to be followed by a pair of high-altitude deployment tests, this time in Oregon.

Those tests had been scheduled to be completed by now, but have been delayed. “There are some competing priorities over there” at that US test site, Wörner said, “so this will be a little bit later than we hoped.” He later said the tests would be postponed by weeks, rather than months.

In past briefings and interviews, ESA officials were optimistic that the parachute problem had been solved and that the testing could be completed in time for a 2020 launch. “My information is that we are now on a good side. This is not any obstacle for the flight in the summer of this year,” Wörner said at a January 15 press briefing.

One reason for that was that the parachutes could be installed on the spacecraft late in the overall integration process. “As long as we have proven that the parachute works, it can be integrated very late in the assembly sequence,” David Parker, ESA’s head of human and robotic exploration, said in an interview last October during the International Astronautical Congress in Washington.

In addition to the parachutes, Wörner said there were problems with four electronics boxes on the spacecraft that required them to be replaced, although he did not elaborate on the specific problems they suffered.

Those problems, in turn, delayed the completion and testing of software for ExoMars. “There is not enough time left to fully test it before a 2020 launch and gain the confidence we need,” he said. “We could launch, but that would mean we are not doing all the tests and, from the experience we had with Beagle and Schiaparelli, and the clear messages we got, I got as director general, was a very harsh, clear message: do all the tests before you launch.”

| “We’ve been keeping pushing up to, let’s say, one month ago,” said Francois Spoto, ExoMars team leader. |

Beagle is a reference to Beagle 2, a British-built Mars lander flown with ESA’s Mars Express mission in 2003 that failed to make contact after landing. Imagery taken of the landing site suggests the spacecraft did land, but could not deploy its solar panels and thus never made contact. Schiaparelli was an experimental spacecraft flown with the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter mission in 2016, which crashed when a software problem caused the lander’s computer to shut off its thrusters while still several kilometers above the surface.

“We cannot really cut corners,” Wörner said. “Launching this year would mean sacrificing essential remaining tests.”

“The learning curve should be at the maximum” by the time ExoMars arrives at Mars, he said later. “We would like to be as sure as possible, as certain as possible, when we go to Mars that we at least have done all the tests to show that it is possible to land on Mars. It really is a hard thing.”

The announcement confirmed growing speculation that the mission would be delayed, and ESA officials acknowledged that, despite the optimistic talk as recently as January, they shortly thereafter realized that the 2020 launch could not take place. “We’ve been keeping pushing up to, let’s say, one month ago,” said Francois Spoto, ExoMars team leader.

Once the parachute tests, electronics work, and software testing are all completed, the spacecraft will go into storage until the next launch window, between August and October of 2022. ESA hasn’t determined the cost of the delay, Parker said in last week’s teleconference, but noted there is a “risk mitigation budget” for the mission as part of the broader Mars exploration program funded at last year’s ministerial meeting (see “Funding Europe’s space ambitions”, The Space Review, December 2, 2019).

There was another complicating factor in the decision to delay ExoMars: the spread of the coronavirus disease COVID-19, which the World Health Organization declared a pandemic last Wednesday. In ESA’s press release about the launch delay, Dmitry Rogozin, head of Roscosmos, cited “force majeure circumstances related to exacerbation of the epidemiological situation in Europe which left our experts practically no possibility to proceed with travels to partner industries.”

Wörner said in the media teleconference that the pandemic had affected launch preparations, but wasn’t the main reason for the delay. “To say the coronavirus is the one and only reason would not at all be fair, but in this situation we see that the coronavirus has also an impact on the preparations” because of travel restrictions, he said. “I would not like to say the coronavirus is the one and only reason.” (It did have an effect on the briefing, which was originally scheduled to be a joint ESA-Roscosmos press conference in Moscow. Instead, it was held as a video teleconference at ESA headquarters in Paris, with reporters emailing their questions.)

He declined to speculate whether, had everything else with ExoMars been going well, the launch would have been delayed anyway because of the pandemic. “I don’t know,” he said. “It’s ridiculous to look back at history. Let’s look forward.”

