Transfer of tensionby Jeff Foust

|

| “Generally speaking, the launch is of the order of 80% of the risk in a mission. I would say that… here it may be 20% or the risk, perhaps 30%,” said Zurbuchen. |

So, from the moment the Vulcain 2 engine in the core stage of the Ariane 5 ignited, followed seconds later by the two solid rocket boosters—the point of no return for the launch—they held their breaths. Their handiwork, and their futures, were in the hands of that rocket.

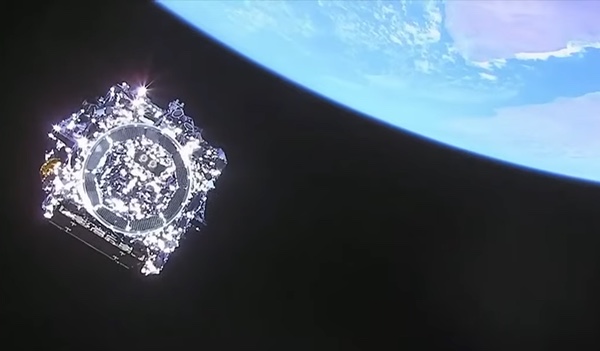

Twenty-seven minutes later, they could exhale. Right on schedule, JWST separated from the upper stage, bound for the Earth-Sun L-2 Lagrange point 1.5 million kilometers away. A camera on the upper stage captured the release of the telescope and, in a pleasant surprise, the deployment of the spacecraft’s solar array, which took place several minutes ahead of schedule. (NASA later said that the solar array was designed to deploy 33 minutes after liftoff or when it achieved a specific attitude, whichever came first; the accuracy of the launch meant it reached that deployment attitude early.)

Liftoff of the Ariane 5 carrying the James Webb Space Telescope. (credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls) |

“What we know now is that the injection was really perfect,” said Arianespace CEO Stéphane Israël at a briefing shortly after the launch. “It will help to have more lifespan for Webb.”

The accurate launch helps extend the lifespan of JWST by reducing the amount of propellant it needs to correct its orbit before arriving at L-2 29 days after launch. That conserves propellant for later stationkeeping maneuvers to maintain its halo orbit around L-2. In a December 29 statement, NASA said the propellant savings should support operations “for significantly more than a 10-year science lifetime,” but was not more specific.

But for JWST, the concern was never primarily about the launch. Instead, it’s what has to happen in the weeks after launch, as the telescope deploys major structures, notably its sunshield and mirrors. That will be followed by several months of commissioning of the telescope and its instruments as they cool to their operating temperatures a few dozen kelvins above absolute zero (see “For JWST, the launch is only the beginning of the drama”, The Space Review, December 20, 2021).

“Generally speaking, the launch is of the order of 80% of the risk in a mission. I would say that, by our analysis, by various ways of assessing that, here it may be 20% or the risk, perhaps 30%,” Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA associate administrator for science, said at that post-launch briefing. “We have retired quite some risk, but what is ahead remains is risk that we’re going to take down step by step.”

Those steps, at least initially, appeared to go according to plan. Key deployments like the spacecraft’s high-gain antenna, as well as the first two trajectory correction maneuvers, went as expected before controllers focused on the various steps in deploying the sunshield and stretching its five aluminum-coated Kapton layers into place, a process known as tensioning.

In a series of blog posts—NASA’s primary means of communicating updates on the mission in lieu of media briefings or other coverage—the agency stated that the deployment was going according to plan. The only hiccup came on New Year’s Eve, when the day passed without any news about the planned deployment of two booms that would extend the sunshield to its full size.

| “I’d be wiping my forehead if you could see me,” said Ochs. “Mid-boom deployment was huge. That was really a huge achievement for us.” |

Late in the day, NASA said the first of the two booms was now extended and the second was in progress. The delay, it said, was because of sensors that indicated a sunshield cover had not rolled up as expected. Other data, though, was consistent with the sunshield covers having been removed, giving engineers confidence that they could move ahead. The other boom completed its deployment less than two hours before East Coast calendars rolled over into 2022.

