National Reconnaissance Program crisis photography concepts, part 1: A six-pack of Coronaby Joseph T. Page II

|

| “Once anxiety died away, the transient pressure to develop or deploy some system capable of performing near-real-time reconnaissance of designated areas rapidly diminished.” |

While NRP satellites were launched on September 29 (M9045) and October 9 (M9046A), the first was successfully recovered on October 13 before the crisis started, and the second had a ground resolution of 460 feet (140 meters), which was useless for anything but cartography.[1] Reconnaissance over the island of Cuba fell to Strategic Air Command’s U-2 spy plane and the US Navy’s fast-moving RF-8U Crusaders under the codename BLUE MOON.[2]

While the experts within the NRP pushed for near-real time electronic readout satellites (e.g. SAMOS), this technology had not proved successful during the time leading up to the crisis.

Robert Perry’s A History of Satellite Reconnaissance, Volume IV, recounts the undulating interest in responsive crisis reconnaissance:

The periodic revival of interest in crisis reconnaissance at intervals during the 1960s was clearly a byproduct of individual crises. Once anxiety died away, the transient pressure to develop or deploy some system capable of performing near-real-time reconnaissance of designated areas rapidly diminished. Characteristically, the systems that could be made quickly and cheaply available either for near-term use or for storage against some future need, tended to produce imagery with relatively little utility for crisis management. By the late 1965 there was general agreement that high resolution-pointing systems were essential to crisis reconnaissance, and they were expensive.[4]

The Egyptian-Israeli Six-Day War in June in 1967 and the Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 showed the both the scheduling gap of having a conflict between launches, and the inflexibility of photographic film systems.

The Six Day War (June 5–10, 1967) saw preemptive airstrikes by the Israeli Air Force against Egyptian and Syrian targets. After vicious fighting for five days, a cease-fire was agreed upon on June 10th. The NRP launches closest to the conflict were:

| Type | Mission No. | Launch Date |

|---|---|---|

| KH-7 | 4038 | 4 Jun 1967 |

| KH-4B | 1042 | 16 Jun 1967 |

| KH-8 | 4306 | 20 Jun 1967 |

The Warsaw Pact invasion of August 20–21, 1968, caught the Western world by surprise. Before the invasion, the Soviets moved troops with reinforcement from Hungary, Poland, East Germany, and Bulgaria under the guise of military exercises. Similar to the German “blitzkrieg,” these forces swiftly took control of Prague and other major cities, severing communication and transportation links. Two NRP missions were aloft in the weeks leading up to the Czech Invasion.

| Type | Mission No. | Launch Date |

|---|---|---|

| KH-8 | 4315 | 6 Aug 1968 |

| KH-4B | 1104 | 7 Aug 1968 |

Dr. James Outzen, director of the Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance (CSNR) later wrote:

[During] the 1968 invasion [of Czechoslovakia] by Soviet Forces, the US did have an imagery satellite in operation during the crisis. The satellite in fact captured images of the Soviet forces massing along the Czech border prior to the invasion. Unfortunately those images were not deorbited and developed for examination by intelligence analysts until after the invasion had occurred, providing no warning.[3]

While these issues in the late 1960s helped push the intelligence community toward the realization of requiring a near-real time satellite reconnaissance system, the reality of having such a system ready soonest was bleak. To bridge the gap between responsiveness and flexibility, a number of system concepts were proposed in the early 1970s, using both new and already available hardware. This article will cover the Six-Pack Corona vehicle.

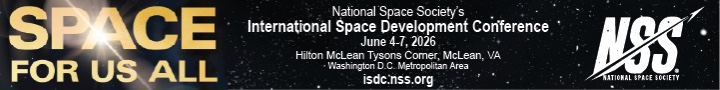

Six-Pack Corona Atlas-F Launch Vehicle. (credit: NRO) |

Like previous Corona space vehicles, the Six Pack vehicle used a standard J-3 camera (without DISIC) mounted inside an Agena upper stage for missions ranging from 20 to 30 days. The original design of the Six Pack was meant to keep the original system components unchanged, aside from the recovery section. The added weight of the additional film canisters and modification to inclination (limited to 60 to 80 degrees) ruled out the use of the SLV-2H Thorad. NASA’s SLV-2K, with the six strap-on solid rocket motors ,would provide enough lift capability but was deemed cost prohibitive. The lift solution would be found within then recently retired ICBM force: the Atlas F.[4]

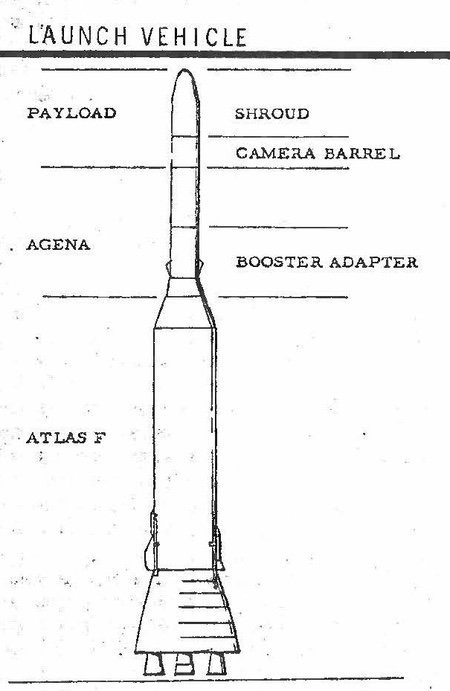

Inclination effects on Orbital Paths for Rev 1. Note the westward nodal shift from VAFB. (credit: NRO) |

