FOBS, MOBS, and the reality of the Article IV nuclear weapons prohibitionby Michael Listner

|

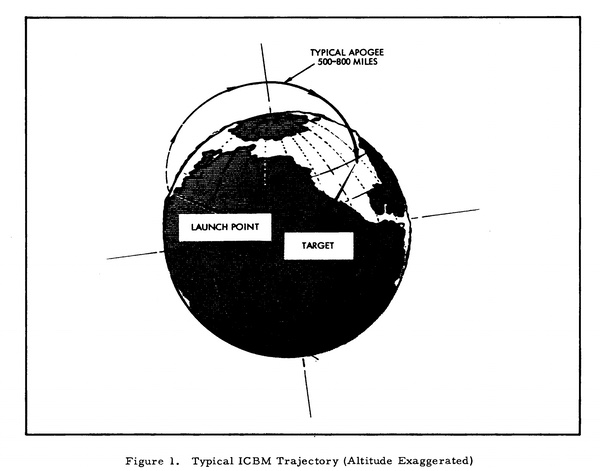

Figure 1. [3] |

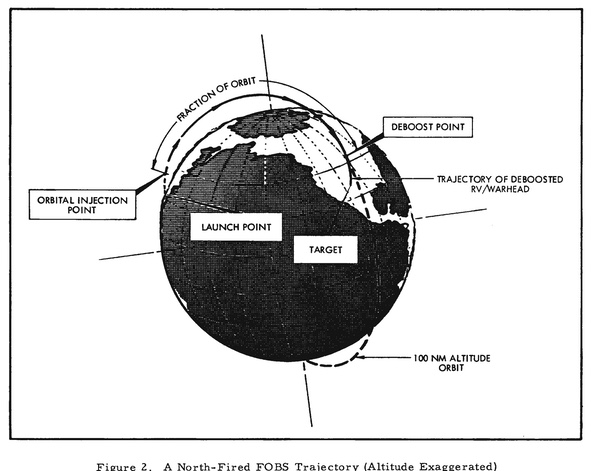

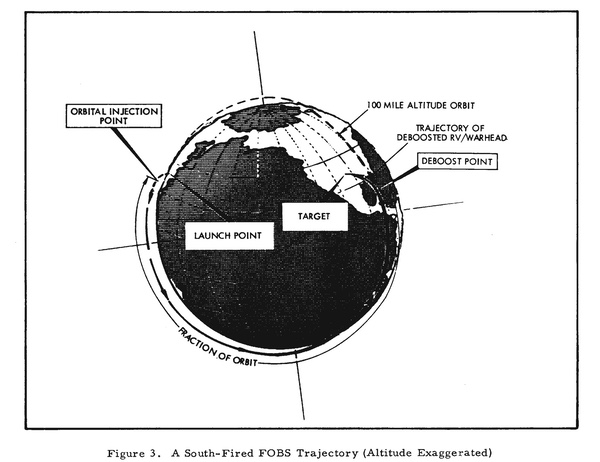

Comparatively, a FOBS trajectory launches a warhead and its delivery vehicle into an orbit of around 100 miles (160 kilometers) but breaks from that orbit before it completes a full revolution of the Earth.

Figure 2. [4] |

Figure 3. [5] |

Development of the Soviet FOBS began in 1962 with three proposed systems. Eventually, a system based on the R-36 (SS-9) ICBM was tested and deployed in 1968. This created a conundrum for the Soviet Union given the orbital nature of the system conflicted with the recently enacted Outer Space Treaty in 1967. The Soviets attempted to sidestep the conflict with the Outer Space Treaty by insisting the system would not make a complete orbit of the Earth.[6] It is this view that ultimately prevailed, as this essay will discuss.

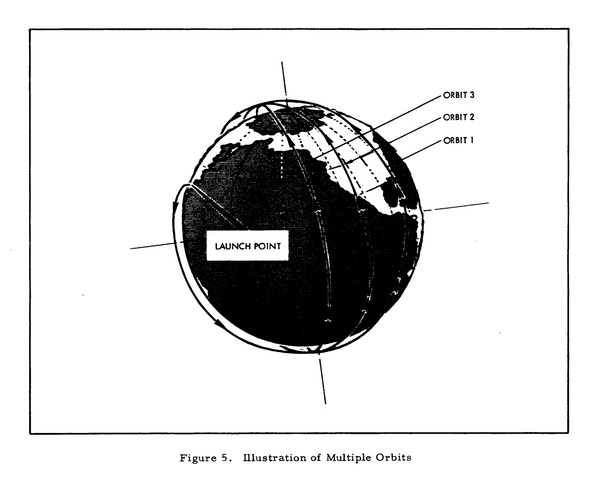

Another concept explored by the Soviet Union was the multiple orbit bombardment system (MOBS), also called the nuclear-armed bombardment system (NABS), where a vehicle carrying either a single or several warheads would make one or more complete orbits of the Earth before it delivered its payload. MOBS are differentiated from FOBS in as their weapons complete one or more orbits before descending on its target.

