Starship status checkby Jeff Foust

|

| What they got instead was something like a concert from a rock star who has a new album coming out soon—but is not yet ready—and so falls back on some classics and maybe a track or two of new material. |

SpaceX moved later presentations onto home turf, including at its Hawthorne, California, headquarters in 2018 and at Boca Chica, Texas, in September 2019 (see “Starships are meant to fly”, The Space Review, September 30, 2019.) The company’s legion of fans, not to mention others in the space industry, had been impatiently awaiting the latest such update, particularly as the company edged closer to the first orbital launch attempt for Starship at Boca Chica, aka Starbase. That finally came last Thursday, an event Musk announced on Twitter just a week earlier (media got formal notifications of the event just a few days before it took place.)

The company, at least, created a stunning backdrop for the event: a fully stacked vehicle standing next to a tower. That tower helped assemble the vehicle: the night before, two arms dubbed “chopsticks” picked up the Starship upper stage, known as Ship 20, and lifted it in place atop the Super Heavy lower stage called Booster 4. The vehicle, 120 meters tall, towered over the assembled crowd of invited guests and media, many of whom could barely contain their enthusiasm about seeing the vehicle in person.

Yet the event itself was a little underwhelming, at least for those watching online. People tuned in expecting to get a major update on the impending launch of the vehicle looming over Musk and his audience at Starbase. What they got instead was something like a concert from a rock star who has a new album coming out soon—but is not yet ready—and so falls back on some classics and maybe a track or two of new material.

Much of the first part of his presentation recapped longstanding rationales for developing Starship: making life multiplanetary to preserve humanity as a hedge against terrestrial disaster and to “find out what this universe is all about.” That includes his belief that there is a window of opportunity to do so that opens now but may not be open forever, hence the urgency to start immediately. (“To be frank, civilization is feeling a little fragile these days,” he said.) To achieve that, Musk called for a vehicle capable of full and rapid reusability that can lift what he estimated to be a million tons of payload needed for a self-sustaining city on Mars.

Starship, at least in theory, is that vehicle. In charts he showed in his presentation, he said that a single Starship vehicle, launching three times per week, could place 15,500 tons of payload into orbit over the course of a year, or about 100 tons per launch. By comparison, the total mass to orbit by all launch vehicles to date is 15,517 tons.

But a Starship vehicle that could launch three times a day—something close to that rapid reusability desired by Musk—could place 109,500 tons in payload over a year. Ten such vehicles flying at the same cadence would place nearly 1.1 million tons into orbit after a year, that magic number he provided for establishing a self-sustaining Martian settlement.

| “We’re tracking to have the regulatory approval and the hardware readiness around the same time,” Musk said. “Basically, a couple months for both.” |

However, most of the audience either in person or online was already likely convinced of the importance of humanity becoming multiplanetary and believed that Starship was the vehicle that could make that happen: an almost literal preaching-to-the-choir moment by Musk. Can Starship really deliver, though?

Elon Musk provides an update on Starship progress at Boca Chica, Texas, aka Starbase, February 10. (credit: SpaceX webcast) |

Regulatory uncertainty

Musk had much less to say about where development of Starship stood. He talked about the design of Starship/Super Heavy and emphasized the superlatives in terms of size, mass, and thrust. “Super Heavy is the largest flying object of any kind—or will be,” he said of the booster. (Presumably Starship, when attached to Super Heavy, will be even larger.)

However, when exactly will Starship/Super Heavy fly? There are two factors governing that, one within SpaceX’s control and one largely outside of it, that Musk said would soon come together. “We’re tracking to have the regulatory approval and the hardware readiness around the same time,” he said. “Basically, a couple months for both.”

The regulatory approval comes from the FAA, which needs to issue a launch license for Starship orbital flights from Boca Chica. That license, in turn, depends on the completion of an environmental review, a draft version of which generated passionate public comments both for and against launches from the site (see “The battle for Boca Chica”, The Space Review, October 25, 2021).

Musk, speaking at a meeting of two National Academies committees in mid-November, said he expected an FAA license “around the end of this year,” a deadline the Department of Transportation offered in a “permitting dashboard” website tracking regulatory actions. But in late December the FAA said it moved the deadline to February 28, citing the need to review more than 18,000 public comments it received, along with “discussions and consultation efforts with consulting parties” such as environmental and wildlife agencies. As this article was being prepared for publication, the FAA announced another delay, to March 28, again because of public comments and “consultation and coordination with other agencies.”

At last week’s event, Musk seemed to expect that new delay in the regulatory process. “We don’t have a ton of insight into where things stand with the FAA,” he said. “We have gotten sort of a rough indication that there may be an approval in March, but that’s all we know.”

There is no guarantee that the environmental review will be done in March, given the past delays and similar slips for other projects, like the spaceport license awarded in December to Spaceport Camden in Georgia after years of delays. Moreover, the FAA could conclude that the environmental assessment (EA) was not sufficient, and instead call for a more thorough environmental impact statement (EIS).

| “It’s well-suited to be our advanced R&D location,” Musk said of Starbase. “It’s where we would try out new designs and new versions of the rocket.” |

That might rule out launches from Boca Chica at all for the foreseeable future, Musk acknowledged. “It would obviously set us back for quite some time because an EIS takes a lot longer than an EA, so we would have to shift our priorities to Cape Kennedy,” he said, a reference to the Kennedy Space Center at Cape Canaveral. SpaceX recently restarted work on a launch site for Starship vehicles at Launch Complex 39A, adjacent to the existing pad used by Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy vehicles. The company is also building a factory at KSC for Starship vehicles and is working with NASA on an environmental review for a new launch site, Launch Complex 49, on land at KSC set aside for a launch site in the center’s master plan.

