The moral equivalent of war: a new metaphor for space resource utilizationby Jack Reid

|

| What happens we fail to pursue space resource utilization, our “only way, really, to save this planet?” Why is space resource utilization the only alternative to destruction? Is it the only alternative? |

This is not the first time the space community has dealt with similar questions. As Matthew Tribbe wrote in No Requiem for the Space Age, the 1960s space race was discussed by both proponents and critics as having the potential to be a “moral equivalent of war” that could save us from nuclear holocaust. This phrase “moral equivalent of” has a long history in the field of ethics and might be useful when thinking about space resource utilization today, perhaps even more useful than the oft-employed frontier metaphor.

What is “the moral equivalent of war”?

The idea of a “moral equivalent of war” dates back to a 1906 essay by the pacifist philosopher William James. He argued that “So long as antimilitarists propose no substitute for war’s disciplinary function, no moral equivalent of war… as a rule they do fail.” War (or, more specifically, a military-like organization towards some concrete objective) provided discipline, support, and a productive, non-commercial outlet for ambitions at both the personal and societal levels. William James argued that a civil conscription service could fulfill this role, an idea that would later see implementation in New Deal programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps and the Works Progress Administration.

Isaac Asimov, Eric Sevareid, Ayn Rand, Norman Mailer, Werhner von Braun, are John Dos Passos are all figures who invoked the moral equivalent of war analogy. |

Others would come to see the space race as serving this purpose quite well. This included, more or less explicitly, critics such as journalist and writer Norman Mailer (Of a Fire on the Moon) and journalist Oriana Fallaci (If the Sun Dies) as well as supporters such as Wernher von Braun, Ayn Rand, sociologist Michael Harrington (“Left Should Reach for the Moon,” Washington D.C. Evening Star, January 7, 1969), and novelist John Dos Passos (On the Way to a Moon Landing). Another was CBS commentator Eric Sevareid, who pondered whether the space race could be “a moral substitute for war that could give the quarrelling human race some sense of common identity, of brotherhood.” Science fiction writer Isaac Asimov explicitly framed the moral equivalent in terms of mutually exclusive expenditures:

You know, the more money we put into space, the less money we have for arms and munitions. When people talk about how much it costs to go out into space, it seems to me that it’s much better to spend the money on that than on weapons. And I would like to see the various nations of the world no longer able to afford war because they’re putting too much money into space.

Such a belief has seen concrete policy manifestation. In the wake of the Soviet Union’s collapse, the US significantly expanded its cooperation with the Russian civilian space program, most notably in the form of the International Space Station. This involved significant financial and technical investments that were, in part, intended to keep former Soviet aerospace engineers engaged in peaceful pursuits within Russia rather than seeking to employ their skills for more violent purposes elsewhere. There were parallel similar cooperative activities and investments in Russia’s nuclear energy industry, such as the Megatons to Megawatts Program, for similar motivations.

| We are running out of places to run to for cheap resources and new markets, and all those externalized costs are coming home to roost. |

So, if this moral equivalent framing was so common during the original space race, why don’t we see it around more often today? Unlike the original concept, we are no longer talking about a moral equivalent of war, at least not directly. Bezos isn’t saying that mining asteroids are a substitute for war, though he might argue that it would indirectly reduce the frequency of armed conflicts. He is proposing space resource utilization as a substitute for some other, vaguer source of destruction.

Space resource utilization as a moral equivalent of what exactly?

The polar ice caps and glaciers are melting. Atmospheric carbon dioxide is on the rise. Wealth inequality is rapidly increasing. Our landfills are overflowing. We’re running out of metals for semiconductors and batteries. These are just some of the issues that the space resource utilization can help fix, according to proponents. Unfortunately, there is no single word for this mass of interconnected crises, but we can nonetheless try to describe it. Fundamentally, the issue, the disaster, that we are seeking an alternative to is that of a particular form of capitalism, one dependent on eternal growth and the externalizing of costs, situated in a finite capacity environment. What follows is a more detailed description of this coming disaster. It is perhaps an overly dour conception of human economic activity, but it is important to consider as it is the implicit alternative that space resource utilization is supposed to help us avoid.

