The three administratorsby Jeff Foust

|

| “I just have full confidence in the NASA team that they’re going to do the right thing. I don’t think they need any help from me in terms of telling them where they ought to go,” said Goldin. |

Goldin participated in an Aviation Week webinar last Friday along with two other former administrators: Sean O’Keefe, who served from the beginning of 2002 through 2004, and Charlie Bolden, who led the agency from the middle of 2009 to the beginning of 2017. The three didn’t provide any direct, specific advice for current NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine, but instead spent an hour talking with Aviation Week’s Irene Klotz on some of the issues and challenges they faced, which remain relevant today.

China cooperation and competition

A long-running debate has been whether, and how, NASA should cooperate with China in space exploration. Goldin recalled a 1996 trip to China with the presidential science advisor and director of the National Science Foundation. “We spent the whole day with Jiang Zemin, the president of China, talking about space,” he recalled. That included a request by Jiang for China to join the International Space Station.

“In a very respectful way, I said, ‘The day you join the Missile Technology Control Regime is the day we’ll begin talking to you about joining the International Space Station,’” Goldin said, comparing it to “open, honest discussions” with Russia about proposed sales of missile technology. (China today has yet to join the MTCR.)

In 2010, Bolden went to China to discuss potential collaboration. That trip, he recalled, included astronaut Peggy Whitson and Bill Gerstenmaier, head of NASA’s human spaceflight programs, to meet with Chinese officials and evaluate their technology. “They were able to climb all over everything,” he said. “Peggy said, ‘No, it’s not Russian, but it’s awfully close.’”

Any potential cooperation, he said, had to incorporate transparency, reciprocity, and mutual benefit. “We had everything all drafted out to sort of mirror Dan’s approach to the Russians,” he said. “We went back into the archives and got all of the paperwork out. We scratched out ‘Roscosmos’ and put in ‘CNSA’ [China National Space Administration] and scratched out ‘Russia’ and put in ‘China.’”

“We were pretty close, but we could not get it past Congressman Frank Wolf,” he said. Wolf, who chaired a House appropriations subcommittee that funded NASA, was a strong opponent of cooperating with China because of human rights concerns. He inserted language in an appropriations bill severely restricting any cooperation between NASA and Chinese organizations, and that “Wolf Amendment” lives on in appropriations bills to this day.

Some want to revisit, and potentially strengthen, that language. A provision in a NASA authorization bill currently pending in the Senate reiterates the restrictions of the Wolf Amendment but also directs a review by the GAO of NASA’s contracts to identify any contractors that are controlled by or otherwise benefit from assistance from the Chinese government. It also directs NASA to, in its contracting process, “take into account the implications of any benefit received” by a company or organization from the Chinese government or any entity controlled by or affiliated with the Chinese government.

The backer of that provision, Sen. Cory Gardner (R-CO), is motivated not by human rights concerns about technology transfer. “We know that Chinese actors are stealing intellectual property from American businesses,” he said at a Senate Commerce Committee hearing September 30 about NASA programs.

| “I think the entire objectives that were laid out by President Bush and his Vision for Space Exploration is exactly what we’ve seen come to pass in the last 15 years,” O’Keefe said. |

To some, Gardner’s language is too broad, since it would require NASA to not only look at the contractor but also “any other commercial or non-commercial entity related through ownership, control, or other affiliation to such entity.” For example, while SpaceX does no business with China, it is run by Elon Musk, who also leads electric vehicle company Tesla, which does have growing operations in China.

Bridenstine, asked about this at that hearing, suggested other organizations would be better positioned to review such issues. One example is the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), which reviews foreign investments in American companies.

“What we have to do as an agency is make sure that we don’t put ourselves in the role of CFIUS, or we don’t put ourselves in the role of the Department of Justice or the FBI. We have to be really careful that we do the things that we are good at, like getting to the Moon and on to Mars,” he told Gardner.

Former NASA administrator Sean O’Keefe (center) at a 2018 CSIS event with current administrator Jim Bridenstine (left) and former administrator Charlie Bolden. (credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky) |

Pace of exploration

During the webinar, Goldin made clear he was concerned about China’s space ambitions. “China is moving at the speed of light,” he argued. “If NASA continues on this very, very carefully planned program, we are going to fall way behind.”

One can debate how quickly China is moving in space; for example, its last crewed space mission was launched almost exactly four years ago, and its pace of activity has fallen far short of past predictions (see “Review: China in Space”, The Space Review, September 28, 2020). His comments, though, appeared to be more a criticism of the slow pace of NASA’s efforts.