Figure 4. [7] |

Article IV, FOBS, MOBS, and McNamara’s analysis

The lawfulness of FOBS became relevant after Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara revealed in a November 3, 1967, press release the Soviet Union was developing a FOBS capability.[8] This was less than a year after the Outer Space Treaty went into force and represented one of the first policy tests of the nascent accord.

| Contemporary interpretation of the Outer Space Treaty assumes Article IV prohibits the presence of nuclear weapons in general in outer space and even their very existence. |

The policy challenge before the Johnson Administration was twofold: the first question was whether the Soviet FOBS test was a violation of Article IV. The second challenge was less pronounced and appears to be whether the administration should interpret the Outer Space Treaty in a manner that would allow the US to denounce the test and FOBS in general or apply Article IV as it was intended and thus preserve the original meaning of the Outer Space Treaty, even if it supported the Soviet test and a subsequent deployment of a FOBS.[9]

The first question is whether the FOBS test violated Article IV:

“States Parties to the Treaty undertake not to place in orbit around the Earth any objects carrying nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction, install such weapons on celestial bodies, or station such weapons in outer space in any other manner.”[10]

While at first blush the Soviet test appeared to be a direct a violation of Article IV, Secretary McNamara did not jump to this conclusion and consulted with Ambassador Goldberg concerning the original intent and obligations under the Outer Space Treaty.[11] From this discussion and other inputs Secretary McNamara concluded the testing of the Soviet FOBS did not violate the Outer Space Treaty. Secretary McNamara’s rationale and interpretation of Article IV, paragraph 1 is based in part on this conversation is indicated in a statement:

“The wording of this Article makes it absolutely clear that the Treaty is intended to prohibit the ‘carrying of nuclear weapons.’ The Treaty does not and was not intended to in any way prohibit the development or even the testing of systems capable of carrying nuclear weapons. I understand that there is no evidence of any kind or any reason to believe that nuclear weapons were associated with any of the Soviet tests of the FOBS.

Beyond this fundamental consideration that would exclude the violation of the Treaty* I believe it important to recognise that the intent of this Article was to outlaw military systems that would station nuclear weapons in orbit above the earth as a terror or blackmail threat during peacetime. To this end* the wording in the [deleted word] Article not to place in orbit around the earth’ was chosen with the intent of covering a system that would circle the earth many times. The wording was not intended to cover ICBMs or systems such as the FOBS which presumably would only be used with nuclear weapons in time of war.”[12]

With this evaluation of whether the FOBS test violated the Outer Space Treaty, Secretary McNamara further elaborated on this posture emphasizing the second policy challenge concerning interpretation of the Outer Space Treaty:

“I believe that the Outer Space Treaty is an important international obligation to which the major countries of the world have solemnly committed themselves. This Treaty can serve a most important role in preventing the proliferation of nuclear weapon* to the new environment of outer space. If we wish to develop the stature of this Treaty, we must be prepared to insist that its true obligations are honored. At the same time, we must be careful to avoid vague charges which cannot be substantiated that the Treaty has been violated. Such hasty actions can lead to counter charges that we are interested in employing the Treaty for a tactical, political advantage when it so serves our purpose. This can only serve to degrade the Treaty in the eyes of the world.”

Thus, Secretary McNamara highlights four critical points in his analysis:

- FOBS do not place nuclear weapons in orbit.

- The Outer Space Treaty does not prohibit the testing and development of weapons designed to carry nuclear weapons.

- There was no evidence the test carried a nuclear weapon.[13]

- It was politically expedient not to interpret the Outer Space Treaty outside of its true obligations.

