Scrutinizing the Russian-Iranian satellite dealby Bart Hendrickx

|

| Whatever Putin really meant to say, the existence of the Russian-Iranian remote sensing satellite project has been a well-established fact for several years. |

With a resolution of 1.2 meters, the imagery would fall far short of the quality achieved by US spy satellites or high-end commercial satellite imagery providers, but would far exceed the capabilities of a cubesat-sized indigenous Iranian observation satellite dubbed Noor-1, launched by a domestically built rocket in April 2020. The sources told the Post the launch could happen within months.[1]

One day after the story appeared, Russian President Vladimir Putin was asked to react to it in an interview with NBC. His reply (as translated by NBC) was rather confusing: “It’s just fake news. At the very least, I don’t know anything about this kind of thing. Those who are speaking about it probably will know more about it. It’s just nonsense, garbage.”[2] It is not entirely clear from this if Putin was denying the very existence of the satellite deal, dismissing the so-called “advanced capabilities” of the satellite, or trying to tell that he was simply not aware of the deal.

Earlier news reports

Whatever Putin really meant to say, the existence of the Russian-Iranian remote sensing satellite project has been a well-established fact for several years. As noted by the Washington Post, Russia and Iran publicly disclosed their intention to embark on this joint program back in 2015. The Post quoted an article published by Iran’s Press TV news service, which listed the Russian partners as NPK Barl, a manufacturer of satellite ground support systems, and VNIIEM (All-Russian Scientific Research Institute of Electromechanics), a builder of meteorological and remote sensing satellites. They would team up with the Iranian state-operated trade company Bonyan Danesh Shargh and the Iranian Space Agency.

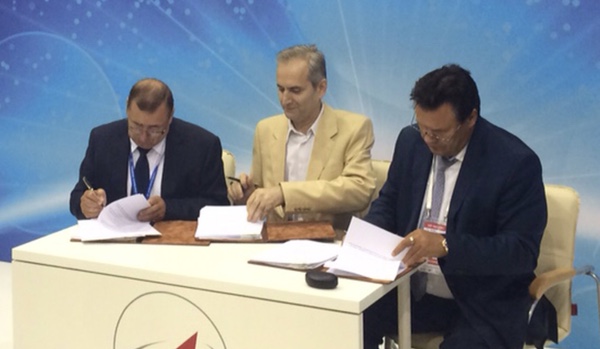

What the Press TV article was referring to was the signing of a pre-contractual agreement between the three parties that took place on August 25, 2015, at the bi-annual MAKS aerospace show in Zhukovskiy outside Moscow. The signing ceremony was also widely covered in the Russian media at the time. NPK Barl, which was given the lead role in the project, would be responsible for integrating and finishing the ground-based infrastructure, VNIIEM would build the satellite, while Bonyan Danesh Shargh would act as the satellite operator. VNIIEM’s director Leonid Makridenko was quoted as saying that the satellite would be a modified version of the company’s Kanopus-V satellite and ride as a co-passenger on a Soyuz launch vehicle.[3]

| In May 2018, NPK Barl and several other Russian companies were placed on the US State Department’s sanctions list for their alleged violation of the rules on the non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. |

The project occasionally re-appeared in Russian and Iranian news reports in the following three years. In February 2016, Makridenko expressed hope that the contract would be signed before the middle of April, in which case the satellite could be launched by a Soyuz rocket in late 2018.[4] The project was again discussed in July 2016 during a visit to Moscow by Iran’s Minister for Telecommunications and Information Technology Mahmoud Vaezi, who told the Mehr news agency that Iran was still negotiating “a suitable price” with Roscosmos for what he called Iran’s National Remote Sensing Satellite and expected that it would take two years to build it.[5] A final deal had still not been reached in April 2017, when Makridenko told the State Duma (Russia’s lower house of parliament) that the terms of the contract were still being negotiated.[6]

In May 2018, NPK Barl and several other Russian companies were placed on the US State Department’s sanctions list for their alleged violation of the rules on the non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. When asked for a reaction, NPK Barl’s press service said it was unclear what had motivated the US decision because none of the company’s contracts with foreign partners had anything to do with the development of military technology. Some Russian news outlets speculated it was because of NPK Barl’s leading role in the Iranian satellite deal or its possible involvement in North Korea’s space program.[7]

Project 505 unraveled

Nothing more was heard of the Russian-Iranian satellite deal afterwards, raising the question if a contract had actually been signed. The status of the project finally became clear last February during a virtual roundtable discussion on the future of Russia’s commercial space activities organized by the Federation Council, Russia’s upper house of parliament.

