Learning to let go of space missionsby Jeff Foust

|

| “As the power goes down, we’re not actually sure exactly how well the spacecraft will perform. It’s exceeded our expectations at just about every turn on Mars,” Banerdt said of InSight |

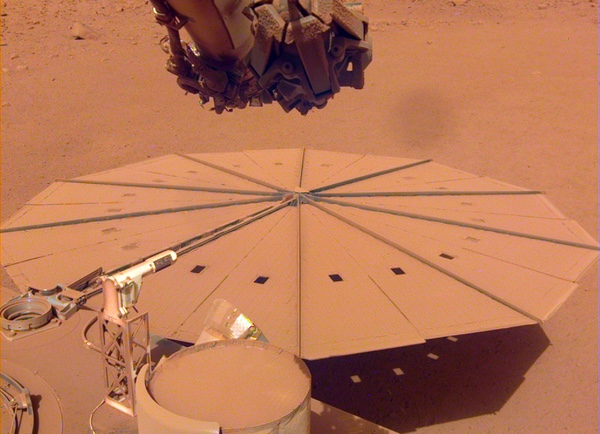

The announcement was not a surprise. Since last year, project leaders said they were aware of the dropping power levels caused by accumulating dust. They hoped for a “cleaning event,” like a dust devil passing over the lander that could remove the dust, similar to what happened to the Spirit and Opportunity rovers that kept them operating for years. However, no such cleaning events took place, and other measures—notably using the lander’s robotic arm to drop regolith near the panels, so that the wind would cause some pebbles to bounce off the panels and kick up dust—offered only a short-term fix.

NASA used a briefing to outline how the lander would spend its final sols on Mars. The arm would be placed in a final “retirement pose” so that a camera mounted on it could observe the seismometer, the lander’s main instrument. That seismometer will move into intermittent operations and then shut down completely as soon as July as power levels continue to drop.

It might hold out a little bit longer. “We’re in an operating regime we’ve never been in before,” Bruce Banerdt, InSight principal investigator at JPL, said at the briefing. “As the power goes down, we’re not actually sure exactly how well the spacecraft will perform. It’s exceeded our expectations at just about every turn on Mars. It may last longer than that.”

The problem led some to wonder why the mission didn’t have some means of cleaning the arrays: some envisioned a brush on the end of the robotic arm, wiping the arrays as one might dust furniture at home. Banerdt explained that was easier—and cheaper—said than done. “If we put more money into the solar arrays, we would have less to put into the science instruments, so we tried to find the right balance,” he said. (InSight, as part of NASA’s Discovery program, had to fit into a cost cap and had other issues, such as problems with the seismograph’s development that delayed the launch two years.)

Even with the solar array problems that are ending its life, InSight is a success, NASA argued: it operated well beyond its prime mission of one Martian year (a little under two Earth years) and met its science goals with its spectrometer despite problems with a heat flow probe that was unable to burrow into the surface. Weeks before the briefing, NASA announced InSight had measured its strongest quake to date, the equivalent of a magnitude 5.

But even successful, long-lived missions have to come to an end, someday. Around the same time that NASA held the briefing about InSight, it also reported an issue with the Voyager 1 spacecraft, launched nearly 45 years ago and now speeding out of the solar system. The spacecraft’s attitude control system was returning data that didn’t match the actual behavior of the spacecraft.

| “A mystery like this is sort of par for the course at this stage of the Voyager mission,” said Dodd. |

The spacecraft itself appears to be otherwise operating well, and the strength of the signal received by the Deep Space Network suggests the spacecraft is properly oriented. But the issue with what’s called the AACS could be a sign of more serious problems to come.

“A mystery like this is sort of par for the course at this stage of the Voyager mission,” Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project manager at JPL, said in a statement. “The spacecraft are both almost 45 years old, which is far beyond what the mission planners anticipated. We’re also in interstellar space—a high-radiation environment that no spacecraft have flown in before. So, there are some big challenges for the engineering team.”

The Ingenuity Mars helicopter, originally planned to make five flights, has flown 28 times, but not since late April. (credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech) |

The Ingenuity Mars helicopter is only a tiny fraction of the age of Voyager 1, but it has far exceeded its life. The experimental helicopter was originally designed to make up to five flights over a few weeks in April 2021, but then the project would end to allow the Perseverance Mars rover to continue on its mission.

Ingenuity, though, performed so well that it got an extension. “The scientists said, ‘This is really useful, let’s adopt it and make it an operation support element,’” recalled Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA associate administrator for science, during a meeting last week of the National Academies’ Space Studies Board. Ingenuity completed its 28th flight in late April, having served as a scout for Perseverance.

However, the onset of winter at Jezero Crater on Mars is affecting Ingenuity. The helicopter lost communications with Perseverance, and hence with Earth, for several days in early May because heaters to keep its electronics warm drained its batteries. The project has adapted by lowering the threshold temperature at which the heaters turn on, but has since lost an inclinometer, an instrument used to measure its orientation before the start of a flight, possibly because of exposure to cold temperatures.

The limited sunlight and thus power available during winter will keep Ingenuity largely on the ground until spring—if it survives. “In a handful of months we’ll start getting back into Martian spring where we get very energy positive again and back to business,” said Jaakko Karras, chief engineer for Ingenuity, after a talk at the International Space Development Conference in late May. Engineers have come up with a workaround to allow flights to continue without the inclinometer.

However, the mission is long into bonus time and dealing with conditions it was not designed for, since no one expected it to still be operating after more than a year. Zurbuchen, speaking at the Space Studies Board, wanted to set expectations accordingly.

“I want you to know, no matter that happens now, this is a huge success. And this too will end,” he said of Ingenuity. “We had every success that we wanted on this, and we will celebrate this. I don’t care what happens next. This is a success.”

| “Death is inevitable for all of us,” Zurbuchen said, “and it’s also inevitable for all the spacecraft.” |

He had similar views about the issues with Voyager 1 and InSight. “This mission is doing amazing science. It’s exploring the near-galactic environment,” he said of Voyager. The project team has solved similar problems in the past, he said, but one day may run into one it cannot. When that happens, “we should take out the champagne and not somehow pretend there is a problem.”

As for InSight, he noted he was in alignment with Banerdt on how to wrap up the mission. “We’re going to maximize the science, not the lifetime of the mission,” he said.

Banerdt said the same at last month’s briefing. “There really hasn’t been too much doom and gloom on the team. We’re still focused on operating the spacecraft,” he said. “We’re still figuring out how to get the most science out of it.”

Eventually every mission, no matter how long-lived, will eventually fail for one reason or another. “Death is inevitable for all of us,” Zurbuchen noted during the meeting, “and it’s also inevitable for all the spacecraft.”

But resurrection is possible, too. NASA’s extended mission or InSight is set to end this year, on the assumption that power levels drop below critical levels. However, if conditions improve in the spring as the landing site gets more sunlight, and if InSight finally gets a long-awaited cleaning event, the spacecraft could revive. NASA plans to check in next year for any signals from InSight.

“The Martian environment is very uncertain. We don’t know what’s going to happen,” said Kathya Zamora Garcia, InSight deputy project manager, at the briefing last month. “We’ll be listening.”

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.