There was pushback to this position in a memorandum dated November 4, 1967, from the executive secretary of the National Aeronautics and Space Council, Edward C. Welsh, to Walt Rostow, who was National Security Advisor to President Johnson that disagreed with Secretary McNamara’s interpretation noting:

“It is incorrect to conclude that a space object has not attained orbit until it has made a complete revolution of the earth. Once having been launched, a spacecraft is in orbit as soon as it attains an altitude and speed which would permit it to make a complete revolution of the earth. To bring down such an object before it has made a complete revolution does not amend in any regard a statement that it was an object in orbit around the earth.”[14]

Despite this pushback, Secretary McNamara’s position remained unchanged and is further bolstered by this argument:

“The wording [of the Outer Space Treaty] was not intended to cover ICBMs or systems such as the FOBS which, presumably would only be used with nuclear weapons in time of war.”[15]

This epitomizes the true intent of Article IV: FOBS are not prohibited by the Outer Space Treaty for the same reason as ICBMs: they are not intended to place satellites with nuclear weapons in orbit and will carry nuclear weapons into space only in the event of war.[16] Outside of war, both remain in their silos on the Earth outside of the influence of the Outer Space Treaty.[17] This is a significant policy consideration as it not only placed FOBS outside of the Outer Space Treaty, along with ICBMs, but also gave the Outer Space Treaty its first true test at interpretation and application.[18] More importantly, the US treatment of Article IV to resist recklessly interpreting the new accord for political benefit over a geopolitical adversary and thus weaken it before it had a chance to be strengthened by state practice was a significant policy decision.

| This epitomizes the true intent of Article IV: FOBS are not prohibited by the Outer Space Treaty for the same reason as ICBMs: they are not intended to place satellites with nuclear weapons in orbit and will carry nuclear weapons into space only in the event of war. |

McNamara’s analysis also appears to apply to MOBS even though his statement does not expressly mention it. It is clear MOBS and the question of nuclear weapons in outer space was also on the mind of others in the Johnson Administration. Spurgeon Kelly, referring to the November 4, 1967, memorandum from the executive secretary of the National Aeronautics and Space Council, raised the concern of MOBS in a memorandum to the National Security Advisor, noting:

“Ed Welsh makes an interesting technical point that a FOBS has in fact been placed in an orbit (as its name indicates). However, I believe that it is clear that it was not the meaning or intent of Article IV to cover this case. For Treaty purposes FOBS should be considered as an extension of the ICBM problem. At the same time, I think McNamara and Me interpreters have confused the issue and possibly created a problem for us by making such a sharp distinction between a FOBS and a MOBS since the Soviet system is clearly capable of multiple orbits. A MOBS would also clearly not be in violation of the Treaty unless it contained a nuclear weapon. However, in making a major point of the distinction between FOBS and MOBS, we are at least suggesting that a MOBS would be a Treaty violation. I do not believe we have really thought through how we would deal with a future Soviet MOBS firing in the absence of any evidence that it contains a nuclear warhead. I would therefore recommend soft pedalling this point until we know where we are going.”[19]

This memorandum appears to suggest Spurgeon Kelly had doubts about McNamara’s interpretation and analysis of FOBS and the Outer Space Treaty and how MOBS would be interpreted if the Soviets tested a device. However, while Kelly had his concerns about McNamara’s policy position, McNamara’s analysis extends to include MOBS with ICBMs and FOBS as falling outside the Outer Space Treaty, i.e. they are not placing satellites with nuclear weapons in orbit, and they would only carry nuclear weapons into outer space during a time of war.[20] An argument against this might be that a MOBS system completes one of more orbits before it descends on its target, which would make it a satellite. However, the key to MOBS being categorized with ICBMs and FOBS is that MOBS would be placed in orbit as an act of war not staged in orbit just in case of a war.

Interestingly, McNamara’s interpretation of Article IV finds support in the Treaty on the Prohibition of the Emplacement of Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction on the Sea-Bed and the Ocean Floor and in the Subsoil Thereof. From Article I(1):

“1. The States Parties to this Treaty undertake not to emplant or emplace on the seabed and the ocean floor and in the subsoil thereof beyond the outer limit of a seabed zone, as defined in article II, any nuclear weapons or any other types of weapons of mass destruction as well as structures, launching installations or any other facilities specifically designed for storing, testing or using such weapons.”[21]

The language of Article I(1) of the Seabeds Treaty appears to eschew the same principle of Article IV with regards to nuclear weapons. Like Article IV, Article I(1) treats the sea bed and nuclear weapons in a similar vein. Critically, the Seabeds Treaty is silent about other nuclear weapons platforms that traverse the seas, including submersibles and surface vessels, which implies these platforms fall outside of the Seabeds Treaty. This is similar to the silence in Article IV with regards to ICBMs, FOBS, and MOBS. The Seabeds Treaty is more specific than Article IV in its prohibitions, but the principle and motivation appears similar.

