Redundancy now, or redundancy never?by Jeff Foust

|

| Dynetics concluded that NASA “failed to consider the risks inherent in SpaceX’s technical approach and, more specifically, information too close at hand for NASA to ignore -- i.e., that four SpaceX Starships have exploded at various stages of their tests flights in recent months.” |

Both companies, in their protests, argued that NASA incorrectly evaluated their proposals. Blue Origin, for example, complained NASA improperly considered as weaknesses its lander’s guidance and communications systems, discussing those and other perceived oversights in great detail. “Because Blue Origin has shown its analysis does not contain the errors suggested by the Agency and, in fact, the Agency’s own independent analysis verifies Blue Origin’s results and proposal submission, the Agency’s assessment of a weakness is unreasonable, unsupported, and should be set aside,” it said after making its case about its lander’s communications links.

Dynetics argued in its protest that many of the elements of its lander design, like a crew cabin located close to the surface for ease of access, that were considered “significant strengths” in its proposal for its first HLS award (the “base period” awarded in April 2020) where now simply considered “strengths” in its Option A proposal, a downgrade the company said didn’t make sense. “In the end, Dynetics’ technical and management ratings cannot be squared with NASA’s prior evaluation of the same features of the proposal or with Dynetics’ performance on the Base period,” it stated. “The Dynetics design was not altered, only refined -- what must have changed were NASA’s technical and programmatic evaluation criteria.”

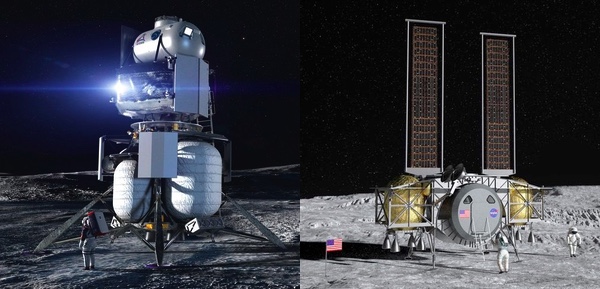

Both companies also criticized NASA for how it evaluated SpaceX’s proposal. Blue Origin, for example, wondered why it was given a weakness for having a crew hatch 10.2 meters above the surface, while SpaceX’s lander received a significant strength even those its hatch is three times higher—so high that SpaceX plans to use an elevator, rather than ladder, for astronauts to get down to the surface and back.

Dynetics concluded that NASA “failed to consider the risks inherent in SpaceX’s technical approach and, more specifically, information too close at hand for NASA to ignore -- i.e., that four SpaceX Starships have exploded at various stages of their tests flights in recent months.” (SpaceX did successfully land its latest Starship prototype a little more than a week after Dynetics filed its protest.)

The two companies did more, though, than simply argue that NASA improperly evaluated their proposals with respect to SpaceX. Both companies made the case that NASA erred by making just a single Option A award, rather than the two that had been widely anticipated. “NASA’s single award decision was inconsistent with NASA’s acquisition strategy and stated intent to promote competition (safety and reliability) by making two HLS Option A awards,” Blue Origin stated in its protest.

“In selecting SpaceX as the only Option A contractor in this second phase for the HLS program (and, consequently, for the last phase, as well), NASA has prematurely abandoned a core element of the acquisition strategy behind the HLS program -- i.e., ‘to create the most competitive environment practicable, maximizing the likelihood of successful development that will culminate in crewed demonstration missions,’” Dynetics wrote in its protest, quoting language from NASA’s source selection statement for the base period HLS awards in 2020.

NASA argued when it made the single award to SpaceX that, given its existing and projected budgets, it could not afford a second award. Blue Origin, which acknowledged in its protest that it submitted a bid valued at $5.99 billion, more than twice the $2.89 billion award to SpaceX, said it never had the opportunity to revise its proposal, and “would have welcomed the opportunity to offer specific adjustments in a revised proposal.”

| Blue Origin said it “would have welcomed the opportunity to offer specific adjustments in a revised proposal.” |

Blue Origin said that the combined value of its original bid and SpaceX’s winning bid, about $9 billion, was similar to what NASA spent on the overall commercial crew program, which supported Boeing and SpaceX. It also noted that, in a September 2020 document, NASA projected spending nearly $16.2 billion on the HLS program in fiscal years 2021 through 2025, far more than the combined value of the Blue Origin and SpaceX bids. (That plan, though, assumed NASA would get more than $3.2 billion in 2021; it received instead only $850 million.)