One of the speakers was Valeriy Labutin, introduced as the “general designer” of NPK Barl. During his presentation, Labutin revealed that his company would conduct the first launch of a Russian commercial remote sensing satellite “for a foreign customer” in the second quarter of this year, more specifically the summer. “All the infrastructure has been deployed, all tests have been completed and we’re ready to launch the satellite this year”, he said, without disclosing the identity of the customer.

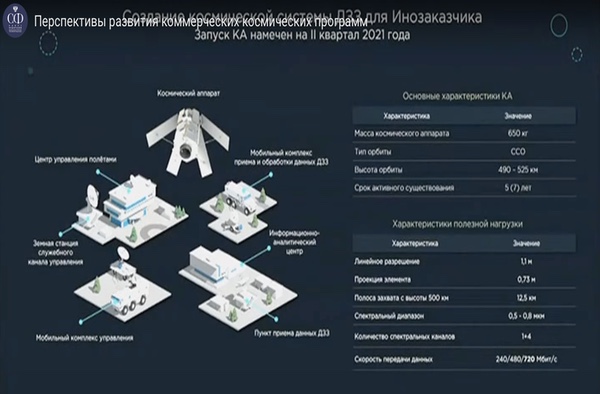

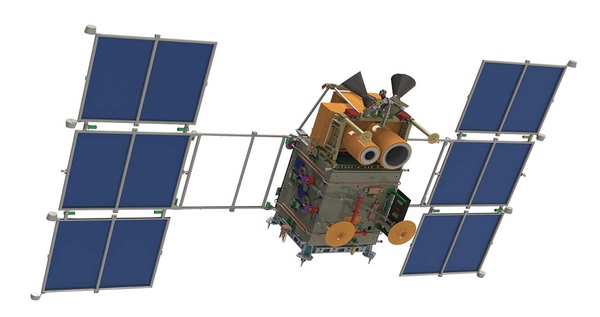

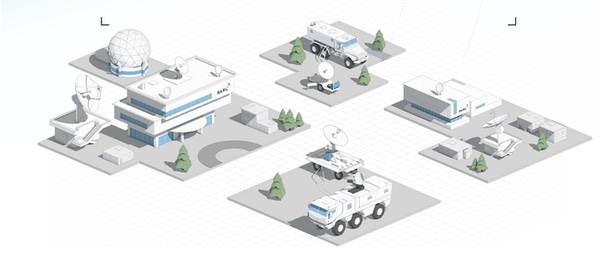

Labutin went on to say that the 650-kilogram satellite will have a linear resolution of 1.1 meters, adding that by Western standards the resolution actually is 0.73 meters. It is supposed to have an active lifetime of five years, which can be extended to seven years. Additional details can be seen in a slide shown during the presentation. The satellite, outfitted with four solar panels, will be placed into a sun-synchronous orbit with a perigee of 490 kilometers and apogee of 525 kilometers, and will cover a ground swath of 12.5 kilometers from an altitude of 500 kilometers. It can take pictures in spectral bands from 0.5 to 0.8 microns and send down data at speeds of 240, 480 and 720 megabits per second. Also seen is the satellite’s ground-based segment, which consists of both stationary and mobile flight control and data reception and processing centers.

Commercial remote sensing satellite “for a foreign customer” and related ground-based infrastructure as seen in a presentation by NPK Barl. (Source) |

Labutin subsequently also announced plans for a constellation of observation satellites called Arktika-KN (not to be confused with NPO Lavochkin’s Arktika-M satellite launched last February) that will use the same platform as the commercial satellite, but will carry a combination of radar, optical, and infrared payloads, the latter two offering a resolution of 40 and 60 meters. This system was also described in a patent published by NPK Barl earlier this year.[8] It is supposed to be deployed beginning in 2024, but appears to be intended only for domestic purposes.

