Outer space needs private lawby Alexander William Salter

|

| Undoubtedly, space must be governed. But governance is not the same thing as government. |

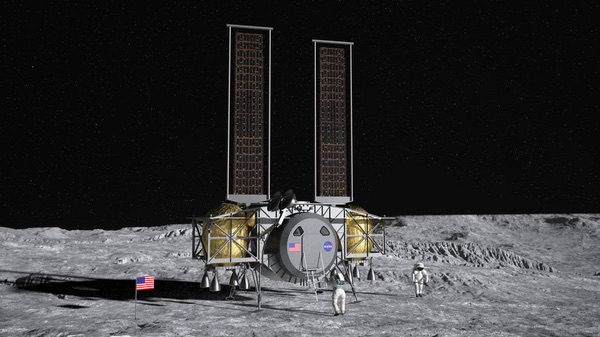

To see why, we need to understand recent developments in space policy that have raised the stakes of celestial statecraft. NASA recently announced the Artemis Accords, a series of bilateral agreements to establish standards and procedures for future space missions. The Accords are intended to secure buy-in from US allies that are also spacefaring nations, with the goal of cooperating on NASA’s ambitious Artemis program to return humans to the Moon. Russia seemed like a natural partner, due to the successful collaboration with the US on the International Space Station.

Instead, there was a falling out. Russia and China view the Artemis Project and Accords as a space version of NATO: a politically motivated attempt to extend US hegemony. “Frankly speaking, we are not interested in participating in such a project,” said Dmitry Rogozin, the head of Russia’s space agency. Russia sees the US initiative as an attempt to privatize space, which in practice means celestial domination by whoever gets there first. China evidently agrees. Indeed, Rogozin spoke warmly about collaboration with the Chinese, affirming that they’re “definitely our partner.”

This is bad news, but we could avoid the dangers of factionalism if we use private law to eschew jurisdictional claim-staking in space. Preserving a neutral domain in which the spacefaring nations can interact to mutual advantage would help keep the peace. That much has been understood for over half a century. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, still the backbone of public international space law, explicitly forbids the extension of government jurisdiction to the heavenly bodies.

Thus alleged privatization by the US, such as a 2015 law guaranteeing US nationals property rights to celestial resources, as well as a recent executive order encouraging the commercial development of space, is perceived as contrary to the spirit of the treaty. America’s space rivals are on high alert to the extension of US sovereignty into space by extralegal means.

Strictly speaking, these US initiatives are consistent with international treaty obligations. Combined with Artemis, they represent significant steps forward in humanity’s journey into space. Nevertheless, Russia and China fear there’s a political motive lurking behind these economic policies. In the interests of peace and cooperation, the US should extend an olive branch not by retreating on Artemis, but by promoting private law.

Spacefaring nations can thrive under this system of governance, but only if states don’t compete for sovereignty. For example, just look at international commerce.

Trade between nations often involves entities from different jurisdictions. If they have a commercial dispute, no national court can hear the case. But this doesn’t mean international commerce is lawless—far from it. These disputes are privately adjudicated and voluntarily enforced by the traders themselves. A private body of self-enforcing law, dating back to the High Middle Ages, evolved to meet the needs of merchants. There are even organizations, such as the International Chamber of Commerce and the International Center for Dispute Resolution, that specialize in arbitrating these conflicts.

| The development of a private body of space commercial law is the best way to keep the peace in space. Unlike privatization, private law doesn’t raise geopolitical red flags. |

Much of international commercial law can apply to space. In addition, the Permanent Court of Arbitration already offers guidelines for arbitrating space disputes. But this doesn’t mean only private entities will govern space. States still have an important role to play. For example, spacefaring nations should uphold treaty obligations by policing their nationals, making sure nobody tries to homestead a planet in a fit of hubris. This still leaves plenty of room for non-jurisdictional (and, hence, private) space activity.

The development of a private body of space commercial law is the best way to keep the peace in space. Unlike privatization, private law doesn’t raise geopolitical red flags. In these early years of Space Age 2.0, we must all work to prevent international conflict from stifling space exploration and development. Only then will humanity be free to extend its reach to the stars.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.