Dynetics has not disclosed the value of its bid, which NASA described only as “significantly higher” than Blue Origin’s proposal. In its protest, Dynetics argued that when NASA encountered the mismatch between anticipated and actual funding levels, there was a wide range of options for the agency, from opening discussions with all the bidders to cancelling the solicitation entirely and starting over. Another option, it noted, was to use the available funding to make awards to all three companies using a contract line item in the proposal for “sustaining” lander studies, rather than the single Option A award.

The Senate weighs in

The protests are in the hands of the GAO, which has until August 4 to rule on them. NASA announced April 30 it was suspending work on the contract it made to SpaceX, citing those protests.

There is a Plan B, though, for those companies even if their protests are denied (as the vast majority are.) Last Wednesday, the Senate Commerce Committee marked up a series of bills, including the Endless Frontier Act, a bill that would authorize the creation of a new technology directorate at the National Science Foundation.

Committee members used the markup to propose dozens of amendments to the bill, many of which had little to do with the NSF. One of them, introduced with no public advance notice and passed by a voice vote with no debate by the committee, attached to the NSF bill a NASA authorization bill similar to one the Senate passed at the end of last year, but which the House did not take up.

One difference in this NASA authorization bill is a new provision calling for “competitiveness within the Human Landing System program.” It directs NASA, no later than 30 days after the bill becomes law, to have at least two companies under contracts to develop human lunar landers. It would also authorize $10.032 billion from fiscal years 2021 through 2026 for the HLS program. (That funding, though, would have to be appropriated separately, and on an annual basis.)

“We also set important policy for NASA, while authorizing the resources needed to protect against programmatic risks and make sure our missions are safe and successful,” Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-WA), chair of the committee, said in a statement after the markup session. That statement noted that, among other provisions, the bill would “require that NASA maintain competition by funding at least two commercial capabilities” in the HLS program.

| “We’re still a few steps away from being able to issue the LETS contract request for proposals,” Watson-Morgan said of the follow-on competition for lunar lander services. |

This was not the first time that Cantwell has spoken out about the need for competition in the HLS program. “I have to say I was surprised last week about the Human Landing System development contract,” she told Bill Nelson when he appeared before her committee last month regarding his nomination to be NASA administrator (see “A message of continuity from NASA’s next administrator,” The Space Review, April 26, 2021).

Nelson, at the hearing, assured Cantwell that there will be competition in the later phases of the HLS program, when NASA procures lunar landing services beyond the single mission included in the Option A award to SpaceX. “Those competitions will be there, as articulated by the deciding authority on this competition,” he said.

When NASA announced the Option A award last month, it said it would accelerate planning for those follow-on competitions under an effort now known as the Lunar Exploration Transportation Services (LETS) program. NASA says LETS will be a full-and-open competition, with the intent to pick multiple companies to provide lunar lander services for the later, “sustainable” phase of the Artemis program.

LETS, though, is still more than a year in the future. “We’re still a few steps away from being able to issue the LETS contract request for proposals,” Lisa Watson-Morgan, NASA HLS program manager, said in an April 29 statement issued the day after NASA released a request for information about LETS.

At a May 3 industry day, she described plans to first issue a broad agency announcement to fund risk reduction work for companies interested in pursuing LETS. Those awards, though, would be small: about $15 million each, lasting 7 to 12 months. “We don’t have a tremendous amount of flexibility on funding,” she said. “That’s why we’re messaging the max would be $15 million, we believe, and we can only award probably a few.”

The later LETS awards, she said, may include some design, development, testing and evaluation support to allow NASA to certify the vehicles, but the implication for many in the industry is that any company that doesn’t have an HLS award—anyone other than SpaceX, right now—would be at a disadvantage. “Two years from now, other than billionaires who can choose to keep things around, you’re not going to have others left in the game that are going to give you real competition,” said one industry source.