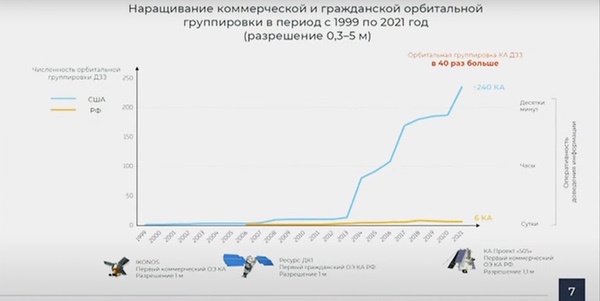

Also appearing at the Federation Council meeting was Sergei Baskov, who for some reason was introduced only as “a full member of the Russian Federation of Cosmonautics” although he is also NPK Barl’s general director. Baskov confirmed that the first Russian commercial electro-optical imaging satellite is scheduled for launch this year, without giving further details. The satellite did appear in one of the slides he presented. It looks identical to the one shown in Labutin’s presentation, also has a resolution of 1.1 meters and is described as belonging to “Project 505”.[9]

The “Project 505” satellite is seen in the lower right of this slide shown by NPK Barl director Sergei Baskov. (Source) |

The two presentations were newsworthy enough to feature in a number of Russian news reports, but none of those made the obvious connection with the earlier reported Russian-Iranian satellite deal.[10] This must have been either out of ignorance or prudence, considering the politically sensitive nature of the satellite deal. It wasn’t until after the publication of the Washington Post article that some Russian reports linked Labutin’s presentation to the satellite for Iran.[11] There can indeed be little doubt that this is the satellite Labutin and Baskov were talking about. The fact alone that they did not identify the foreign customer is telling enough in itself. Moreover, NPK Barl is not known to have concluded satellite deals with any other foreign partners than Iran and, as can be determined from a number of other sources, the Project 505 satellite is a product of VNIIEM, NPK Barl’s Russian partner in the project.

| When the preliminary agreement on the Russian-Iranian satellite was signed in August 2015, VNIIEM’s director Makridenko said it would be based on the Kanopus-V satellite. However, Kanopus-V looks significantly different from the Project 505 satellite seen in the NPK Barl slides. |

Project 505 first appeared in the 2018 annual report of AO Novator, a company that provides components for VNIIEM satellites. The report mentioned Project 505 as one of several VNIIEM projects for which the company would manufacture components in 2019, more specifically antennas and a separation system, which could be a system to separate it from the launch vehicle or from other satellites carried by the same rocket. [12]

Project 505 was also the subject of a handful of contracts published on Russia’s government procurement website in 2019. From these it could be learned that the Institute of Space Research (IKI) delivered star and Sun sensors (named mBOKZ-2R and OSD-V) to VNIIEM for the satellite’s attitude control system and that NIIEM (a company belonging to the VNIIEM Corporation) placed an order with a German company to provide space-qualified stepper motors needed to adjust the satellite’s optical payload.[13]

Platform, payload, and ground segment

When the preliminary agreement on the Russian-Iranian satellite was signed in August 2015, VNIIEM’s director Makridenko said it would be based on the Kanopus-V satellite. This is possibly also why the Washington Post’s sources assume the satellite must be of that type. However, Kanopus-V looks significantly different from the Project 505 satellite seen in the NPK Barl slides. It is a 470-kilogram satellite that has a different platform with two solar panels extending from either side of the satellite. It also has a payload with a relatively low ground resolution (2.5 and 12 meters for panchromatic and multispectral imagery, respectively).

Six of the satellites (including one adapted for infrared observations) were launched between 2012 and 2018 and an identical one was launched for Belarus under the name BKA in 2012 (this, in fact, was the first remote sensing satellite manufactured by Russia for another nation, with another one, Egyptsat-2, built by RKK Energiya for Egypt, following in 2014.) If the satellite seen in the NPK Barl slides is indeed the one for Iran, then it is not of the Kanopus-V type. There was possibly a decision to switch to a different bus in the course of its development.