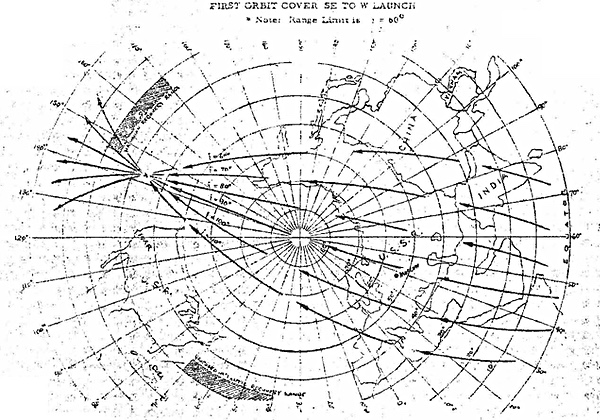

The recovery section concept carried six 24-inch (60-centimeter) diameter film canisters developed by General Electric, essentially scaled down versions of the Mark V reentry vehicle used by the Hexagon Mapping Camera System. Each take-up reel had a planned capacity of approximately 1300 feet (400 meters) of film, less than half used by Corona. [4]

| The main drawbacks to the Six-Pack Corona plan were inherent in the Corona hardware reuse. |

Launch facilities at Vandenberg’s SLC-3W would allow for a typical NRP recovery scenario, with the buckets arriving over the Pacific Ocean and grabbed from the air via JC-130 aircraft from Hawaii. Assuming the photos were developed and interpreted at Hawaii’s Overseas Processing and Interpretation Center – Asia (OPIC-A), reporting timelines were estimated to be as short as six hours after film retrieval.

The main drawbacks to the Six-Pack Corona plan were inherent in the Corona hardware reuse. The launch complex at Vandenberg offered very little benefit to coping with non-nominal crisis situations, as the launch pads were originally sited to support reconnaissance over high northern latitude locations (e.g. the Soviet Union).

24-inch J-3 Camera General Arrangement. (credit: NRO) |

A midnight launch from California would provide optimal sun illumination for targets in Europe, Africa, the Middle East, parts of China, and most of the Soviet Union and India. Immediate recoveries were limited to Rev 9, 10, or 11, nearly 15 hours from launch to first recovery opportunity. Any targets south or east of these areas would not see coverage until Revs 10 through 16. Daytime launches would push back first recovery opportunities even further, to Rev 25 through 27.

Film usage and management was also identified as a limiting factor since crisis mission requirements stated a daily readout or recovery over 30 days. Due to the increased number of film capsules, crisis managers could expect either daily recoveries over six days, or accumulate coverage to extend mission duration over a 30-day orbital life, popping off incomplete film buckets for re-entry as needed.

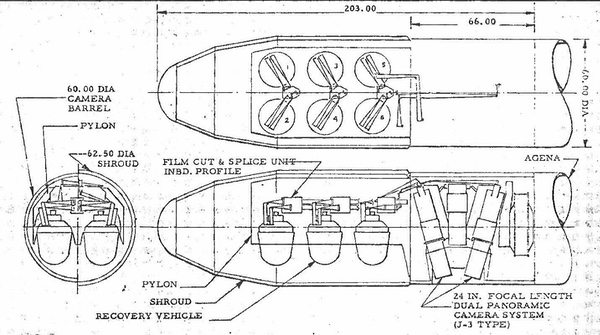

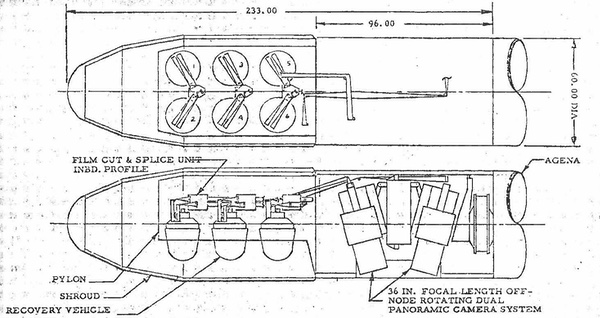

36-inch Off-node Dual Rotating Panoramic System Arrangement. (credit: NRO) |

Finally, the reuse of the J-3 camera provided an average resolution between 7 to 12 feet (2.1 to 3.7 meters), increasing to 5 feet (1.5 meters) at nadir and an altitude of 85 nautical miles (157 kilometers). The crisis management requirements identified 3-foot (0.9-meter) resolution for surveillance and 5 feet (1.5 meters) for search. A secondary camera option came in the form of 36-inch (90-centimeter) focal length, off-node rotating dual panoramic camera from ITEK. This camera fit within the confines of the diameter of the Agena, but was heavier than a standard J-3 and required a longer upper stage: 233 inches vs. 203 inches (5.9 vs. 5.2 meters). The tradeoff benefits included resolution of 2.75 feet (0.8 meters) at nadir (85 nautical miles altitude) and mission average of 3 to 4 feet (0.9 to 1.2 meters).[4]

While the ingenuity of the development team is obvious from the concept designs, the idea of Six-Pack Corona came near the end of the program (May 1972), too late to be considered useful within the rapidly changing world of the 1970s. Selecting the Six-Pack Corona would require both a restart of manufacturing for the camera and re-shuffling of the existing Agena upper stage assembly line as many were already destined for other NRP projects. [5]

The study of Six-Pack Corona took place around 1970–1971, about the same time as discussions about Film-Read Out Gambit (FROG) and ZAMAN/KENNEN for near-real time return. Even though the first electro-optical imaging (EOI) near-real time system would not launch until 1976, the KH-9 Hexagon would provide overwatch with an ingenious idea of a large satellite bus with six film return capsules and long mission durations.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.