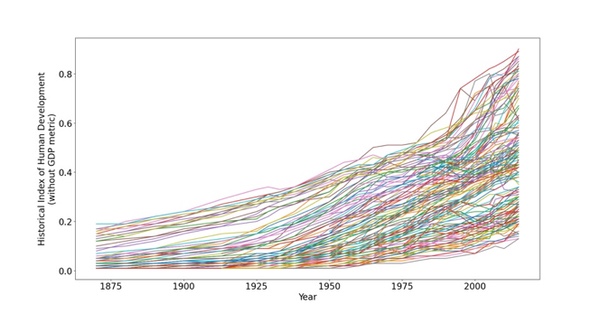

Leandro Prados de la Escosura’s Historical Index of Human Development for the nations of the world as published by Our World in Data |

For the past few hundred years, economic growth and technological advancement, often closely tied to capitalism, has raised average standard of living around the world. There are many obvious critiques of that statement. For instance, “average” does not accurately portray the entire distribution across the global population. “Standard of living” is a quantitative metric for a fundamentally qualitative experience, with all of the many flaws that comes along with such a conversion. Nonetheless, it is not unreasonable to suggest that life has improved. The global maternal mortality rate has fallen by approximately two orders of magnitude since the year 1800. The global infant mortality rate varied between 25% and 60% for most of human history, only to fall to less than 3% over the past couple of hundred years. The Historical Index of Human Development has skyrocketed over the past 150 years. The global literacy rate has climbed from less than 5% in the 1500s to almost 90%.

None of this is to deny the many, and recently increasing, inequalities that have come along with this economic growth. Arguably what benefits that have accrued to the population at large have occurred partially due to the fact that the global economy grew so obscenely fast over the past few centuries, only a large portion, rather than all, of the benefits could be captured by the financial elite (see Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century for an exhaustive treatment of this argument.) Nonetheless, because of these historical trends, large numbers of people around the world during the past couple of centuries could hope, and even have some expectation, that their children would be better off than their own generation was. It might take hard work, sacrifices, immigration to a foreign country, protests, or even revolutions, but the hope was there and it was not an unreasonable one. This hope has transformed into a now multi-generational expectation, an assumption that is firmly baked into contemporary culture.

A major underlying cause of all of this has been the continued, and sometimes problematic, acquisition and exploitation of resources, both human and natural, along with technologies that enable those resources to be acquired and exploited in new ways. New cheap energy sources: coal, steam, oil. New labor schemes: chattel slavery (see Edward Baptist’s The Half Has Never Been Told), child labor, factory sweatshops, outsourcing to one country after another, and, finally, automation. New trade systems: colonialism, banana republics, then free trade and globalization (see Ha-Joon Chang’s Kicking Away the Ladder.) New ways of externalizing costs: river dumping, sacrifice zones, denying the existence of such costs (e.g. leaded gasoline, cigarettes, climate change, all handily detailed in the book and film Merchants of Doubt.)

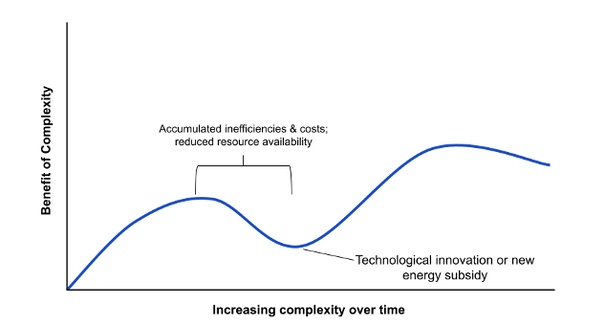

None of these are guaranteed to continue. In fact, there is some likelihood that they will not continue. Barring technological developments such as fusion energy, disasters (human-caused or otherwise) that dramatically reduce standard of living in major regions, or discovery of nearby intelligent alien life that we can trade with, we are running out of places to run to for cheap resources and new markets, and all those externalized costs are coming home to roost. Anthropologist Joseph Tainter in The Collapse of Complex Societies frames this in terms of the diminishing benefits of complexity in the face of rising costs.