Kanopus-V. (Source) |

A satellite seen on NPK Barl’s website is named Alpha-ES and described as an advanced high-resolution Earth remote sensing satellite. It has a multispectral (red, green, blue, and near-infrared) imaging system with a maximum resolution of 0.7 meters from an altitude of 600 kilometers. However, its reported mass (300 kilogram) is less than half that given for the Project 505 satellite and it has three rather than four solar panels.[14]

Alpha-ES satellite seen on NPK Barl’s website. (Source) |

One possibility is that the Project 505 satellite employs the same platform as Razbeg, a small military imaging satellite that VNIIEM is developing under a contract awarded by the Ministry of Defense in November 2016 and which is presumably intended to complement imagery provided by bigger, higher-resolution spy satellites.[15] The Institute of Space Research is known to have supplied exactly the same star sensors for Razbeg as for the Project 505 satellite, but that is not necessarily indicative of a common design.[16]

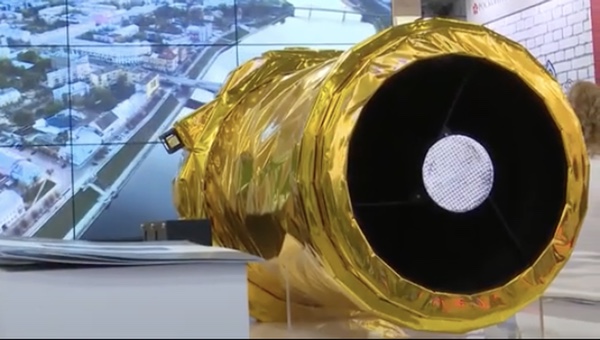

It is not clear from the available information who exactly built the optical payload for the Project 505 satellite. VNIIEM builds only satellite platforms, not payloads, and NPK Barl was said to be responsible only for the ground segment. However, the company seems to have branched out into optical systems as well. At an exhibition in February 2019, it presented a remote sensing telescope that weighs just 46 kilograms and, in the words of director Sergei Baskov, has the same performance as space-based telescopes weighing more than two tons. A Russian TV report on the exhibition said it would be launched in 2021, without mentioning the host satellite.[17]

Lightweight remote sensing telescope presented by NPK Barl in early 2019. (Source) |

The official ground resolution of the Project 505 satellite is 1.1 meters, but as noted by Valeriy Labutin in his presentation, it would be considered 0.73 meters when applying the Western criterion to assess an observation satellite’s resolution. That is the so-called ground sample distance, which is the distance between the centers of two consecutive pixels measured on the ground. One Russian technical study two years ago concluded that this criterion results in overestimating what it called “the real instrumental resolution” of satellites. According to the authors, only four out of ten Western-built commercial remote sensing satellites officially claimed to have submeter resolution really have that capability (WorldView-1, WorldView-2, WorldView-3, and GeoEye-1).[18]

| Whether that launch will really take place this year, as claimed by the NPK Barl officials last February, remains to be seen. |

As seen in the slide shown during Labutin’s presentation, the Project 505 satellite will be supported by a network of stationary and mobile mission control centers as well as data reception and processing centers. The production of this highly automated ground support hardware seems to have been Barl’s core business since it was founded in 1997 (although the company was not officially registered until 2004.)[19] Labutin said that in the past ten years alone, NPK Barl has supplied 23 stationary and mobile remote sensing units to both Russian and foreign customers, with 15 more scheduled for delivery before 2025. A patent published by the company in 2012 described the mobile data reception and processing units (named TRITON) as an improved version of the US Air Force’s Eagle Vision system, a collection of deployable satellite downlink stations that process commercial satellite imagery.[20] Obviously, such mobile remote sensing units would come in handy for military commanders in the field.