“Today is an example of why we continue to say that we don’t think our deployment schedule might change, but that we expect it to change,” said Keith Parrish, JWST observatory manager at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, in a statement Friday after the deployment of the first of the two mid-booms (emphasis in original.)

“I’d be wiping my forehead if you could see me,” Bill Ochs, JWST project manager at Goddard, told reporters in an audio-only teleconference Monday morning. “Mid-boom deployment was huge. That was really a huge achievement for us.”

But, as Parrish said, the deployment schedule has changed, as expected. The original schedule called for beginning the tensioning of the sunshield layers the day after the mid-boom deployments. But NASA announced Saturday that, because the mid-boom deployments went late into the evening Friday, they would take Saturday off. “We do not want to burn out our team along the way,” Ochs said.

The start of the tensioning process slipped to Sunday, then slipped again to Monday. In a Sunday blog post, NASA said engineers wanted to take time “optimizing Webb’s power systems while learning more about how the observatory behaves in space,” but provided few additional details.

In the Monday morning telecon—the first with reporters since that celebratory post-launch briefing—Ochs said controllers worked on two issues. One was a “preset max duty cycle” in the solar arrays that kept them from producing enough power to meet all spacecraft activities.

Engineers addressed that problem by tweaking the settings on each of five panels of the full array, said Amy Lo, vehicle engineering lead Northrop Grumman, so that “each panel of the array could be optimized to work at their best duty cycle possible.” That process was completed Sunday.

“We got the arrays to where they ought to be in order to provide the power that we need on Webb. We’re power-positive, the arrays look good,” she said.

The other issue, Ochs and Lo said, was with motors used to tension the sunshield. The temperatures were higher than expected, but still within margins. “We like to have a lot of operating margin for our motors—in fact, for anything that we do,” Lo said. “As we looked at the temperatures of the motors, they did not have as much margin as we would have preferred.”

The solution, she said, was to temporarily reorient the spacecraft so there was less sunlight shining on, and heating up, the motors. “They’re nice and cool. We’ve got a lot of margin now on our temperature.”

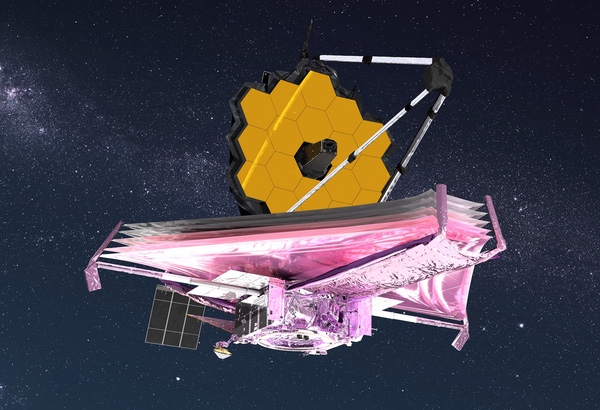

JWST will be fully deployed within a few weeks, although commissioning of the telescope and its instruments will take several more months. (credit: NASA GSFC/CIL/Adriana Manrique Gutierrez) |

Even as they spoke, controllers had started the tensioning process on the first of the five layers. Ochs said they will work layer by layer over two to three days to stretch the layers into the final shape, ensuring the proper separation between each layer so they can effectively cool the telescope and instruments.

| “The best thing for operations is boring, and that’s what we anticipate over the next three days, to be boring,” said Ochs. |

Completing the deployment of the sunshield won’t be the final step in getting JWST ready, but it will mean much of the most challenging work will be behind the team. “When we complete tensioning of all five layers,” Ochs said, “we will have retired somewhere between 70 to 75% of those 344 single-point failures that were discussed prior to the mission. That is huge.”

“I don’t expect any drama,” he added. “The best thing for operations is boring, and that’s what we anticipate over the next three days, to be boring. I think we’ll all breathe a sigh of relief once we get the final layer, layer 5, tensioning.”

In other words, as the tension in the sunshield increases, the tension among scientists and engineers will decrease. Assuming, of course, no drama in the process.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.