“We landed on the Moon in July of 1969, and it’s damn time for America to get people out of Earth orbit,” he said. “Love the Moon, but we’ve got to start mining asteroids, we’ve got to start getting to other planets, we’ve got to start getting to moons of other planets.”

That would seem to be a dig at his successors, although Goldin blamed neither of his fellow panelists. “It shouldn’t have taken so long for Charlie to do what he had to do. It shouldn’t have taken so long for Sean, but there wasn’t the external pressure.”

O’Keefe, who led NASA when President George W. Bush announced the Vision for Space Exploration, saw things going pretty much as was planned back in 2004, despite the various twists and turns along the way. “I think the entire objectives that were laid out by President Bush and his Vision for Space Exploration is exactly what we’ve seen come to pass in the last 15 years,” he said.

He cited as evidence of that the successes of the commercial cargo and crew programs, and a renewed focus on a human return to the Moon as a stepping stone for later human missions to Mars. “It was all about developing the technologies in order to provide the means to explore deeper into space,” he said.

| “Once we get off the planet, we need to go places fast, and the only way to do that is nuclear propulsion,” Bolden said. |

The Vision for Space Exploration, though, was largely discarded by the Obama Administration, which rejected the goal of a human return to the Moon, only to have that goal reinstated, and then accelerated, by the Trump Administration. The original Vision for Space Exploration sought to return humans to the Moon by 2020, while NASA is now working towards a 2024 return.

“They’re all chapters, they’re all episodes, in what is really a continuum” of support, he argued, including from Congress. “Is it easy? No. Is it something that is enjoyable to do? Absolutely not. I’d rather have a root canal than ever testify again.”

That’s led, he concluded, “to elements of a consistent, sustainable kind of strategy over the course of the last couple of decades that really is pretty close to where it is we wanted to be and what we wanted to do.”

Space nuclear power

One example of that is the support for nuclear power and propulsion technologies, which has gone up and down over the last two decades. When O’Keefe was administrator, NASA was pursuing Project Prometheus, which sought to develop those technology and demonstrate them on a massive flagship mission to Jupiter (see “Space science gets big at NASA”, The Space Review, July 7, 2003).

“That’s been developed now to a much higher extent, but nowhere near as quickly as what we needed to in order to see some significant changes over the course of the last 15 years,” he said. “But we are at a better place now than where we were in terms of developing that technology.”

After O’Keefe left NASA, Prometheus was shelved as the agency focused more on the Constellation program to return humans to the Moon, an effort which did not require nuclear technologies. However, there has been renewed support, driven in large part by Congress, on developing nuclear power and propulsion technologies, such as the Kilopower nuclear surface reactor project by NASA and the Department of Energy and technology development of nuclear thermal propulsion.

All three former administrators endorsed development of nuclear propulsion in particular. “We’ve been using the same damn rocket technology since Apollo. It’s time to grow up and say the magic term, ‘nuclear.’ There, I said it,” Goldin said. “If America intends to be a world leader, we’ve got to grow up and learn how to live with nuclear.”

“Once we get off the planet, we need to go places fast, and the only way to do that is nuclear propulsion,” Bolden said.

Without such propulsion, O’Keefe said, “we’re going to be constantly limited by the time and distance challenges” of spaceflight.

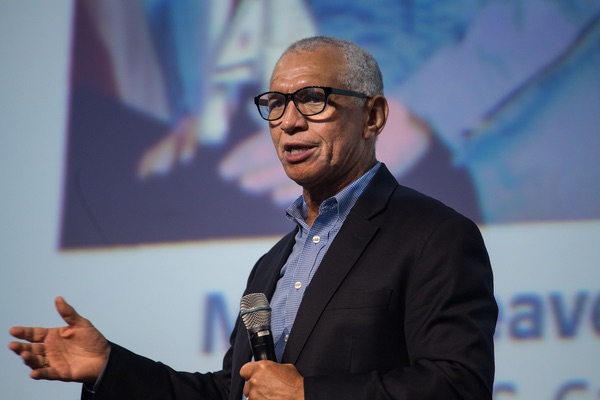

Former NASA administrator Dan Goldin, speaking at a 2010 symposium, said at the webinar he supports commercial spaceflight “as long as it’s commercial.” (credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls) |

Commercial spaceflight

One of the biggest trends in spaceflight has been the growing role of the private sector, particularly in human spaceflight. The successful SpaceX Demo-2 commercial crew mission to the ISS this summer fulfilled the goal of a program started when Bolden was administrator, and with roots that go back much deeper.