The marginal product of increasing complexity. Adapted from Joseph Tainter’s The Collapse of Complex Societies |

So, what is next? One possibility is we dramatically revolutionize our economy and society to not depend on continual growth, if that is possible at all. I do not use the phrase “dramatically revolutionize” lightly here, however. Such alternative models involve fundamentally changing the dominant economic systems of the past few centuries. They would, in fact, be revolutions, peaceful or otherwise. And that should cause some concern. While there is plenty of optimism regarding such societal revolutions in science fiction, revolutions are a mixed bag. Cory Doctorow’s Walkaway and much of Kim Stanley Robinson’s work (specifically the Mars trilogy and New York 2140) show it working out all right, but we can’t guarantee such an outcome. Historical examples of revolutions devolving into dictatorship, totalitarianism, and authoritarianism are all too common; for another science fiction example, see Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Talents. When tearing down one power structure to erect another, there is a brief period between the two when anybody can grab the reins. And it is not clear that a sustainable, zero-growth economy with a high standard of living is particularly feasible.

Science fiction abounds with stories of societies using revolution, peaceful or otherwise, to escape from environmental and economic catastrophes. |

Another possibility is that wealthy individuals and corporations will seek to grow their personal holdings, to maintain the legacy of continual growth, and to ensure that their own children can have a better future. Unable to “grow the pie,” however, they will instead resort to claiming larger and larger portions of existing pie. In some ways this could be seen as a return to the economic theories of medieval Europe or the mercantilism of early modern colonialism, where trade between empires was largely prohibited and wealth was considered to be a zero-sum game between nations. In such a world, acquisition of wealth can only be accrued by taking it from others. This can be through direct competition with other corporations or members of the wealthiest classes, or through squeezing more out of the poor. Both tactics are seen in most cyberpunk dystopias like Neil Stephenson’s Snow Crash and the first portion of Walkaway. This would be what Tainter calls a collapse of a complex society taking place over the course of centuries.

| Similarly, the moral equivalent metaphor raises new questions in the space resource utilization context. Is it in fact a feasible alternative to a doomed Earth, a moral equivalent to competitive growth in a zero-sum environment? |

But what if we don’t have the end the game of continuous growth yet? What if there is some new technological breakthrough on the horizon, some new source of resources to be exploited? What if we can kick off another upwards exponential curve and stave off decline, or perhaps even prevent it altogether? Human settlement, industrialization, and utilization of space provides such a hope of salvation. According to proponents, space resource utilization can satisfy our desire, our need for continued growth and expansion, while avoiding either uncertain revolution or cutthroat competition in a zero-sum environment.

Some historical proponents of space settlement and resource utilization have used very similar framing. Physicist and author of The High Frontier, Gerard O’Neill stated during a speech at MIT:

I see before us two basic choices. There can be more wars, more restrictions on individual freedom, as we battle in what has to be a zero-sum game over the resources of our planet, or a new flowering opportunity with wealth for all humanity and the arts as we open a new frontier in space with more than a thousand times the land area and the resources of planet Earth.

More recently, some scholars have explicitly argued that, on the nation-state level, the restriction of resource exploitation to Earth will result in “more irresponsibility because problems of global governance become zero sum struggles. The more politically acceptable answer is that additional power resources available to spacefaring states, because of their annexations of extraterrestrial territories, would give them the means to better support global governance.”

Insights from a space-based moral equivalent framing

One of the primary benefits of ethical metaphors is to consider a situation from a new perspective, to help satisfy “the need to ask whether we are doing the right thing, for the right reasons, and in the best ways.” (See “‘Space ethics’ according to space ethicists”, The Space Review, February 1, 2021.) The classic frontier metaphor is one of expansion and glory, a “straight line, a vector of inevitability.” At the same time, however, it brings along with it questions of unjust and violent appropriation. Similarly, a moral equivalent metaphor forces us to ask questions about hard alternatives and motives.

