The normalization of space tourismby Jeff Foust

|

| “I was overwhelmed with the experience, with the sensation of looking at death and looking at life and what’s become a cliché of how we need to take care of the planet,” Shatner said after his flight. |

Roscosmos provided few updates about the status of the filming during the 12-day stay on the station by Peresild and Shipenko. Late Saturday the two, along with Novitskiy, boarded the Soyuz MS-18 spacecraft and returned to Earth, landing in Kazakhstan. The usual post-landing activities of extracting the cosmonauts from the capsule and placing them in reclining chairs, attended to by doctors and other personnel, became a curious hybrid of reality and fantasy. Those real-life activities were being filmed for the movie, apparently requiring multiple takes at times.

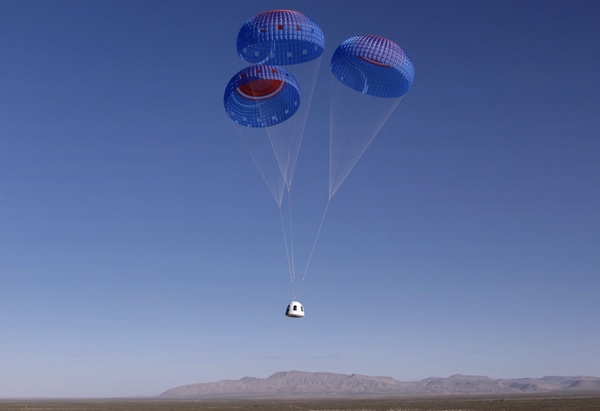

But most of the attention was on the world-famous actor in Blue Origin’s New Shepard suborbital vehicle. The man who became famous playing a starship captain, William Shatner, got to experience the real thing. He was one of four people on the NS-18 mission, traveling just above the Kármán line and getting several minutes of weightlessness and views of the Earth on Wednesday morning’s suborbital flight.

Safely back on the ground after his ten-minute mission, he offered a stream-of-consciousness assessment of the experience, nearly as long as the flight itself, to Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos next to the New Shepard capsule (see “Black ugliness and the covering of blue: William Shatner’s suborbital flight to ‘death’”, The Space Review, this issue.) He offered similar assessments in television interviews in the following days.

“I was overwhelmed with the experience, with the sensation of looking at death and looking at life and what’s become a cliché of how we need to take care of the planet,” he said on NBC’s “Today” program Thursday. “I was struck so profoundly by it.”

The largely positive publicity from the flight was welcomed by Blue Origin, no doubt. In late September, a group of 21 current and former employees, all but one of whom are anonymous, published an essay detailing a toxic workplace environment at the company, including claims of sexual harassment and “suppression of dissent” as well as environmental issues with the construction of its new headquarters building. That essay triggered a wave of follow-up pieces adding more weight to those claims.

Those concerns extended to spaceflight safety. “In the opinion of an engineer who has signed on to this essay, ‘Blue Origin has been lucky that nothing has happened so far,’” the stated, citing personnel “stretched beyond reasonable limits” working on New Shepard. “Many of this essay’s authors say they would not fly on a Blue Origin vehicle.”

Their concerns were linked to a push by company leadership to increase the flight rate of New Shepard: “their goal, routinely communicated to operations and maintenance staff, was to scale to more than 40” launches per year. “Some of us felt that with the resources and staff available, leadership’s race to launch at such a breakneck speed was seriously compromising flight safety.”

| “I do think we’re going to mint more new astronauts next year, in 2022, than any previous decade,” Taylor predicted. |

Blue Origin has a long way to go to reach 40 flights per year. Last week’s flight was the fifth New Shepard mission of the year, using two different vehicles. The company is expected to make, at most, one more launch before the end of the year, with plans for 2022 and beyond uncertain.

During the company’s webcast of the NS-18 mission, Blue Origin did not directly address the claims laid out in the essay, but offered what seemed like an extra emphasis on safety during prelaunch programming. “Safety has been baked into the design of New Shepard from day one,” said one of the webcast’s hosts, adding that the company conducted external reviews of the vehicle by people with “deep experience” in spaceflight programs before allowing people to fly on it. “Unanimously, this team determined that New Shepard met the highest standards for certification.”

As it turned out, the flight went off without any problems, other than unspecified issues during the countdown that delayed liftoff by more than an hour. The flight profile looked like the first crewed New Shepard flight in July, or even the payload-only flight in August using a different New Shepard booster and capsule (the company currently has two, one reserved for crewed flights and the other for research payload and other cargo.)

The flight was seemingly routine in more ways than one. It was the fifth mission in three months to carry private customers. In addition to NS-18, as well as the Russian filmmakers on the station, there were the flights of SpaceShipTwo and New Shepard in July and, in September, the Inspiration4 orbital mission on a Crew Dragon spacecraft. Seventeen of the last 18 first-time space travelers were on those flights; the eighteenth is Chinese astronaut Ye Guangfu, who launched Friday on the Shenzhou-13 mission.