Commercial crew, Bolden recalled, was a much more difficult program to win support for than commercial cargo. “It fell victim to a couple of things. One was it had Obama’s name on it,” he recalled, arguing that led to funding shortfalls that pushed out the program by about four years.

Another was the perception that commercial crew was closely tied to SpaceX. “Nobody liked SpaceX, to be quite honest, on the Hill. They were an unknown quantity. They were the champions of space ideologues, or commercial ideologues,” he said.

What saved commercial crew, he believes, was the participation of Boeing, a mainstream space company. “If Boeing had chosen to stay out of commercial crew, we probably would have never gotten funding for it,” he said.

With Boeing involved, the next battle was making sure it was not the only company in the program. “Our big battle was convincing members of Congress that we had to have at least two providers,” he said. That turned out to be a wise decision, given the delays Boeing has experiences in development of its CST-100 Starliner.

Those vehicles will carry not just astronauts but also private spaceflight participants to the space station. Nearly two decades ago, Dennis Tito became the first space tourist to visit the station, flying on a Soyuz spacecraft over the vehement objections of Goldin.

| “I am all for commercial spaceflight, as long as it’s commercial,” Goldin said. “Ultimately, the revenue can’t come from the US government.” |

Goldin said his objection to Tito’s flight had nothing to do with commercial spaceflight but that his concern that it would interfere with the installation of the station’s robotic arm, which took place around the same time. (How Tito’s presence would interfere with that work wasn’t clear.) He lobbied both Tito and Yuri Koptev, head of the Russian space agency, to not fly on that mission.

“I used profanities” in a call with Koptev, he recalled, “and I told him if that damn Soyuz vehicle came near to the space station while we were performing this operation just because Dennis Tito wanted it, there was going to be major problems between the US and Russia.”

“I am all for commercial spaceflight, as long as it’s commercial,” he added. “Ultimately, the revenue can’t come from the US government. If it’s going to be commercial, it has to be providing goods and services outside of the domain of the US government.”

Bolden agreed. In his early years as administrator, he recalled, “the commercial ideologues were dominant” in the administration. But over time, he said he’s become more confident of the capabilities of commercial providers. “It’s okay for NASA to be an anchor tenant” for those service, he said. “NASA is about the only space agency in the world that has to go out and try to help the commercial sector, and I think we have done that.”

He’s still a little skeptical, though, about the business case for commercial spaceflight. He credited Boeing’s participation in commercial crew, a “program whose business case didn’t close back then. And, I’ll be blunt, I don’t know if the business case closes today.” (Bolden today is a consultant for Axiom Space, a commercial human spaceflight company.)

“Closing a business case for commercial human spaceflight is hard to make,” he said, “but it’s something that we cannot not do.”

The role of the ISS

Much of that commercial spaceflight activity revolves around the ISS, a program that played a central role in all three men’s tenures at NASA. Both Goldin and Bolden (who, for a year in the early 1990s, was assigned to NASA Headquarters while still part of the astronaut corps) discussed the 1993 House vote that rejected a proposal to cancel the station by a single vote, cast by Rep. John Lewis (D-GA), who passed away earlier this year.

Goldin recalled making a last-second pitch for the program as Lewis approached the House floor. “I jumped in front of John Lewis and started making my 15-second elevator pitch about how the future of America’s space program lies in your hands,” he said. “He broke out laughing, tears were coming down his cheeks, he thought it was so funny.”

| “I’m still holding out hope that, one of these days, the International Space Station will be recognized for the Nobel Peace Prize,” said Bolden. |

“After I made I my pitch, I said, ‘How are you going to vote?’ And he said, ‘I ain’t telling you,’” he continued. When Lewis voted in favor of the station, “we let out a shriek.”

The ISS has now become a symbol of perseverance and cooperation in spaceflight as it approaches the 20th anniversary of continuous human occupation at the end of this month. “The capacity to live and work in space for a continuous span of damn near 20 years is a remarkable achievement,” O’Keefe said.

“What we did with the International Space Station over the 20 years is giving people hope for peace,” Bolden said, despite the strained state of US-Russian relations in recent years. “I’m still holding out hope that, one of these days, the International Space Station will be recognized for the Nobel Peace Prize.”

“Amen, Charlie,” Goldin said.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.