Musk said that SpaceX could use an earlier environmental review for Starship launches from LC-39A to support launches from there, once a new launch tower was completed. “I guess our worst-case scenario is that we would be delayed for six to eight months to build up the Cape launch tower and launch from there,” he said. That assumes, though, that the older review is still valid given changes in the vehicle’s design, and that NASA is willing to allow an experimental vehicle to launch at a complex it relies on for getting astronauts to the International Space Station—not to mention all the other facilities at the center.

In the long run, though, Musk said that KSC, as well as floating platforms, would host most Starship launches. Starbase, billed by local residents as the “gateway to Mars,” would play at most only a supporting role. “It’s well-suited to be our advanced R&D location,” he said of Starbase. “It’s where we would try out new designs and new versions of the rocket. Cape Kennedy would be our main operational launch site.”

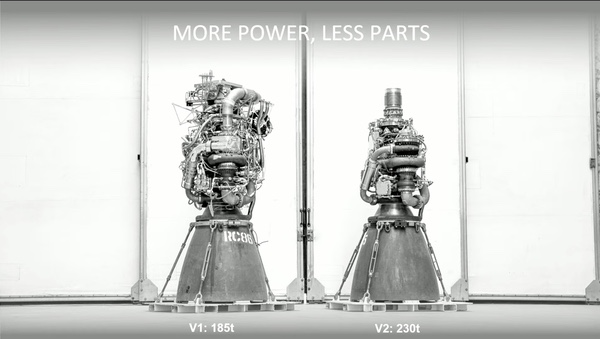

A comparison of the old and new versions of the Raptor engine that powers Starship/Super Heavy. (credit: SpaceX) |

Taming Raptors

The second factor is the technical readiness of Starship/Super Heavy itself. Despite the vehicle standing on the pad behind Musk, it’s unlikely that it would be ready to fly even if the FAA awarded Musk a license today.

At the National Academies meeting in November, Musk said he expected a first orbital launch attempt in January or February, shortly after getting an FAA license under the earlier timeline. Musk said then he expected a “bunch of tests” of the vehicle in December, but many of those tests were delayed. While there have been some tanking and static fire tests of Ship 20, there have not been static-fire tests of Booster 4 and its 29 Raptor engines.

Musk declined to discuss how much work needed to be done on the vehicle on the pad before it is ready for launch. “I think we're close to having the hardware ready to go,” was the most specific comment on that he provided.

The one area where he did go into new detail was on the Raptor engine design. The day after Thanksgiving, Musk sent an email to SpaceX staff warning of serious problems with the production of those engines that he said he found after “prior senior management” left—or had been fired—from SpaceX. Those problems, he wrote “have unfortunately turned out to be far more severe than was reported.”

| At Starbase last week, Musk did offer one prediction: “I feel, at this point, highly confident that we’ll get to orbit this year.” |

In that email, he warned SpaceX risked bankruptcy if the problem couldn’t be solved: the company needed Raptor engines for Starship vehicles needed to launch “V2” models of Starlink satellites that could not be launched on Falcon 9 rockets and which offered a much stronger business case than existing Starlink satellites. “What it comes down to is that we face genuine risk of bankruptcy if we cannot achieve a Starship flight rate of at least once every two weeks next year,” he wrote.

Musk publicly backed away from those comments in later tweets, calling bankruptcy a worst-case scenario if the company could not raise money. And, at last week’s event, he suggested the crisis had passed, with production of Raptor engines approaching one per day.

Those Raptors are a new version. “Raptor 2 is an almost complete redesign relative to Raptor 1,” he said. Whereas Raptor 1 could produce 185 tons of thrust, Raptor 2 can generate 230 tons, with plans to increase it to 250 tons. The new version is also “greatly simplified,” he said, which aids in manufacturing.

“Raptor 2 costs about half as much as Raptor 1 despite having much more thrust and just generally being a much easier engine to build, and a more robust engine,” he said, showing off a video of a test firing of that engine. “So Raptor 2 is pretty sick.”

Starship customers

Starlink will be an early customer of Starship, but SpaceX also is developing a version of the vehicle as a lunar lander for NASA’s Human Landing System program. “I don’t think there’s really a conflict there,” he said when asked if there was any conflict between launch vehicle work and the NASA award. “We’re going to be making a lot of ships, a lot of boosters.”

SpaceX also has a contract with Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa for his “dearMoon” circumlunar flight. “There are some future announcements that I think people will be pretty fired up about,” he said.

One of those announcements came Monday. Jared Isaacman, the billionaire who paid for and commanded the Inspiration4 Crew Dragon mission last September, announced a new initiative called the Polaris Program. That will start with a pair of Crew Dragon missions, the first scheduled for late this year, to test technologies needed for human space exploration. That includes the first spacewalk from the Crew Dragon spacecraft.

Polaris will culminate, Isaacman said, with the first crewed flight of a Starship, with him possibly on board (he will be on the upcoming Crew Dragon mission, called Polaris Dawn.) He didn’t give a schedule for that mission, though. “Long before we ever climb into Starship on the conclusion of the Polaris program, there’s going to be tons of Starlink missions and, I’m sure, other cargo and payload missions first,” he said in a call with reporters.

Not giving a schedule is probably a good idea given all the regulatory and technical uncertainties involved with Starship. At Starbase last week, Musk did offer one prediction: “I feel, at this point, highly confident that we’ll get to orbit this year.”

It’s worth remembering, though, what Musk said the last time he gave an update at Boca Chica, in September 2019. “And this is going to sound totally nuts, but I think we want to try to reach orbit in less than six months,” he said then. “Provided the rate of design improvement and manufacturing improvement continues to be exponential, I think that is accurate to within a few months.”

More than 28 months later, we’re still waiting on that first Starship orbital launch.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.