The four people on New Shepard pose for a photo at apogee of their flight (from left): Glen de Vries, Audrey Powers, William Shatner, and Chris Boshuizen. (credit: Blue Origin) |

More missions are coming. Blue Origin may fly its next New Shepard crewed flight as soon as December, and it could be the first to carry a full complement of six people. Also in December will be Soyuz MS-20, a dedicated commercial Soyuz mission arranged by Space Adventures carrying Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa and his assistant, Yozo Hirano, along with Russian cosmonaut Alexander Misurkin on a 12-day mission to the ISS. In February, Axiom Space will launch its first mission to the ISS, Ax-1, carrying three customers and former NASA astronaut Michael López-Alegria on a Crew Dragon.

Those recent and upcoming missions have created the perception that space tourism has finally arrived—maybe a decade and a half late, given the optimism in the wake of the Ansari X Prize won 17 years ago this month, but here nonetheless. Virgin Galactic has more than 600 customers and reopened ticket sales in August, while Bezos said in July the company had as a backlog of nearly $100 million, although hasn’t disclosed how many people have signed up. After Inspiration4 splashed down, a SpaceX executive indicated there was enough demand for orbital flights to support five to six Crew Dragon missions a year.

Among the optimists is Dylan Taylor, CEO of Voyager Space Holdings and founder of the nonprofit organization Space for Humanity. “The number of people who have crossed the Kármán line is just a ridiculously small percentage of humanity,” he noted in a talk at the annual Mars Society conference on Saturday. “You’re far more likely to be a billionaire or a Nobel Prize winner than to have crossed the Kármán line.”

That’s changing with the emergence of suborbital and orbital space tourism at long last. “I do think we’re going to mint more new astronauts next year, in 2022, than any previous decade,” he predicted. “I see it accelerating tremendously, not only orbital launches with SpaceX, but also a lot of suborbital flights next year.”

| “I think it’s just a matter of time before we end up regulating more in depth commercial human spaceflight,” said the FAA’s Monteith. |

That acceleration won’t necessarily be smooth, though. Virgin Galactic has not flown SpaceShipTwo since that July flight where Richard Branson beat Jeff Bezos to space by nine days. In August, when Virgin announced it was reopening ticket sales—at significantly higher prices—it said both SpaceShipTwo and its WhiteKnightTwo carrier aircraft would begin an extended maintenance period this fall, after one more SpaceShipTwo flight for the Italian Air Force then scheduled for late September or early October. Commercial flights would not begin until late in the third quarter of next year.

Since then, the company has gone through an FAA investigation into why SpaceShipTwo deviated from its assigned airspace on that July flight, apparently because it was off its planned trajectory during its powered ascent. The FAA eventually cleared Virgin to resume flights, but by then the company was looking into technical issues, including a potential manufacturing defect. Late Thursday, the company announced it was starting its maintenance period now to address those issues, postponing the Italian Air Force flight to next year and delaying the start of commercial flights to the fourth quarter of 2022.

There are also regulatory issues. In the United States, the FAA has been restricted from developing safety regulations for spaceflight participants on licensed launches, a so-called “learning period” intended to give the industry time to build up experience upon which regulations could be based. Since its enactment in late 2004 for an original eight-year term, that learning period has been extended several times, most recently until October 1, 2023.

The surge in commercial human spaceflight may spell the end of the learning period. “I think it’s just a matter of time before we end up regulating more in depth commercial human spaceflight,” said Wayne Monteith, FAA associate administrator for commercial space transportation, during a panel discussion Thursday at the American Astronautical Society’s Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium in Huntsville, Alabama.

He said customers on those vehicles, as flights become more routine, “will want some assurance that you’re going to come back safely.” If there is an accident, particularly one involving a celebrity, “there are probably going to be calls for regulations, and regulations immediately.”

“It’s coming at some point. We want to get started sooner rather than later so we have the time to operate, time to work with industry to develop these appropriate, performance-based regulatory constructs,” he concluded. “I’m not sure what we’re waiting for, or what we’re still trying to learn.”

Despite those issues, it’s clear that commercial human spaceflight is becoming, if not routine, then more commonplace after an extended period filled with only promises and delays. But that also means, somewhat perversely, that the spotlight will be shifting away from the field. Blue Origin’s second suborbital spaceflight got the media attention it did because of the novelty of flying Shatner—Star Trek’s Captain Kirk—to space. Had a wealthy, but far less famous, customer taken his seat, it’s hard to imagine the major TV networks and other mainstream news outlets devoting as much attention to the flight. (An exception might have been in Australia: another passenger, Chris Boshuizen, became just the third Australian in space, after two who were NASA astronauts.)

Similarly, if Virgin Galactic had gone ahead with the SpaceShipTwo flight for the Italian Air Force this fall, it likely would have gotten only a fraction of the attention of Branson’s flight, at least outside of Italy. It’s likely to get more attention when it does take place next year, if only because it will mark the company’s return after what is shaping up to be a year-long hiatus from suborbital flights. But once the company does start regular commercial flights, individual flights will get little attention barring the presence of a celebrity or some other unique characteristic.

Space tourism is no longer on the critical path to low-cost launch, as some argued back in the early days of the X Prize a quarter-century ago. Smallsats and LEO constellations now provide the volume of payloads needed to close the business case for reusable low-cost launchers. But while commercial human spaceflight may fade from the limelight and from industry relevance, having more people, and a more diverse range of people, go to space is still vital, advocates argue.

“I do think that’s going to be transformational,” Taylor said of the rise of space tourism. “When we have people that people know who’ve been to space, and it becomes a more commonplace activity, I think we really have an opportunity to get people excited about the future.”

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.