NPK Barl’s satellite ground segment: stationary and mobile satellite control centers in the lower and upper left and mobile and stationary data reception and processing centers in the lower and upper right. (Source) |

NPK Barl’s armored mobile satellite control unit. (Source) |

According to the Washington Post article, Russian experts traveled to Iran this spring to help train ground crews that would operate the satellite from a newly built facility near the northern Iranian city of Karaj. Most likely, the facility was built with Barl’s assistance. Actually, Barl seems to have delivered such equipment to Iran even before the joint satellite project got underway in earnest. In October 2015, a Russian newspaper reported that the company had helped Iran construct two ground stations for remote sensing satellites “in the region of the Persian Gulf.” Barl had provided both hardware and software that would make it possible to quickly obtain end products with minimal human intervention. The two stations had reportedly already entered service by that time.[21] This was just two months after the signing of the initial agreement on the joint satellite project, which makes it unlikely that this construction work was part of Project 505. Still, this doesn’t rule out the possibility that these same stations will be used to receive data from the satellite once it reaches orbit.

Whether that launch will really take place this year, as claimed by the NPK Barl officials last February, remains to be seen. According to the plans announced in 2015, the satellite would be launched as a co-passenger on a Soyuz-class launch vehicle, but there do not appear to be any available slots for it on launches planned later this year. It is also possible that the Russians have since shied away from launching the satellite together with civilian satellites, which would force them to show it to the outside world. A possible alternative would be for the satellite to hitch a ride to space with military payloads scheduled for launch on two Angara-1.2 rockets from the Plesetsk cosmodrome this year and next.

Like many other Russian-built satellites, the Project 505 satellite may also be experiencing delays that are a direct result of the Western economic sanctions imposed on Russia. Roscosmos chief Dmitriy Rogozin recently acknowledged that dozens of Russian satellites are currently grounded because not enough foreign-built electronic parts are available to finish their construction.[22] Russia’s launch statistics for this year only confirm this. The country has so far conducted just eight space launches, only four of which carried domestically built payloads.

At any rate, analysis of recent Russian sources confirms the Washington Post story that the Russian-Iranian remote sensing satellite is very real and probably only months away from launch. It also suggests that the satellite uses another platform than Kanopus-V and may be more capable than earlier believed when applying Western standards for determining its ground resolution.

References

- J. Warrick, “Russia is preparing to supply Iran with an advanced satellite system that will boost Tehran’s ability to surveil military targets, officials say”, Washington Post, June 11, 2021.

- NBC interview with Vladimir Putin, June 12, 2021.

- See for instance: TASS report (in Russian), VNIIEM press release (in Russian), August 25, 2015.

- RIA Novosti report (in Russian), February 24, 2016.

- Mehr news agency reports, July 31, 2016 and August 6, 2016.

- RNS news agency report (in Russian), April 14, 2017.

- Articles (in Russian) published in RBK and Kommersant, May 10, 2018.

- Patent (English machine translation) published by NPK Barl in April 2021.

- Video of a Federation Council roundtable discussion on Russia’s commercial space program (in Russian), February 15, 2021 (Baskov presentation: 7:35-16:00, Labutin presentation: 51:00-1:03:00).

- See for instance: TASS report (in Russian), February 15, 2021 ; Article (in Russian) in Vzglyad, February 15, 2021.

- Article (in Russian) in Vzglyad, June 11, 2021.

- AO Novator’s annual report (in Russian) for 2018.

- Procurement documentation (in Russian) related to the star and Sun sensors published in September 2019, October 2019, November 2019 and December 2019 ; Procurement documentation related to the stepper motors published in December 2019.

- NPK Barl website (in English).

- B. Hendrickx, “Upgrading Russia’s fleet of optical reconnaissance satellites”, The Space Review, August 10, 2020.

- Procurement documentation (in Russian) related to star sensors for Razbeg published in July 2019 and November 2019.

- Television report (in Russian) on the RIF-2019 exhibition held in Tver, February 21, 2019.

- Article (in Russian, with English abstract) published in “Informatsia i kosmos”, 1/2019.

- Brief history of NPK Barl (in Russian) published on the occasion of the Armiya-2017 exhibition.

- Patent (English machine translation) published by NPK Barl in 2012.

- Article (in Russian) published in Voyenno-promyshlennyy kuryer, October 21-27, 2015.

- RIA Novosti report (in Russian), June 7, 2021 ; Interview with Rogozin (in Russian) by the Rossiya-24 TV network, June 15, 2021.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.