All things considered, the Soviet FOBS test presented an opportunity to put the Outer Space Treaty into practice and provided the Johnson Administration with at least four policy benefits:

- The Johnson Administration realized the opportunity to interpret the Outer Space Treaty so early after it entered into force was a watershed moment, which could either strengthen or weaken it. The administration’s decision to honor the true intent of the obligations instead of capriciously entertaining ambiguous interpretations for short-term political gain preserved the nascent accord and bolstered its legitimacy.

- The Soviet FOBS test presented an opportunity that spurred an interpretation of Article IV and the Outer Space Treaty early in its life that might otherwise not have arisen until later. The subsequent analysis and the stance taken by the Johnson Administration while the Outer Space Treaty was still fresh was not merely a legal exercise; it created a policy stance that overrode differing interpretations for how Article IV and the Outer Space Treaty would be interpreted by the US and by extension created state practice for Article IV that could arguably be considered a norm.[22]

- This interpretation of Article IV and the subsequent policy stance provided the Johnson Administration with legal support for anti-ballistic missile programs. Secretary McNamara announced the deployment of an ABM system called Sentinel on September 18, 1967, which was eight months after the signing of the Outer Space Treaty but before the Soviet FOBS test. Sentinel was promoted as a defense from a potential missile threat from the People’s Republic of China and employed long-range and short-range missiles that were armed with a nuclear warhead. The Spartan component of the system would reach an altitude of approximately 350 miles (560 kilometers) where it would detonate its nuclear warhead and disable incoming reentry vehicles with neutron flux and electromagnetic pulse. Since the interception altitude would be well within outer space, Secretary McNamara’s interpretation of Article IV would apply as would the rationale for the legality of ICBMs, FOBS, and MOBS: the Spartan would not place a satellite armed with a nuclear weapon in orbit and would only carry a nuclear warhead in time of war. Outside of conflict the warhead would remain in its launch canister on Earth outside the influence of the Outer Space Treaty. Thus, the Johnson Administration’s policy stance taking FOBS out of the Outer Space Treaty and giving the Soviets a diplomatic pass ensured nuclear-armed ABMs could be deployed without legal blowback.

- The Johnson Administration’s position legally vindicated the Soviet Union’s FOBS test and the 18 launchers that were deployed beginning in 1968, which could be considered a win for the Soviets. However, the policy position on Article IV also legally justified the deployment of a counter-measure for the Soviet FOBS initiated during the Kennedy Administration. Program 437 was the first ASAT deployed and used a Thor rocket armed with a nuclear warhead designed to intercept the FOBS warhead while it was still in orbit, detonate within proximity and disable the guidance system of the warhead with EMP.[23] Secretary McNamara’s interpretation of Article IV supported the deployment of the system because the Thor rocket would not place a satellite with a nuclear weapon in orbit and would only carry a nuclear weapon into outer space in the event of war. Otherwise, a nuclear-armed Thor remained on the pad and enjoyed the same status as ICBMs, FOBS, and MOBS. Therefore, just like the Sentinel ABM, validating the legality of FOBS and handing a win to the Soviets had the ancillary benefit of validating a counter measure.[24]

In summation, the prohibition in Article IV is a very narrow carve-out and not a blanket prohibition on nuclear weapons. This was intentional during the negotiation of the Outer Space Treaty, which prohibits an undesirable, expensive, and impractical means of basing nuclear weapons in satellites while excluding other nuclear weapon delivery systems not only from the Article IV prohibition but the Outer Space Treaty itself.[25]

| The treaty prohibits an undesirable, expensive, and impractical means of basing nuclear weapons in satellites while excluding other nuclear weapon delivery systems not only from the Article IV prohibition but the Outer Space Treaty itself. |

