The truth is up there: American spy balloons during the Cold Warby Dwayne A. Day

|

| In 1952, the RAND Corporation produced a study demonstrating that high-altitude balloons equipped with cameras could be useful for reconnaissance in areas where airplanes could not venture. |

But by the early 20th Century, improvements in aircraft technology rendered balloons increasingly obsolete for reconnaissance. During World War II fighter and bomber aircraft were converted to perform photographic reconnaissance missions. By late in the war, there were even proposals for dedicated fast propeller-driven reconnaissance aircraft like the Republic XF-12 Rainbow and the Hughes XF-11. But the dawn of jet aircraft meant that as new jets became available, they would eventually carry cameras. While this was happening, reconnaissance balloons made an unexpected comeback.

The technique for catching a payload falling under a parachute was first developed for recovering reconnaissance cameras and their film dropped from a balloon in the 1950s. This was later used for recovering film canisters returned from satellites from the 1960s into the 1980s. Here a practice payload is recovered by a US Air Force C-119 cargo plane, circa 1960. (credit: NRO) |

Balloons in the Cold War

Balloons became attractive for intelligence purposes again in the later 1940s. One project, known as Project Mogul, which was not declassified until the 1990s, involved carrying microphones to high altitude to detect the sound of nuclear explosions on the other side of the world. In 1947 , a Mogul balloon fell on a ranch near Roswell, New Mexico, spawning numerous conspiracy theories about extraterrestrials.

In 1952, the RAND Corporation produced a study demonstrating that high-altitude balloons equipped with cameras could be useful for reconnaissance in areas where airplanes could not venture. An overall research and development program was known as Project Moby Dick. By the later 1950s the Air Force and CIA cooperated on two audacious programs, known as GENETRIX and WS-461L, to carry sophisticated reconnaissance cameras over the Soviet Union.[1]

GENETRIX, also known as WS-119L (for “Weapon System”) was a direct outgrowth of Moby Dick. It initially started as Project GRANDSON, and by mid-1955 the plan was to procure 3,000 balloons, including 500 spares, to be launched at the rate of ten per day. The plan was to deploy balloons in western Europe and have them float over the Soviet Union. The payload consisted of two cameras looking downward to either side at a slight angle. The payload would be battery-powered and operated by a timer, and entirely at the mercy of the winds. Although the balloons would presumably be too high for the Soviets to attack during the day, they would cool at night and sink to lower altitudes, where they were vulnerable.

The Air Force expected that 75% of the 2,500 balloons would cross the Soviet Union, and that 40%, or 1,000 balloons, would be recovered. The prediction was that this would result in about 1.4 million photographs. Actual results were far less impressive.[2]

The key innovation for GENETRIX was the recovery method. At the end of the mission, while over the Pacific Ocean, the payload could be commanded to detach from the balloon and fall by parachute, where it would be captured in mid-air by a C-119 cargo aircraft towing a looped cable equipped with hooks that would snag the parachute lines. The payload, with its exposed film, would then be winched inside the airplane and flown back to an American facility where the film could be developed and analyzed. This recovery method was dicey, but Air Force pilots perfected it. The Air Force soon had contractors manufacturing hundreds of balloons and payloads for a massive overflight campaign.

