Trials and tribulations of planetary smallsatsby Jeff Foust

|

| Some are the technical issues inherent in spacecraft design, when technologies don’t work as planned, or cost more or take longer than expected. The three missions also have the shared problem of finding rides to space. |

Planetary science is a different story, though. In those other disciplines, spacecraft can operate in Earth orbit or in the general vicinity of the planet: Earth science smallsats look down, while astrophysics smallsats look up. Planetary missions, though, are expected to study their objects in situ: flying by, orbiting, or landing on solar system destinations. That creates new challenges for both developing and launching such missions.

That is perhaps best illustrated by an ongoing NASA program called Small, Innovative Missions for PLanetary Exploration, or SIMPLEx. In 2019, NASA selected three mission concepts for further study that would use smallsats to study the Moon, Mars, and asteroids, with a cost cap of $55 million each. The agency originally expected to proceed with only one mission but was impressed enough with all three that it elected to proceed with them, finding funding from other parts of the science budget to support them.

All three, though, have run into problems. Some are the technical issues inherent in spacecraft design, when technologies don’t work as planned, or cost more or take longer than expected. The three missions also have the shared problem of finding rides to space, demonstrating some of the unique challenges planetary smallsat missions face (see “The perils of planetary rideshares”, The Space Review, July 5, 2022).

Lunar Trailblazer

One of the three SIMPLEx missions is Lunar Trailblazer. The smallsat is designed to orbit the Moon, studying the distribution of water ice the presence of water using a spectrometer and thermal mapper.

NASA arranged for the launch of Lunar Trailblazer as a secondary payload on another NASA mission, called Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP). The problem for Lunar Trailblazer was that IMAP’s launch was slipping: while Lunar Trailblazer was, at one point, working to be ready for launch by late 2022, but IMAP’s launch had been delayed to early 2025.

Scientists lobbied NASA to find another ride for Lunar Trailblazer rather than have a spacecraft—particularly one that could support other lunar missions, as well as the agency’s Artemis human lunar campaign—sit on the ground waiting for IMAP. One option would be for Lunar Trailblazer to hitch a ride with one of the commercial lunar lander missions through NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program.

NASA was initially skeptical that could work. “We’re buying a service from them, and the service we’ve contracted with them is for the instrument payloads,” Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s planetary science division, said at a committee meeting in the spring of 2021.

However, NASA pressed ahead and, by last June, found a new ride for Lunar Trailblazer. The spacecraft would fly as a secondary payload on IM-2, the second lunar lander mission by Intuitive Machines and one of NASA’s CLPS missions. Doing so, NASA said, resulted in additional cost for the mission, which NASA’s Lunar Discovery and Exploration Program would cover. IM-2 was, at the time, scheduled to launch in mid-2023; it’s now planned for around October, still more than a year ahead of IMAP.

| The mission replanned the work remaining on the spacecraft and “will also implement changes to reduce programmatic risks and seek out more operational efficiencies going forward,” NASA said. |

All seemed to be going well for Lunar Trailblazer until last August, when NASA announced the mission had overrun its cost estimate, prompting what is known in the agency as a “continuation/termination” review: a decision on whether to proceed with the mission or cancel it.

“There’s been some increases in the cost with the spacecraft development, and so we are working now towards a cost review that’s going to take place later this fall,” Glaze said at a meeting of the Lunar Exploration Advisory Group last August.

The problem was with the spacecraft’s prime contractor, Lockheed Martin. “As we brought this mission from paper to life, the engineering and design efforts exceeded our original estimate,” the company said in a statement, adding it was looking for “operational efficiencies” to minimize its growing cost.

By November, the verdict was in: Lunar Trailblazer would continue. The mission replanned the work remaining on the spacecraft and “will also implement changes to reduce programmatic risks and seek out more operational efficiencies going forward,” NASA said, without elaborating on the specific issues that caused the overruns.

NASA said Lunar Trailblazer had a new cost estimate of $72 million, 30% over its original cap. That included not just the overruns from Lockheed Martin, NASA said, but also the change in launches and other factors.

