“Starship to orbit” ought to be a tipping point for policy makersby Doug Plata

|

| Starship will cause a turning point for humanity as we begin spreading beyond Earth. It is at the level of any of the great moments of exploration and settlement. |

But SpaceX is even positioned to have sufficient funding independent from NASA. Not only is Elon Musk often among wealthiest people in the world, but SpaceX is also able to raise very large amounts of funding for Starship development. If Starlink pans out as intended, SpaceX anticipates having annual revenue equal to the entire budget of NASA. Long gone are the days when SpaceX struggled to ensure its own financial survival. When a Starship crashes during development, no serious person questions whether SpaceX can continue. Even the existing production system can crank out more vehicles in a month or two, assuring no long delays in the test program due to setbacks. There’s always the next prototype nearing completion. It would seem that SpaceX can weather things even if the Starship development path going forward is challenging.

The significance of Starship

SpaceX is completely rewriting the book when it comes to rockets. A fully and rapidly reusable SHLV questions the competitiveness of almost all other rockets. Take, for example, SpaceX’s plan to place 400 Starlink satellites into orbit per launch in which most of the cost is only propellant. Who could compete with that? All the existing expendable rockets worldwide simply won’t be able to compete with Starship. And those companies or countries that seek to develop fully reusable rockets are years behind SpaceX and will find that SpaceX will have moved well forward by the time their competitors achieve full reusability. It’s hard to catch a target that is both ahead of you and accelerating away.

But there is an important historic significance to Starship as well. As noteworthy as the first woman and the first person of color on the Moon is, the real historic prize to be seized is the establishment of humanity’s first foothold off Earth. Starship will cause a turning point for humanity as we begin spreading beyond Earth. It is at the level of any of the great moments of exploration and settlement.

Levels of Starship success

Just because SpaceX intends to produce a fully and rapidly reusable SHLV doesn’t mean its success is inevitable. SpaceX may get Starship to orbit, but after bulking up with a heat shield and carrying that landing burn propellant, how much payload will it be able to get to orbit? It is a rather important question. If its payload to LEO is moderately below 100 metric tons then this affects how many propellant tanker launches will be needed to go beyond LEO. After a while it becomes excessive.

Yet, full reusability is not the only level of success that Starship can achieve. And even the most modest success questions the need for SLS. If Starship can reach orbit with sufficient payload, even without reuse of the Super Heavy booster and without reentry, landing, and reuse of Starship, it will still be a far more cost-effective SHLV than SLS. If Starship is also able to reach orbit and successfully retrieve its Super Heavy booster, this will make it dramatically more cost-effective than SLS. And if Starship achieves orbit, successfully retrieves its Super Heavy booster, and safely reenters and lands the Starship, then SLS becomes a strange historical footnote: terribly expensive, flew a few times, and then retired.

The issue of human rating

The only remaining valid argument for SLS is that it will probably achieve human rating for deep space missions before Starship achieves the same level of safety. If urgency is more important than sustainability, then perhaps there’s a case for continuing the development and use of SLS before Starship achieves human rating.

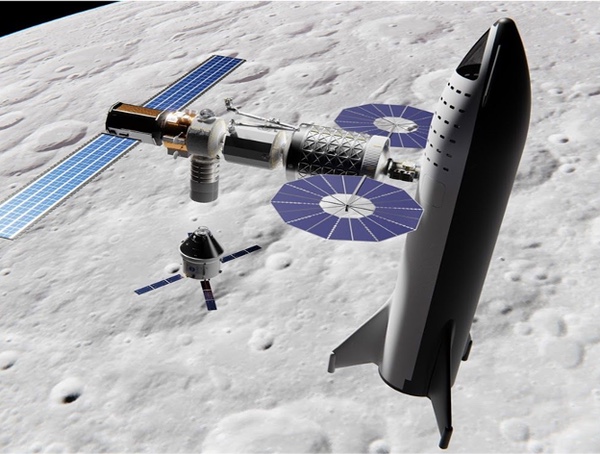

| If the Lunar Starship ever docks with Gateway, the size comparison with Gateway will appear silly and beg the question as to whether Gateway is actually necessary. |