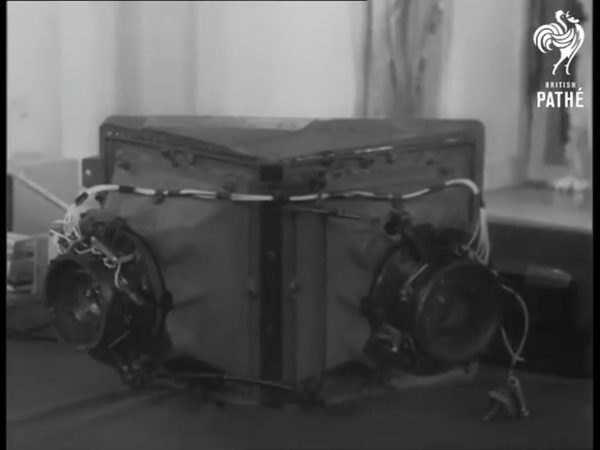

On December 27, 1955, President Eisenhower approved GENETRIX to conduct balloon overflights of the Soviet Union. Over a 27-day period in January and February 1956, 516 GENETRIX balloons were launched, floating up to altitudes of 16,750 meters. The Soviets were able to track them on radar. Only 44 payloads were recovered (less than 9% compared to the earlier prediction of 40%), and only 32 of these had useable photography. Most of the photos were of clouds, although there was some intelligence information gathered, particularly the discovery of a vast nuclear refining facility in Siberia known as Dodonovo. The Soviets recovered many balloons and their photographs and staged a public protest where they displayed many captured balloons and payloads. Eisenhower ordered an end to the program.[3]

Hundreds of American reconnaissance balloon payloads came down inside the Soviet Union during 1956. Project Genetrix was a political embarrassment for the United States. Note how many payloads are visible in this Soviet storage facility. (credit: British Pathé) |

By summer of 1956, the CIA began operating the U-2 reconnaissance aircraft. Intelligence officials believed that Soviet radars could not detect aircraft at the U-2’s operating altitude. They were immediately surprised when the first U-2 missions over eastern Europe were detected and Soviet air defense operators began talking about them on their radios, intercepted by western listening stations. President Eisenhower viewed the U-2 flights as highly provocative, equivalent to an act of war, and he insisted upon personally approving each mission, and over ensuing years the flights were rare, only a few per year.[4]

| Eisenhower “complained, in salty language, about the laxity in the defense forces—he said he would have, if he had done some of the things that have been done in the last few days—shot himself… The President suggested firing a few people—and said that people in the service either ought to obey orders or get the hell out of the service.” |

A couple of years after GENETRIX, the Air Force tried balloons again, this time with the WS-461L program. Meteorologists had noticed an unusual aspect of the jet stream. Most of the year it traveled from west to east over the Soviet Union. But during a six-week period in May and June, it traveled from west to east towards Alaska, and then climbed rapidly from 16,750 meters to 33,500 meters, reversed direction, and began flowing from east to west. Intelligence officials theorized that a balloon could travel this circular loop at altitudes so high it could not be detected on Soviet radars, and return a camera payload for recovery. They also suspected that the Soviet Union was unaware of this atmospheric phenomenon and would never be looking for a balloon flying from the east.[5]

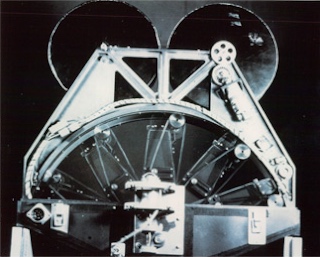

Whereas GENETRIX had introduced aerial recovery technology, WS-461L developed another important piece of technology: the panoramic camera. The camera, known as HYAC for “high acuity,” swept a 12-inch (30-centimeter) lens tube back and forth, exposing a curved strip of 70-mm film. This panoramic image could cover more ground below. One of the additional benefits of the design was that the highest quality image is produced near the center of a lens, not its edges, and the HYAC camera took advantage of this by exposing film using only the center part of the lens. The payload had to be insulated against the extreme cold at high altitude. Whereas the balloon and operations were covered by the Air Force, the CIA paid for the camera.[6]

This panoramic camera was developed for an American high-altitude reconnaissance balloon in the later 1950s. The same camera design was scaled up and adapted for the early CORONA reconnaissance satellites in the 1960s. (credit: NRO) |

Several dozen WS-461L camera systems were produced. On June 25, President Eisenhower approved the initial overflights, but concerned that the camera payloads could come down in Soviet territory, he ordered that the system not be equipped with a timer that would jettison the payload after a pre-set time. The Air Force disobeyed this order and kept the timers.[7]

On July 7, 1958, three balloons were launched off the deck of an aircraft carrier in the Bering Sea. The timers were set when the balloons were initially planned for deployment, but when their launch was delayed, the timers were not re-set. For several weeks there was no information about them, until July 28, when the Polish government complained about a camera-carrying balloon that had fallen in central Poland. The next day the Soviet Union protested about a balloon overflying its territory.

