Review: Across the Airless Wildsby Jeff Foust

|

| They drove the scale model of the rover into the office of center director Wernher von Braun. The unorthodox sales pitch worked. “We must do this!” von Braun exclaimed at the end of the meeting. |

GM executives mentioned, only in passing, that this is not the first time the company has been involved with lunar rovers. Fifty years ago this month, Apollo 15 landed on the Moon. Unlike the three previous landings, where astronauts were limited to locations they could reach on foot, astronauts David Scott and James Irwin had a “moon buggy” that allowed them to travel far greater distances, increasing the science they could perform. Boeing was the prime contractor for that rover, with GM as a key partner.

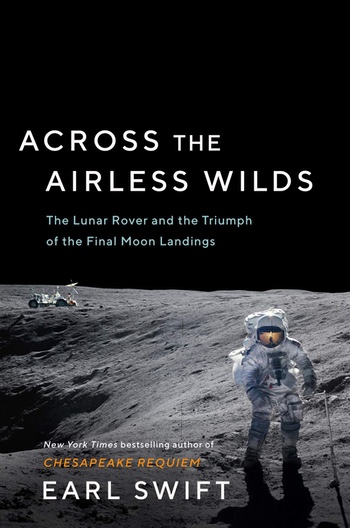

The development of what NASA formally called the Lunar Roving Vehicle is the subject of Earl Swift’s fascinating book Across the Airless Wilds. In retrospect, both the utility of a lunar rover and the specific design of the one used on the final three Apollo landings seems straightforward. However, it took years of effort to both win over NASA about including a rover on Apollo missions and to develop the vehicle that astronauts drove across the lunar terrain.

In the early years of the Space Age, it was clear that a rover of some kind, or some other source of mobility, would be useful for future human expeditions, but no consensus on what it should look like. Companies proposed a wide variety of designs, from wheels and treads to even a gas-powered pogo stick and a jetpack. One of those companies was GM, which had a research lab in California where a group that included M.G. “Greg” Bekker, the world’s leading expert in studying how vehicles can move across any terrain, worked on rover designs.

Much of that effort focused on either robotic rovers proposed but never flown on lunar missions like Surveyor or much larger crewed rovers that fell by the wayside as budget pressures narrowed NASA’s lunar ambitions. But some at GM persevered, including Sam Romano and Frank Pavlics, who wondered if it would be possible to fit a smaller rover in one of the storage areas of the Lunar Module. They developed a one-sixth model of a rover that could fold up in that storage area, then took it to the Marshall Space Flight Center. That model had a motor and could be driven by remote control, so they drove it into the office of center director Wernher von Braun. The unorthodox sales pitch worked. “We must do this!” von Braun exclaimed at the end of the meeting.

That meeting set the course for what would become the Lunar Roving Vehicle, but it did not guarantee that GM would build it. GM partnered with Boeing on its bid, going up against Bendix, Chrysler, and Grumman. At times in the evaluation both Bendix and Grumman appeared more likely to win, but in the end Boeing and GM won with a low bid (too low, as it turned out, as the project severely overrun its budget.)

| “If we went to the Moon today,” one engineer from the Apollo era said, “you could go with the same vehicle—don’t change a thing about it.” |

The development of the lunar rover was perhaps a classic example of a spaceflight project, with cost overruns, technical issues, and a vehicle struggling to stay within its mass budget. It was, after all, a “spacecraft on wheels,” as NASA’s project manager for the rover, Sonny Morea, put it, and while it looked like a car it would suffer the problems endemic to spacecraft. But, as in so many other projects, engineers overcame technical problems and cost pressures to deliver a rover.

And what a rover it was. The rover allowed the astronauts on the Apollo 15, 16, and 17 missions to travel much farther from the lander than if they could go on foot, and be less fatigued in the process since they were walking far less. Even with minor issues, like fenders over the wheels that came off, causing dust to spray everywhere (fixed, famously, on Apollo 17 with maps and clips) the astronauts enjoyed the rovers. Scientists did, too, since the rovers allowed astronauts to go to more locations and collect more samples.

The lunar rover project ended with Apollo, and it would be more than two decades before NASA flew any kind of rover again: Sojourner, the first of a series of Martian robotic rovers that have, in their own ways, demonstrated the importance of mobility on another world. Robotic rovers have returned to the Moon with the two Yutu rovers flown on China’s Chang’e-3 and 4 missions, with more to follow from NASA and others in the coming years.

And what about the future rovers that Artemis astronauts may one day drive? At the Lockheed-GM announcement in May, executives showed a conceptual illustration of a rover, but offered few details about what specific designs they’re considering. But some of those who worked on Apollo’s rover argue in the book that NASA would do well to simply brush off and update those designs for Artemis. “If we went to the Moon today,” one engineer from the Apollo era said, “you could go with the same vehicle—don’t change a thing about it.” The Lunar Roving Vehicle may be the ultimate classic car.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.