The spaceport bottleneckby Tom Marotta

|

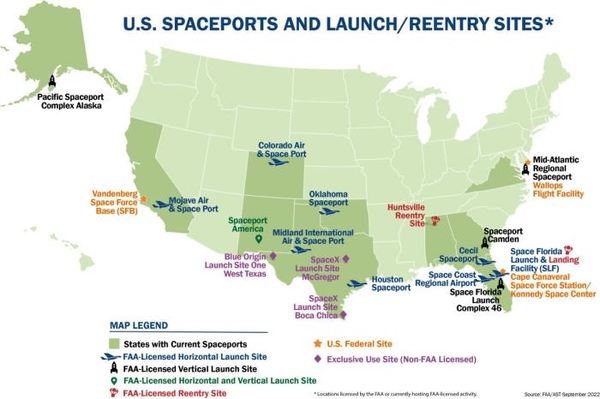

| America has more spaceports than any other country in the world — and more are planned — but most spaceports sit empty and unused. |

This, of course, is the dreaded traffic bottleneck. Drivers across the world are familiar with this phenomenon: a highway is built, vehicle traffic grows, and eventually the infrastructure reaches its capacity.

The American rocket-launching industry is experiencing something of its own bottleneck. There are more satellites and rockets being built today than ever before. But only a handful of US spaceports see the lion’s share of rocket launch activity. As a result, these sites are increasingly congested.

This is not, however, due to insufficient infrastructure. Indeed, America has more spaceports than any other country in the world—and more are planned—but most spaceports sit empty and unused. Why do rocket launching companies choose to “wait in traffic” for their turn to launch from one of the crowded sites when it seems they could use an “alternate route” and launch from a spaceport with available capacity? And why does it matter?

Demand for orbital launches is sky high

The answer as to why most rocket launches occur from only four congested US spaceports has to do with orbital mechanics and government regulation. Not all rocket launches are the same: some go to suborbital space while some go to orbital space. Most launch activity today involves sending satellites to orbit. This is because there is a strong demand for data from space. We are living in a golden age of satellite development. The US Federal Communications Commission, the regulator that doles out the radiofrequency spectrum that satellites use to transmit information back to Earth, received requests for 38,000 new satellites in 2021. If even half of these satellites are actually launched that would more than triple the number of active satellites in orbit today. Many of these satellites will be launched by SpaceX for their Starlink constellation. But many will not: an additional 1,700 small satellites are expected to be launched every year for the remainder of the decade.

The only known way to get a satellite into orbit is to use a rocket. There is a large and growing backlog of demand to get all these satellites to orbit and, as a result, there is a healthy demand for launch pads capable of sending a rocket to orbit.

A map of US licensed launch sites. Many inland spaceports have not hosted a launch and cannot support orbital launches. (credit: FAA) |

Launching to orbit from inland spaceports is not permitted

The US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulates non-governmental (i.e. commercial) rocket launches. The FAA’s job is to make sure the public is protected from the risk of rocket launches. After all, rockets are basically just giant tubes of explosives that are purposefully lit on fire and shot through the air. They are getting more reliable all the time, but mishaps are still quite frequent. The chance of any given rocket exploding and spreading thousands of pieces of fiery shrapnel falling to Earth is unnervingly high.

This is why all commercial rocket launches to date have launched from spaceports on the coast: if a rocket explodes over the ocean, it’s a lot less likely to hurt a person or damage personal property. Or, to put it another way, the reason a commercial rocket has never been approved to launch to orbit from an inland spaceport is that all rockets (to date) have been unable to meet the safety criteria required by the FAA. And the system is working: FAA has a perfect safety record when it comes to space travel. No member of the public has ever been hurt or killed from a commercial rocket launch. The FAA is very proud of this record and continues to do everything possible to maintain it. That is why the FAA is unlikely to relax its safety criteria.

| As congestion grows at existing sites and regulatory constraints impede inland launch, operating spaceports at sea becomes a more attractive option. |

So, will we ever see a rocket reliable enough to launch from an inland spaceport? Perhaps. Air travel was notoriously dangerous in the early years of flight but, with increasing experience, eventually became the safest mode of travel. The SpaceX Falcon 9 is the most prolific US launch vehicle in operation today, having launched over 100 times since its last mishap in 2016. However, while 100 launches is impressive, it is not nearly the level of activity necessary to demonstrate the reliability necessary to permit inland launches. For that we’d probably need to see several thousand successful launches which, at current levels of launch activity (61 launches in 2022, a record level), could take decades.

This is why SpaceX, and every other orbital rocket company, launches from one of four coastal spaceports in the United States: getting approval to launch to orbit from available inland spaceports is essentially impossible due to the excessive risk it poses to public safety.

Why does solving the spaceport bottleneck matter?

Our modern economy is heavily dependent on data services from space:

- World-spanning financial networks use precision timing services provided by the satellite-based Global Positioning System to synchronize financial transactions: literally trillions of dollars of global trade depend on reliable satellite communications.

- Increasing numbers of people access the Internet using bandwidth provided by satellites. This is especially important in areas of the developing world lacking terrestrial communications networks.

- The US Department of Defense purchases massive amounts of commercially-sourced satellite imagery to augment government-run surveillance capabilities. Many of the satellite photos of the Ukraine conflict that we see in the public media are provided by commercial firms selling the data to DoD.

- Commercial synthetic aperture radar, signals intelligence, weather forecasting, and numerous other data services are all improving knowledge of our environment and our economy, generating incredible wealth and scientific knowledge. We would not know about climate change without satellite networks.

Maintaining the satellite constellations that deliver this data from space requires smoothly operating spaceports capable of conducting regular launches to orbit.

Furthermore, data is fungible. There is very little preventing our adversaries from supplanting the Western firms that currently dominate the satellite data market with their own state-supported firms. They will do this in part by maximizing their own access to space by operating better spaceports. We are in a new space race and having a variety of paths to orbit is essential to remaining in the lead.

So, what’s the solution?

There are three viable paths to solve the spaceport bottleneck: build new spaceports on land in the US, launch from non-US spaceports overseas, or build spaceports on floating platforms at sea. Building new orbital spaceports in the US has proven difficult: all recent proposals have been delayed or permanently blocked by local community opposition. Operating rocket systems overseas requires obtaining export control approvals from the State Department, a process that can take years. It’s also very expensive to maintain supply chains to far-flung rocket sites outside of the US (or even inside the US.)

That leaves launching from the sea. Boeing successfully operated a sea-based launch site in collaboration with Russia for 15 years at the beginning of this century. That partnership became untenable when Russia invaded Crimea in 2014 and the system was subsequently abandoned. SpaceX is investigating offshore launch platforms for their new rocket system and South Korea tested an offshore rocket launch system in 2022. China currently operates two offshore spaceport infrastructure systems that are regularly used to send satellites to orbit.

As congestion grows at existing sites and regulatory constraints impede inland launch, operating spaceports at sea becomes a more attractive option to meet the demand for orbital launch, and solving the spaceport bottleneck.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.