The Johnson Administration’s policy and subsequent state practice was not just a one-time application. The policy appears to be consistent and likely relied upon by successive administrations, including the Reagan Administration and its proposal for the Strategic Defense Initiative. The X-ray laser system under Project Excalibur in particular would have benefited from the policy as it certainly garnered Article IV scrutiny.[26] The system would have consisted of a small nuclear device launched aboard an ICBM or SLBM. When detonated in outer space it would have theoretically channeled a fraction of the energy released into high-intensity laser beams that would destroy enemy missiles either during their boost phase or mid-course. The device would be destroyed in the course of detonation and it is this operation of a nuclear weapon in outer space, and not the resulting laser beam, that would garner Article IV examination. Secretary McNamara’s interpretation of Article IV and the Johnson Administration’s policy position would have certainly vindicated the X-ray laser system. Under this policy the nuclear weapon that would power the X-ray laser would not be placed in orbit as a satellite nor would the nuclear warhead be present in outer space, unless there was a state of war. Otherwise the device would remain on its launcher, in a silo, or the launch tube of a SSBN giving it the same legal status of an ICBM, FOBS, MOBS, etc., which means it would fall outside the Outer Space Treaty.[27]

Resurgence of FOBS and concluding thoughts on Article IV

The advent of hypersonic technology and the resurgence of FOBS decades after the last system was deactivated has brought the same hair-trigger accusations about the legality of the weapon system.[28] However, declassified memorandums from the Johnson Administration outlining the policy position taken just months after the Outer Space Treaty went into force, the state practice that was created, which appears to have continued, and the possibility of a norm supporting this interpretation belies these indictments.

That FOBS fall outside the Outer Space Treaty closes a diplomatic and legal avenue to pushback against both the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation should either or both deploy such a capability, and it will compel policymakers such as the Defense Policy Board to consider other avenues and establish whether nuclear deterrence and missile defense remains viable.[29] The reappearance of FOBS will also compel decisions on whether a countermeasure is viable, including an anti-satellite weapon. However, decisions like this are political and hence uncertain, especially in the political backdrop of sustainability and space environmentalism. What is certain is nuclear weapons will probably not fit into the equation of a defense given the pragmatic effects they would have on satellite systems not to mention the potential for inadvertently triggering a nuclear exchange.[30] Regardless, the decision is not legal but one for policymakers.

| That FOBS fall outside the Outer Space Treaty closes a diplomatic and legal avenue to pushback against both China and Russia should either or both deploy such a capability. |

Even though it is improbable a nuclear weapon prohibited by Article IV will be deployed, that is not the end of the analysis. The Article IV prohibition is not limited just to nuclear weapons but any weapons of mass destruction.[31] Indeed, such a weapon system has been proposed in the “Rods From God” concept where a satellite armed with tungsten projectiles would orbit the Earth and deploy the projectiles on ground targets, using the kinetic energy of the projectile to destroy a target. Theoretically, the resulting release of kinetic energy would have a similar yield to a tactical nuclear device without the resultant radioactive fallout. This could classify the system and other similarly deployed kinetic bombardment systems as a weapon of mass destruction and trigger the prohibition in Article IV. However, an orbital kinetic bombardment system may not be practical for several reasons, including the Article IV prohibition, especially where it could be deployed on a FOBS or MOBS type system to not only avoid the logistical issues and expense or a deployed satellite but also avoid falling under the Outer Space Treaty.[32]

Whatever the future holds for the deployment of FOBS or MOBS by geopolitical adversaries, the prohibition in the Outer Space Treaty, while playing a large role at its inception, has been moderated by state practice such that it is only a consideration to be checked off on a legal checklist when evaluating nuclear weapon systems. Regardless, scholarly thought and ideology will continue to lionize the Article IV prohibition, but in the grander scheme of realpolitik the Article IV prohibition has merely made a squeak instead of a roar.

References

- See Gyurösi, Miroslav, “The Soviet Fractional Orbital Bombardment System Program,” January 2010 (Updated April 2012).

- An ICBM does travel a fraction of an orbit, but is designed to intersect the Earth’s surface and not go into orbit.

- Illustration taken from LBJ Library, NSF, Files of Spurgeon Kelly, “Memorandum: FOBS and the Outer Space Treaty,” November 21, 1967, Collection Title: Folder “FOBS & Radars,” Box Number 5.

- Illustration taken from LBJ Library, NSF, Files of Spurgeon Kelly, “Memorandum: FOBS and the Outer Space Treaty,” November 21, 1967, Collection Title: Folder “FOBS & Radars,” Box Number 5.

- Illustration taken from LBJ Library, NSF, Files of Spurgeon Kelly, “Memorandum: FOBS and the Outer Space Treaty,” November 21, 1967, Collection Title: Folder “FOBS & Radars,” Box Number 5.