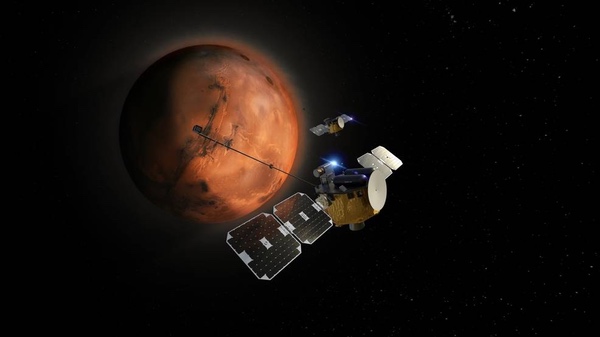

The revamped ESCAPADE spacecraft will launch to Mars on Blue Origin’s New Glenn in late 2024. (credit: Rocket Lab USA/UC Berkeley) |

ESCAPADE

The problems with Lunar Trailblazer, though, were modest compared to its SIMPLEx siblings. A second mission selected by NASA was Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers, or ESCAPADE (sometimes EscaPADE). It would send two smallsats to Mars to study how the solar wind interacted with the planet’s thin atmosphere.

ESCAPADE was originally designed to fly as a secondary payload on the launch of Psyche, a Discovery mission to the metallic main belt asteroid of the same name. ESCAPADE would be dropped off as the Psyche spacecraft made a flyby of Mars on its way to the asteroid Psyche.

Those plans were based on a Falcon 9 launch of Psyche. However, NASA instead selected the larger Falcon Heavy to launch the mission. That required a redesign of the mission that initially looked feasible, but at a review in August 2020, the agency concluded it was no longer able to accommodate ESCAPADE on the Psyche launch. The mission was put on hold.

ESCAPADE found new life in June 2021 when the University of California Berkeley’s Space Sciences Laboratory, which was developing ESCAPADE, announced a new deal with Rocket Lab to develop the two spacecraft. The company would provide a version of its Photon bus with greater propulsion capabilities.

However, the announcement said nothing about its launch other than the agency was planning a 2024 launch on a “NASA-provided commercial launch vehicle.” It was not until February 9 that the agency announced it had procured a launch for the mission through its Venture-Class Acquisition of Dedicated and Rideshare (VADR) program, awarding a task order to Blue Origin to launch ESCAPADE on the company’s New Glenn rocket in late 2024.

| The contract was noteworthy because it was the first NASA mission Blue Origin’s New Glenn had won a contract to launch. |

“ESCAPADE follows a long tradition of NASA Mars science and exploration missions, and we’re thrilled NASA’s Launch Services Program has selected New Glenn to launch the instruments that will study Mars’s magnetosphere,” said Jarrett Jones, senior vice president for New Glenn at Blue Origin, in a company statement.

The contract was noteworthy because it was the first NASA mission Blue Origin’s New Glenn had won a contract to launch. That vehicle, years behind schedule, has yet to make its first launch and the company has not provided a recent update on when it will fly.

It was also noteworthy in that the NASA announcement of the award didn’t disclose its value. Last November, when NASA also used VADR to award Rocket Lab a task order to launch its four remaining TROPICS cubesats (after the first two were lost on a failed Astra Rocket 3.3 launch), the company claimed the value of the award was proprietary. “Pricing provided in response to launch service task orders under VADR are competed in a closed environment and as such are considered proprietary to the indefinite-delivery/indefinite-quantity contract,” an agency spokesperson said at the time.

NASA gave a similar explanation for not disclosing the value of the award for launching ESCAPADE. As it turned out, though, the value was publicly available in a government procurement database: $20 million. That suggests that either ESCAPADE will fly as a rideshare with other payloads, or Blue Origin is providing a heavily discounted price for what could be one of New Glenn’s first launches.

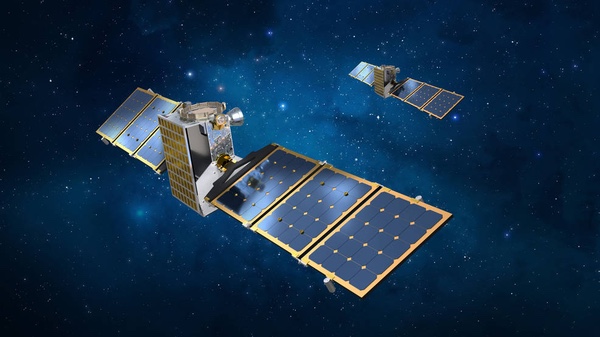

Janus is now looking into alternative missions after a delay in the launch of its original rideshare host, Psyche, kept it from carrying out its original plans. (credit: Lockheed Martin) |

Janus

Janus, a pair of smallsats to fly by binary asteroids, was also manifested to launch as a secondary payload on Psyche. It stayed on the mission even after ESCAPADE was kicked off, and appeared to be on track to fly last year.