But the SLS/Orion system is intended to send fewer astronauts to lunar orbit than could fit within a Dragon or Starliner capsule. And Orion can also get to LEO using different approaches than on an SLS, including on a Delta IV Heavy or Falcon Heavy. It will be interesting to see how the crew for the dearMoon mission are launched to orbit because the fastest and safest way of doing this would be to launch the crew on one or two Dragons and then transfer them over to Starship. If the Lunar Starship is safe enough to take astronauts from the Gateway to the lunar surface and back, wouldn’t it be safe enough to ferry astronauts between LEO and the Moon as well? If NASA was open-minded to all potential architectures, it could see how the same missions could be accomplished using SpaceX alone with equivalent safety and at far, far lower costs.

Human-rating Starship

SpaceX has experience with human rating vehicles (Falcon 9 and Dragon) and they are fully committed to developing Starship to the point where they can launch crew starting with the dearMoon mission slated for 2023. And of course, since SpaceX has a contract worth $2.9 billion to develop Starship to the point where they can ferry astronauts from the Gateway to the lunar surface and back, then wouldn’t it be safe to ferry astronauts from LEO to the Moon? And, when that point in time is reached, even if Starship isn’t yet human rated for the launch phase, there are safe ways of getting astronauts to LEO, namely, in a Dragon and/or Starliner capsule. So, one could easily envision an Earth-Moon architecture that doesn’t need SLS for heavy cargo, nor to launch the Orion capsule to LEO.

Size comparison of Starship, Gateway, and Orion. (credit: Mack Crawford) |

Awkward moments

There will be several moments which will prove awkward for NASA. First, when Starship deploys up to 400 Starlink satellites at a time, it will be clear that the heavy cargo capability of SLS can be provided by another system for pennies on the dollar.

Second, if the Lunar Starship ever docks with Gateway, the size comparison with Gateway will appear silly and beg the question as to whether Gateway is actually necessary. Does this even make sense? Couldn’t two Starships simply dock with each other and transfer propellant from one to another. Is there really a need for a middleman?

The third moment will be when SpaceX conducts private lunar flyby missions at dramatically less cost than what NASA is planning on spending for launching crew to the Gateway. The inevitable question that reporters and lawmakers will ask is, “Why not use the $3 billion a year spent on SLS and buy dozens of Starship launches?” Why indeed?

Finally, when two Starships dock with each other and transfer propellant, it will have a capability well beyond the SLS. I have spoken with aerospace engineers who work on cryogenic propellant transfer, who agree that it probably won’t be a particularly difficult achievement.

Expiration date on SLS

Here is the tentative timeline for the first three Artemis missions:

- Artemis 1 – no earlier than (NET) November 2021 - Uncrewed orbit of the Moon.

- Artemis 2 - NET September 2023 - Crewed lunar flyby.

- Artemis 3 - probably after 2024 - Crewed mission to the lunar surface, probably not going through the Gateway.

| So, what should the decision makers do once Starship achieves orbit? They should commit to fully utilizing Starship’s capabilities. |

So, what should the decision makers in Washington do when faced with the competing options of the expensive and old, but proven safety, of legacy hardware (i.e. the SLS) versus a much more cost-effective approach (i.e. Starship) that will, within a few years, provide similar levels of safety? At some point, it will be obvious that SLS is an unnecessarily expensive alternative to Starship. One might argue that a government SHLV is needed as a backup to the private Starship. But, given how many Starship flights could be purchased for just one SLS flight, that argument is ultimately untenable.

Will NASA risk its relevance?

For a very long time, NASA has been in the driver’s seat when it comes to the nation’s human spaceflight program—and it still is. But for how long? Depending on how successful Starship becomes, NASA could find itself in the awkward position of losing the leadership for both lunar and Martian human spaceflight. In this case, NASA would not be losing it to a competing country (aka China) but instead it would simply become irrelevant when countries and private individuals are able to purchase tickets directly from SpaceX. Sure, NASA could still do planetary probes and rovers, but to continue to lead in space, it needs to continue to play a leading role in human spaceflight.

What should the space policy decision makers do?