- See Eisel, Braxton, “The FOBS of War,” Air Force Magazine, June 2005.

- Illustration taken from LBJ Library, NSF, Files of Spurgeon Kelly, “Memorandum: FOBS and the Outer Space Treaty,” November 21, 1967, Collection Title: Folder “FOBS & Radars,” Box Number 5.

- LBJ Library, NSF, Files of Spurgeon Kelly, News Release: Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense, November 3, 1967, Collection Title: Folder “FOBS & Radars,” Box Number 5.

- This was not the first time the Soviet Union tested a FOBS. Rather, it was the first test of a FOBS after the Outer Space Treaty went into force. Thus the issue was not just about the legality of FOBS but how the U.S. would apply Article IV and treat the Outer Space Treaty in general.

- Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, October 10, 1967, art. iv, para. 1, 18 UST 2410.

- Ambassador Goldberg was queried by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee about Article IV and the nuclear weapons provision and notes on page 22 of the transcript Article IV “…provides that any party shall not place any object into orbit, which means satellites, carrying nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction…” Treaty on Outer Space, Hearings Before Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, 90th Congress, 1st Session, March 7, 13 and April 12, 1967. Notably, Ambassador Goldberg used the term “satellites” when referring to weapons prohibited.

- LBJ Library, NSF, Files of Spurgeon Kelly, “Statement on FOBS, SMK draft,” November 8, 1967, Collection Title: Folder “FOBS & Radars,” Box Number 5.

- Under this analysis not all of the elements need to be met to bounce FOBS out of Article IV.

- LBJ Library, NSF, Files of Spurgeon Kelly, “Memorandum for the Honorable Walt Rostow: FOBS,” November 4, 1967, Collection Title: Folder “FOBS & Radars,” Box Number 5.

- LBJ Library, NSF, Files of Spurgeon Kelly, “Statement on FOBS, SMK draft,” November 8, 1967, Collection Title: Folder “FOBS & Radars,” Box Number 5.

- See Footnote 11.

- Placing these weapons outside of the Outer Space Treaty means the “peaceful purpose” provision of Article IV would not be an influence as well. See Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, October 10, 1967, art. iv, para. 2, 18 UST 2410.

- Another concern the Johnson Administration might have been considering is the issue of the delimitation of where the atmosphere ends and outer space begins. Suggesting that the FOBS indeed violated Article IV might bring to issue whether a delimitation was needed. That is to say, by asserting a FOBS was in orbit for purposes of Article IV might have run contrary to U.S. policy and put the U.S. in the position to admit a spatial demarcation needed to be recognized by international law.

- LBJ Library, NSF, Files of Spurgeon Kelly, “Memorandum for Mr. Rostow: FOBS and the Outer Space Treaty,” November 8, 1967, Collection Title: Folder “FOBS & Radars,” Box Number 5.

- LBJ Library, NSF, Files of Spurgeon Kelly, “Statement on FOBS, SMK draft,” November 8, 1967, Collection Title: Folder “FOBS & Radars,” Box Number 5.

- Treaty on the Prohibition of the Emplacement of Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction on the Sea-Bed and the Ocean Floor and in the Subsoil Thereof, art, i(1), February 11, 1971, 955 U.N.T.S. 115, entered into force May 18, 1972.

- “Treaties may constitute evidence of customary international law, but “will only constitute sufficient proof of a norm of customary international law if an overwhelming majority of States have ratified the treaty, and those States uniformly and consistently act in accordance with its principles.” “Of course, States need not be universally successful in implementing the principle in order for a rule of international law to arise ....but the principle must be more than merely professed or aspirational.” United States v. Bellaizac-Hurtado, 700 F.3d 1245, 1255 (11th Cir. 2012), Bellaizac-Hurtado, 700 F.3d at 1255 citing Flores v. Southern Peru Copper Corp., 414 F.3d 233, 248 (2d Cir. 2003). “A customary international law norm will not form if specially affected States have not consented to its development through state practice consistent with the proposed norm.” Bellaizac-Hurtado. at 1255 citing North Sea Continental Shelf Cases (Fed. Republic of Ger. v. Den.; Fed. Republic of Ger. v. Neth.), 1969 I.C.J. 3, 43 (Feb. 20).