Now, though, Janus is the SIMPLEx mission in greatest peril. Problems with the Psyche mission delayed its launch from August to October 2022, then to October 2023. That forced the Janus mission to see what asteroids it could reach with that new launch date.

The problem, said Dan Scheeres, principal investigator for Janus at the University of Colorado, at an advisory committee meeting last month, is that the new launch date for Psyche includes a new trajectory that takes the spacecraft further into the asteroid belt, depriving the Janus smallsats of solar power.

“This new launch would send our spacecraft beyond their operating envelopes in a matter of months,” he said. “Within five months, we wouldn’t have enough power to do anything. So, basically, we’d be a brick in less than five months.”

Janus is now without a ride, after NASA agreed to formally remove Janus from the Psyche launch last November. “Suddenly, we don’t have a launch,” he said. “Suddenly, everything we were designed to do is not nominally achievable.”

A further complication for Janus is a problem with the spacecraft’s propulsion system. NASA officials like Glaze had hinted at problems in recent presentations without going into detail, suggesting that those problems could have prevented the smallsats from carrying out its original mission of binary asteroid flybys.

| “Within five months, we wouldn’t have enough power to do anything. So, basically, we’d be a brick in less than five months,” Scheeres said. |

Scheeres said that Janus changed its propulsion system between proposal submission and selection when it became clear to the team that the original vendor could not deliver. The project switched companies and passed a series of reviews, but the electric thruster was not able to complete a 2,000-hour ground test intended to assuage concerns about it. He said the test was stopped after about 1,350 hours because of “specific issues with the test setup and operation” and not necessarily a problem with the thruster itself.

“The risk posture for SIMPLEx missions like Janus is that they are high-risk and low-cost, with the intention of proving out new technologies. For smallsats in particular, there are few flight-proven propulsion systems currently available,” Lockheed Martin, which is the prime contractor for Janus, said. “In Janus’ case, the full performance envelope of Janus’ novel electric propulsion system could not be verified in ground testing.”

But with the uncertainty about the propulsion system, though, there is no guarantee that Janus will ever fly. Scheeres said NASA directed the mission to use its remaining resources to look at alternative missions for Janus. One possibility is to use one or both Janus smallsats to fly by the asteroid Apophis before that asteroid makes a close flyby of Earth in April 2029. He said the spacecraft could launch as late as early 2028 and arrive at the asteroid before the flyby, and do so within the reduced tested lifetime of the propulsion system.

The alternative mission, though, might need more funding. “They could come back to us with a new proposed plan,” Glaze said of Janus at a town hall meeting in December, “but at this point it would be a new mission.”

Scheeres is not giving up. “We’re not dead yet.”

Lessons learned

One clear message from the experiences is that the budget for SIMPLEx missions is too small. Besides Lunar Trailblazer’s cost overruns, ESCAPADE has also seen its costs grow: a conference presentation last year estimated a total cost of $78.5 million, including launch and project reserves. Janus will likely need more money, too, if NASA signs off on an alternative mission to Apophis or elsewhere.

| “A higher cost cap would enhance the potential of the program to achieve decadal-level science and drive innovation across more destinations,” the decadal survey recommended. |

That was a conclusion last year’s planetary science decadal survey reached. “However, the challenging budgets, schedules, and coordination of rideshares or small launch procurement for SIMPLEx missions requires strong NASA stakeholder engagement with the mission team,” the decadal stated, suggesting that the missions selected to date for SIMPLEx reflect “low-hanging fruit” that are already pushing the limits of the cost cap.

It recommended increasing the SIMPLEx cost cap by about 50%, to roughly $80 million. “A higher cost cap would enhance the potential of the program to achieve decadal-level science and drive innovation across more destinations.”

Launch is also an issue, given the rideshare challenges all three missions have faced. Rideshare opportunities are less frequent for planetary missions given launch windows that are often narrow and increased delta-v requirements. The VADR contract might provide options for affordable dedicated launches, like ESCAPADE’s launch on New Glenn.

The fundamental question, though, is whether NASA will solicit future SIMPLEx missions given the difficulties ESCAPADE, Janus, and Lunar Trailblazer have all faced. Glaze says she is interested, but it depends on a budget that is already strained with dealing with cost overruns and other problems with larger missions.

“I love the SIMPLEx program and I can’t wait to offer it again,” she said at a December town hall meeting. “But I need some budget.”

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.