Historian Stephen Ambrose, writing in his biography of Eisenhower, explained how the president was furious and called the Pentagon. Unable to reach the Secretary of Defense, he got his deputy instead. Eisenhower “complained, in salty language, about the laxity in the defense forces—he said he would have, if he had done some of the things that have been done in the last few days—shot himself… The President suggested firing a few people—and said that people in the service either ought to obey orders or get the hell out of the service.”[8]

Eisenhower was angry about the WS-461L balloon flights, which he said in a memo were the result of “unauthorized decisions.” He also was mad about U-2 flights over routes “that contravened my standing orders.” Five days later, the Soviets again protested about the balloons, and Eisenhower was again furious.[9]

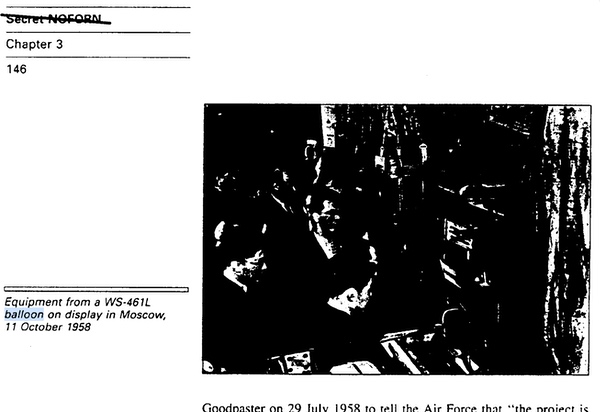

Besides the one recovered in Poland, which was eventually displayed in Moscow, another one of the WS-461L balloon payloads was found a year later in Iceland. It was possible that the third was recovered somewhere in the Soviet Union. The CIA assumed that because the payload was recovered, the Soviet Union was now aware of the design secrets of the panoramic camera.[10]

CIA historian Donald Welzenbach, writing in “Observation Balloons and Reconnaissance Satellites,” explained that the balloons were instrumental in the development of technology that was soon used in satellite reconnaissance programs. GENETRIX had developed the air-catch recovery system for the balloon payloads that was later used for CORONA, GAMBIT, and HEXAGON satellite film reentry vehicles. The WS-461L project developed the HYAC camera that was later scaled up to form the basis of the CORONA camera.[11] (Later, in the 1960s, the U-2 would also be used to carry satellite reentry vehicles to high altitudes to test their performance.)

This image was included in a declassified CIA history of the U-2 aircraft. It shows a WS-461L reconnaissance balloon camera that was recovered by the Soviet Union and displayed in Moscow in 1958. (credit: CIA) |

AKINDLE

In February 1959, President Eisenhower was briefed on the possibility that Soviet missile launches could be detected because of the existence of a “sound duct” that started at around 21,300 meters (70,000 feet) altitude and ran to 30,500–33,500 meters (100,000–110,000 feet). Because of a temperature inversion in this layer, sound tends to get trapped there, so a missile passing through it could be heard from far away. A balloon at that altitude with a listening device could detect a rocket engine, and with such balloons located at six points around the world the missiles could be located. One possible location for such a listening balloon was Asmara, Ethiopia, which was already the site of an American radio and signals intelligence facility.[12]

In March 1959, there was an internal CIA proposal for “a powered balloon as a high altitude platform for intelligence collection devices,” although it does not appear to have progressed beyond a proposal stage. This was probably connected to the “sound duct” balloon briefed to Eisenhower the previous month.[13]

American intelligence officials did not attempt any further balloon flights over the Soviet Union during Eisenhower’s term. However, during the Kennedy administration they revived the idea, initially for a balloon to collect signals from Soviet ballistic missile tests, and also for a high-altitude photographic balloon. Available documents refer to the former as an ELINT (for “electronic intelligence”) balloon, although ELINT usually referred to collecting radar data, and the goal was to collect missile telemetry (TELINT) data.

| American intelligence officials did not attempt any further balloon flights over the Soviet Union during Eisenhower’s term. However, during the Kennedy administration they revived the idea. |