- See generally, Clayton K.S. Chun, “Shooting Down a Star: Program 437 – The U.S. Nuclear ASAT System and Present-Day Copycat Killers,” USAF and Air University Press, September 9, 2012.

- One of the concerns for Program 437 that led to its deactivation was the specter about the use of nuclear weapons in outer space. However, it does not appear the concern was about the legality but rather the political consequences of the system mistakenly being deployed and triggering a nuclear exchange between the superpowers. See e.g. Clayton K.S. Chun, “Shooting Down a Star: Program 437 – The U.S. Nuclear ASAT System and Present-Day Copycat Killers,” USAF and Air University Press, September 9, 2012, p. 28.

- Secretary of State Dean Rusk noted during the Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearings on the Outer Space Treaty these types of systems are more expensive than others and would be difficult to maintain readiness. He also noted these types of systems pose the concern for the deploying state they could accidently return to earth and even perhaps in their own territory. Treaty on Outer Space, Hearings Before Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, 90th Congress, 1st Session, March 7, 13 and April 12, 1967, p. 26.

- The Director of Space Law and International Law, Headquarters, U.S. Air Force Space Command appears to have argued in 1985 the X-ray laser component of SDI could violate Article IV. The argument was two-fold: 1) is the X-ray laser a “nuclear weapon” and 2) will it be placed in orbit in outer space? See Smith, Milton, “Legal Implications of a Ballistic Missile Defense, 15 Cal. W. Int'l L.J. 52, 70-71. (1985). See also Maj. John E. Parkenson, Jr., International Legal Implications of the Strategic Defense Initiative, 116 MIL. L. REV. 67, 79-80 (Spring 1987), pp. 87-89. However, given the memorandums and the insight contained were only declassified over 20 years after SDI, it appears the Reagan Administration may have used the Johnson Administration’s analysis and interpretation of Article IV, which was classified at the time, to place X-ray lasers outside of the Outer Space Treaty.

- This does not mean other treaties, including the Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963, would not have affected the deployment of the system. See generally, Smith, Milton, “Legal Implications of a Ballistic Missile Defense, 15 Cal. W. Int'l L.J. 52. (1985). See also Maj. John E. Parkenson, Jr., International Legal Implications of the Strategic Defense Initiative, 116 MIL. L. REV. 67 (Spring 1987), for a discussion of the X-ray laser and the legal issue surrounding SDI).

- The 18 FOBS deployed by the Soviets were part of the SALT II treaty negotiations in Article VII, Second Common Understanding. Even though SALT II was not ratified, the Soviets began dismantling the FOBS installations in 1982 and completed the work in 1983. Eisel, Braxton, “The FOBS of War,” Air Force Magazine, June 2005. This was likely done not out of a sense of legal obligation to the unratified SALT II, but rather because the system was obsolete and redundant. It is likely the Soviets kept the FOBS active for as long as they did to use them as a bargaining chip to preserve other more valuable strategic assets during negotiations as opposed to good faith bargaining. Critically, including FOBS in SALT II was an arms control decision and not does not appear to be a statement FOBS violated Article IV of the Outer Space Treaty.

- Policy considerations for addressing FOBS is beyond the scope of this essay; however, it is notable after the PRC FOBS test was announced two authors presented a briefing that addressed the test and recommended more dialogue and strengthening of international agreements to prevent misconceptions about space technologies. In the intervening time it appears the “alarm” over the PRC FOBS test is not misplaced as implied by statements from DoD officials and the classified meeting of the Defense Policy Board. Moreover, the only standing treaty that tacitly addresses outer space security is the Outer Space Treaty. It appears the authors may be implying the duty to consult in Article IX should be invoked; however, this is a non-starter given the duty to consult nor the right to consultation has not been invoked and is likely an aspirational provision, especially for national security space activities. Moreover, since FOBS fall outside the Outer Space Treaty, Article IX would not apply anyways, and it would not be beneficial to either try and cram FOBS into the Outer Space Treaty and create a state practice that would be detrimental in the future, nor would it be wise to invoke the right to consultation in Article IX and create a state practice that would be used as lawfare weapon by both the PRC, the Russian Federation and its client states.

- See Endnote 24.

- The definition of weapon of mass destruction is a subjective legal question that is reliant on a political decision. Therefore, this essay will not delve into what “weapon of mass destruction” means.

- The PRC appears to be developing just such a system. See generally, “China unveils 3 ‘wide-area aircraft’ suspected to be Rods of God weapons,” China Arms, November 24, 2020.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.