Letter to the editor: space weapons debateby Theresa Hitchens

|

| There are no anti-satellite weapons currently aimed at US satellites nor are any such weapons deemed likely, even by proponents of space weapons, in the next decade. That is to say that while satellites may be inherently vulnerable, at the moment they are not threatened. |

My work was subsidized from CDI’s general fund (rather than the subject of a specific grant or fundraising effort) until May 2003, when I received a dedicated grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York, which came due to the Corporation’s interest in my earlier work. (My current Carnegie grant of $300,000 covers October 2004 through September 2006). Total direct contribution to my efforts by the general public thus far has been one donation of $100, given in an unsolicited check rather than through any space-related funding drive on the part of CDI. Finally, I have been assured that CDI will continue to support my work through its general operating budget of about $4 million (2004)—a sum that is roughly one-tenth of that of the Heritage Foundation, a leading advocate of space weapons—no matter whether specific future funding can be acquired or not. The point I am trying to make here is that while CDI, like any other non-profit, must raise money in order to survive, the organization does not choose the topics of its research—nor, in fact, do I choose the topics of my own work—based on a calculation of what will raise the most money, as implied by Mr. Dinerman. Rather, our mission statement (available on www.cdi.org) is clear about the topics we cover and why—that is, to ensure an informed public debate about critical security issues.

I will limit my further critique of Mr. Dinerman’s article to only a few points:

- There are no anti-satellite weapons currently aimed at US satellites nor are any such weapons deemed likely, even by proponents of space weapons, in the next decade. That is to say that while satellites may be inherently vulnerable, at the moment they are not threatened. Primary requirements to reduce those vulnerabilities are protective measures—through physical safeguards especially to ground-stations, technology improvements such as jam proofing, and increased system and subsystem redundancy—rather than offensive systems. The biggest current threat to space assets is actually space debris; and the most urgent requirement for satellite protection is improved space surveillance—something the US Air Force is rightly putting a near-term priority on and an effort that ought to be further encouraged.

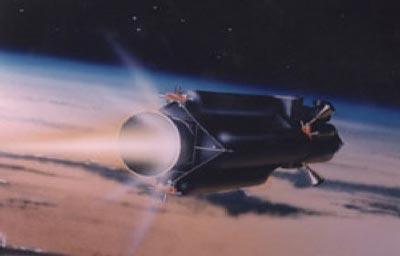

- The current interest in anti-satellite and space strike weapons by the US Air Force is based on an offensive strategy, rather than a defensive one. That strategy is aimed at denial of space services, such as communications and mapping information, to an adversary on a future battlefield, as well as speeding attack against distant targets. When looked at from a strictly tactical, battlefield view, one can see the logic of commanders wishing to have such capabilities. However, it is at least a question to be raised as to whether pursuit of a near-term tactical advantage in space will result in a mid- and long-term strategic disadvantage.

- US Air Force long-range plans for a varied arsenal of offensive space capabilities are official and publicly documented. While current identifiable spending in what Dick Garwin has called a “technological sandbox” for space weaponry is relatively small, overall space spending is set to continue its steep upward trajectory at least through 2010. About half the total DoD space budget (the FY 2006 request was $21.5 billion, up from $14.3 billion in 2001) is classified. Therefore, unless Mr. Dinerman has a security clearance and access to the classified space budget, his assessment of what is or is not being spent, or what is planned in the budget out-years to be spent, on enabling technologies for space warfare can be no better than mine or any other outside analyst.

In the interest of civil, open and honest debate—which is the foundation of our democracy—I can only hope that your publication, and others, will refrain from the ugly politics of the personal represented by Mr. Dinerman’s article and concentrate on the extremely important substantive issues surrounding future US space policy.