In his book Pentagon of Power, sociologist Lewis Mumford considered the space race in terms of a moral equivalent of war. He thought it was possible for a space race to replace a specific war at a specific time (the US and the USSR) but that it would come at the cost of increased risk of destruction in the future. Meanwhile, Norman Mailer pointed out in Of a Fire on the Moon that if this moral equivalency was the true reason for pursuing the space race, it rather degrades the pursuit into something profoundly absurd, as “collective acts of hugely organized but ultimately pointless activity” that we only pursued because we “had not the wit, goodness, or charity to solve [our] real problems, and so would certainly destroy [ourselves] if [we] did not have a game of gargantuan dimensions for diversion.” Even Wernher von Braun, who argued that “at last man has an outlet for his aggressive nature,” also discussed the space race in much less uplifting terms: “Unless you give a small boy an outlet to vent his energy and his sense of contest he’ll come back home with black eyes. Then you can either chew him out and make a sissy of him or channel his energy into sport or skills. That’s the way it is with space.” Is that all we are, small, stereotypically masculine boys in need of distraction? Instead of indulging our competitive and ambitious instincts, should we instead try to moderate them?

Similarly, the moral equivalent metaphor raises new questions in the space resource utilization context. Is it in fact a feasible alternative to a doomed Earth, a moral equivalent to competitive growth in a zero-sum environment? If so, is it the only one? There are serious arguments to be made against feasibility, at least on the order of the next several decades to centuries. Many of these are well summarized in in James Schwartz’s The Value of Science in Space Exploration. If this is correct, the utilization of space resources may arrive either too late to avert a collapse or may only happen after one or more intermediate resource utilization advances occur, such as the invention of economical fusion energy. Concerns about such lack of feasibility, coupled with the concern that prioritizing space resource utilization and space settlement could reduce the priority of terrestrial sustainability (a potential second alternative to societal stagnation and collapse), has led to the argument that “There is no Planet B” and that we should focus on sustainability on Earth.

| It is perhaps overly dramatic (“utilize space resources or else”) and it is perhaps overly pessimistic about human nature and our ability to change. Nonetheless, I do believe it to be a more fruitful metaphor, one that helps us to interrogate why we wish to use space resources and thereby inform how we should go about using them. |

Another question that this framing raises is whether space resource utilization is a true alternative, either in the short term or long term. That is, by pursuing this alternative, are we merely running away from our real problem? This is akin to Mumford’s concern that the space race would merely heighten the risk of destruction in the future (which was arguably overly pessimistic considering the lack of apocalyptic war, nuclear or otherwise, since.) Perhaps space resource utilization wouldn’t, in fact, lead to any significant benefits to the population at large, due both to the high capital investments required to access these resources and due to the recent political/regulatory trends on Earth which are allowing increasing wealth and income inequality. Arguably, successful and exponential space resource utilization could result in humanity falling into the ultimate resource curse. In the long term, continued growth and expansion may hit another capacity wall further down the line. Maybe we use all of the accessible resources in the solar system before developing the means to extend our reach to other parts of the solar system or to other star systems. If that occurs, maybe the crash would be even worse than if we learned to live more sustainably now. On the other hand, perhaps space resource utilization will buy us enough time to develop the next game-changing energy source, transportation technology, manufacturing capability, or an economy that doesn’t rely on perpetual growth.

Obviously, no metaphor is perfect. The applicability of the frontier metaphor has been heavily criticized for decades. Similarly, the moral equivalent metaphor has its flaws. It is perhaps overly dramatic (“utilize space resources or else”) and it is perhaps overly pessimistic about human nature and our ability to change. Nonetheless, I do believe it to be a more fruitful metaphor, one that helps us to interrogate why we wish to use space resources and thereby inform how we should go about using them. I do not have answers to the various questions posed here, but as someone deeply invested in a space career (and lifelong fan of science fiction), I do hope that we can work together to answer them.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.