Both Blue Origin and Dynetics warned of allowing only SpaceX to have an HLS contract. Blue Origin noted in its protest that NASA’s current approach “creates a potential monopoly for all future NASA exploration missions because there would not be continuing programs for lunar access other than the SpaceX solution and this could preclude an alternative solution in the future.”

“It follows that NASA must inevitably select SpaceX -- if anyone -- for any future lunar space transportation services between Gateway and the lunar surface that NASA intends to procure for the next ten years plus,” Dynetics claimed in its protest.

Cantwell, at Nelson’s confirmation hearing last month, effectively made the same argument. “I think there needs to be redundancy, and it has to be clear in this process that it can’t be redundancy later. It has to be redundancy now,” she said.

Supporters of a second HLS Option A award point to the benefits that competition provided for the commercial cargo and crew programs, including keeping prices down and offering the redundancy that Cantwell desired to allow the program to proceed if one provider suffers delays or a failure. The benefits of that redundancy are clear: the space station was able to keep operating after both Dragon and Cygnus cargo spacecraft were lost in launch failures, and NASA has all but ended its reliance on Soyuz thanks to Crew Dragon, even as Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner suffered development delays.

Yet, despite the benefits of redundancy, it’s lacking in much of the Artemis program. While some seek a second lunar lander provider, NASA has only one vehicle for transporting astronauts to lunar orbit—Orion—and only one launch vehicle that can launch Orion, the Space Launch System. There is also only one Gateway, but it’s not clear it’s essential to Artemis; at least the first mission will have the option of Orion docking directly with the lunar lander, rather that meeting at the Gateway.

| With NASA projecting just one Artemis mission a year through the late 2020s, that’s not much business for one lunar lander company, let alone two. |

The effects of the lack of redundancy in SLS and Orion is clear from the delays in the first mission, which has slipped from 2017 until at least late this year (and may slip again to 2022.) A second system might have provided NASA with that redundancy that some desire for HLS to mitigate delays. But ask Congress for a second heavy-lift launcher and crew vehicle and… well, good luck. When then-NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine suggested in 2019 that the Artemis 1 mission might use a vehicle other than SLS, like the Delta IV Heavy and Falcon Heavy, to launch an uncrewed Orion, the reaction from SLS supporters in Congress was strong enough that NASA backtracked within days and soon dropped any thought of launching Orion on anything other than SLS. (One wonders if a factor in selecting Starship was to give NASA redundancy of sorts for SLS/Orion, since the system, in theory, would also be able to launch astronauts and transport them from the Earth to the Moon as well as land them on the surface.)

Another aspect of the commercial cargo and crew programs is the expectation that NASA will be just one of multiple customers. That’s had a mixed track record as well. In commercial cargo, the award to SpaceX provided the Falcon 9 with the anchor tenant the company needed; that vehicle has gone on to be one of the most successful commercial launch vehicles ever. The cargo Dragon never won any business outside of NASA—SpaceX advertised free-flyer “Dragon Lab” missions but none ever flew—but it gave the company experience essential to its success in commercial crew, where it’s now finding commercial customers like Axiom Space.

Northrop Grumman and its corporate predecessors (Orbital ATK and, before that, Orbital Sciences) have marked the Antares rocket it developed for the commercial cargo program, but have yet to win any business for it. Cygnus, though, has helped the company win other business, including the HALO module for the lunar Gateway and, ironically, the transfer module for Blue Origin’s lunar lander. Boeing has also talked about commercial customers for Starliner, but it’s too soon to tell when those will emerge since the vehicle remains in development.

It's unclear, though, what sort of business will exist for the foreseeable future for commercial human lunar landers. If Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa is willing to buy a Starship flight around the Moon, perhaps there is another billionaire or two willing to pay for a trip to the surface, but that market remains highly speculative. A wealthy country like the UAE might be interested in such a flight, but such “sovereign clients” have long been a target for commercial orbital human spaceflight but have yet to emerge, even at far lower price points than a trip to the Moon.

It’s reasonable to assume, though, that for much of the next decade NASA will be the primary, if not only, customer for commercial human lunar landers. And with NASA projecting just one Artemis mission a year through the late 2020s, that’s not much business for one company, let alone two. Redundancy has its benefits, but it comes at a cost.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.