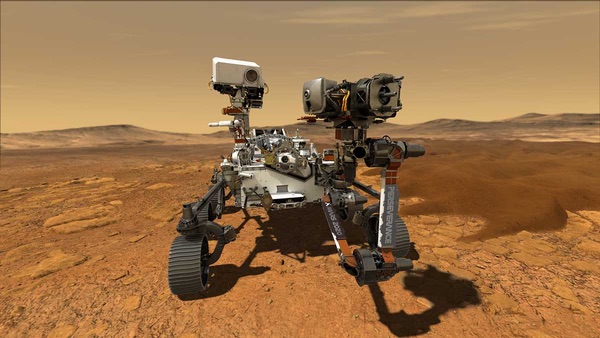

It’s not a hypothetical concern, though, for the other three missions being prepared for launch to Mars this summer. NASA’s Mars 2020 mission, with a rover recently named Perseverance, is undergoing preparations at the Kennedy Space Center for a launch on an Atlas 5 in July.

An illustration of Perseverance, the Mars 2020 rover, still on schedule for launch in July. (credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech) |

“We are green across the board,” Jim Watzin, director of NASA’s Mars Exploration Program, said of Mars 2020 at a March 9 meeting of NASA’s Planetary Science Advisory Committee. “The team is working hard and they’re on schedule, and we’re still carrying significant schedule reserve to our launch date on July 17.”

| “If we can no longer travel across the United States, if basically people need to be isolated, how do we prioritize the mission work that needs to be done? What are the things that are absolutely urgent that need to go forward?” said Zurbuchen. |

However, uncertainty about the length and severity of the pandemic, and its effect on various industries, weighs on all of NASA’s programs. Two of the agency’s centers, Ames in California and Marshall in Alabama, have moved to “mandatory telework” after employees were diagnosed with COVID-19, although “mission-essential” personnel can still work on site. NASA is encouraging telework at other centers, and it may be only a matter of time—days, perhaps—before other centers adopt similar mandatory telework requirements to combat the spread of the disease.

“At this moment in time, I would say that is the biggest risk, how the impact of that affects some of these missions,” Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA associate administrator for science, said of the pandemic during a virtual meeting last Thursday of the NASA Advisory Council’s science committee. He said teams at JPL and KSC were planning various scenarios “to make sure that we can, in fact, keep this on track.”

“We have a lot of ambiguity at this moment” about the effects of the pandemic, he said later in the meeting. “If we can no longer travel across the United States, if basically people need to be isolated, how do we prioritize the mission work that needs to be done? What are the things that are absolutely urgent that need to go forward?”

He said missions like Mars 2020 that have narrow launch windows would likely be prioritized. That would also include Lucy, an asteroid mission with a complex trajectory that requires a launch in October 2021, and Psyche, another asteroid mission in 2022. That would be followed missions in advanced stages of integration and testing, including the James Webb Space Telescope and Landsat-9.

There’s less information about the status of two other Mars missions. China’s space program, like the rest of the country, has been slowed by the coronavirus outbreak that started there. The Xinhua news service reported last week that the Beijing Aerospace Control Center completed a test to confirm that mission control could communicate with and operate its Mars mission, which includes an orbiter, lander, and rover.

“According to the center, the test has not been affected by the novel coronavirus epidemic, and the technical staff is working hard to ensure the success of the mission,” Xinhua reported. That mission is scheduled for launch on a Long March 5 rocket—which returned to flight last December nearly two and a half years after a launch failure—this summer. (That could be in jeopardy after the failure, as this article was being prepared for publication, of a Long March 7A rocket, which shares some components with the Long March 5.)

The United Arab Emirates Space Agency has provided few recent updates on its Hope Mars mission. That spacecraft is an orbiter built in the UAE and recently tested in Colorado. It is scheduled for launch in July on an H-2 rocket in Japan, a date the agency confirmed in a March 16 tweet.

Travel restrictions in response to the pandemic could make it difficult for the spacecraft and personnel to get to Japan for the launch this summer. However, the UAE would like to see the mission launch this summer so it can arrive in early 2021, the 50th anniversary of the UAE’s founding. And, right now, the world could use a little hope.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.