Given everything discussed above, space policy makers really ought to accept the reality of where things are headed. When Starship achieves orbit, then the handwriting is on the wall for SLS. The sooner that we begin the transition to Starship at the center of the nation’s human spaceflight program, the better.

The old adage says, “If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em.” So, what should the decision makers do once Starship achieves orbit? They should commit to fully utilizing Starship’s capabilities. NASA should do an evaluation of what vehicles are actually necessary. When allowed to do this in the past, they concluded that Falcon Heavy was sufficient for the Europa Clipper mission instead of SLS. They also concluded that Artemis 3 could bypass the Gateway and go directly to the Moon. At one point, former NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine even described a lunar surface architecture using a combination of Falcon Heavy and Delta IV.

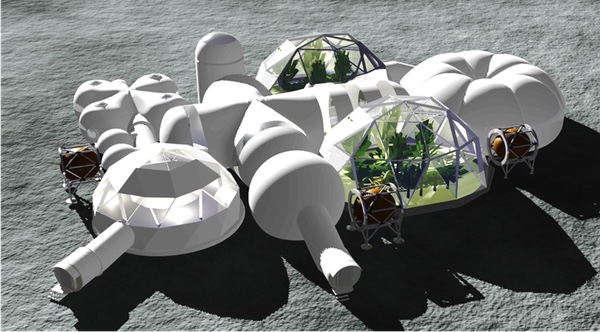

Illustration of the InstaBase – a fully inflatable initial base able to support an initial crew of eight. (credit: The Space Development Network) |

But the decision makers should also consider a dissimilar, redundant Earth-Moon transport system using hydrolox engines that can eventually utilize the lunar polar ice for propellant. Blue Origin is the logical company to do that. Given Starship’s anticipated capability (i.e. 100 tonnes of cargo or more than 100 passengers to the lunar surface), NASA’s limited, exploration orientation needs to give way to where that level of capability is leading: a large, international lunar base that can eventually become a settlement. Any competing Earth-Moon transport system needs to rise to that level of settlement capability and the decision makers should require that.

Surface systems

Frankly, SpaceX doesn’t need the full $2 billion per year that SLS gets. It’s making faster progress with less. But given that Starship is bringing a future with a large lunar base to our foreseeable future, NASA should really get going with completing surface systems to make sure that it is ready to fully utilize Starship’s capability as soon as it becomes available. We need to stop the endless study phases and instead funding work on of all sorts of alternate concepts. We need to act like we are facing a deadline (which we are) and choose a final surface architecture and develop it. As for habitats, we will quickly need very large habitats soon because Starship will be able to deliver perhaps a hundred residents at a time. An inflatable habitat massing 100 metric tons would have a footprint of about 21,000 sq. ft. (half an acre), not counting equipment to be shipped and installed later. We need to set aside the endless 3D-printing challenges for later and proceed with inflatables, a technology with three examples in space now. Lunar habitats and supporting infrastructure are a much better way to spend the $2 billion a year.

International leadership

The decision makers need to recognize that Starship will provide a remarkable foreign policy opportunity. Per-seat prices on a fully reusable Starship means that even relatively small countries could purchase a ticket for their national astronauts to explore the surface of the Moon on behalf of their own citizens and in their own language. If there is a growing international lunar base, many countries may want to participate.

| When Starship achieves orbit, that moment should cause them to fundamentally rethink our human spaceflight program and make decisions to take full advantage of this most remarkable opportunity. |

America should actively take the lead in opening up the Moon (and then Mars) to the nations of the world by encouraging national pride and leading in the development of an international lunar base in which freedom and liberty are the foundational principles as humanity starts to spread beyond Earth. The goodwill generated by this will be a tremendous foreign policy achievement. Given the number of countries that will be able to afford to send their astronauts, we need to have a much broader view of the Artemis Accords than the dozen countries signed up so far.

Conclusion

Starship really does change everything, not just for lunar exploration but for the next step for humanity. The decision makers in Washington need to accept where Starship is taking us. When Starship achieves orbit, that moment should cause them to fundamentally rethink our human spaceflight program and make decisions to take full advantage of this most remarkable opportunity.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.