The balloon program appears to have started by fall 1963 with a CIA document titled “Requirements for a balloon system vehicle.” The document stated the need to “safely and discretely carry a package of electronic equipment at high altitudes and over pre-planned flight paths.” The balloon would carry a payload weighing less than 4.5 kilograms (ten pounds) and about one cubic foot. The maximum flight time would be 36 hours, terminating at 24,400–27,400 meters (80,000–90,000 feet) during the daylight hours. The system should be simple enough to enable four to six balloons to be released in rapid or timed intervals. The launches would be conducted from cargo-type aircraft flying at altitudes ranging from 3,000–9,100 meters (10,000–30,000 feet).[14]

By early 1964, the CIA made a formal proposal to develop the system. The ELINT balloon program received the code-name AKINDLE. It resulted from both a requirement to obtain signals from Soviet ballistic missile tests inside the Soviet Union, as well as new technological developments both in balloons and electronics. New electronics technology made it possible to hide signals intelligence collection systems inside what looked like weather collection equipment, and intelligence officials believed that if a payload was retrieved in the Soviet Union, even on close examination it would appear to be a weather sensor. But the plan was to fly a small payload so high that it was never even detected.[15]

The specific missile system that attracted the CIA’s interest starting in 1963 is unclear, but was probably what eventually became known as the SS-9 in the West, with the Soviet designation of R-36. It was a big missile, equivalent to the American Titan II. National Security Agency ground stations on the periphery of the Soviet Union could collect intelligence on missiles in flight, but one of the goals was to collect the signals the missiles emitted before launch. The National Reconnaissance Office launched four PUNDIT satellites between 1963 and 1965 with the goal of collecting signals from Soviet missile launches, and later launched two SAVANT satellites with the same mission. But satellites in low orbits did not spend enough time over Soviet launch sites to collect this data, whereas a balloon could, although available documents do not indicate how the data would have been retrieved.[16] (See “Wizards redux: revisiting the P-11 signals intelligence satellites,” The Space Review, September 7, 2021; and “Stealing secrets from the ether: missile and satellite telemetry interception during the Cold War,” The Space Review, January 17, 2022.)

Whereas early overflights required presidential approval, by the early 1960s during the Kennedy and later administrations, a more regularized process was developed in the form of the “Special Group” created in the last years of the Eisenhower Administration and renamed the 303 Committee in 1964.[17] The 303 Committee was chaired by the president’s national security advisor, and had to approve requests for aerial overflights of foreign territory by piloted aircraft as well as drones. They were guided by two main principles: was the intelligence being sought really important, and was it worth the political risk?

In 1964, the CIA’s AKINDLE balloon program ran into strong headwinds with the 303 Committee, whose members made it clear that they would not approve any balloon overflights of the Soviet Union. By August, senior intelligence officials, including the Director of Central Intelligence John McCone, “discussed the futility of re-raising the proposal for balloon overflights.” [18]

In January 1965, the National Reconnaissance Office also sent the CIA the approved president’s budget for fiscal year 1966, which deleted any funding for the ELINT balloon and a “photo-balloon” program, although it is unclear where the decision to zero out funding for the balloon programs was made.[19] Existing documents do not indicate if the CIA even developed any operational hardware for the ELINT balloon.

Higher and higher

A July 1964 summary of CIA advanced aircraft missions referred to a balloon program that could achieve low vulnerability by reduction in detectability. It could be possible to maneuver by taking advantage of high-altitude winds. Potential missions could be “detailed reconnaissance of critical Soviet test sites; possibly also for order of battle and deployment reconnaissance of hot spots (e.g., Cuba).”[20]

| Whereas the reconnaissance balloon program was essentially dead by 1965, the United States still continued to use high-altitude balloons for research and development purposes. |

By April 1965, the CIA determined that it would be feasible to conduct balloon operations with a 11.3-kilogram (25-pound) payload at 33,500-meter (110,000-foot) altitudes, with both air launch and recovery of the payload. But very low temperatures at that altitude limited the system design because of the need for thermal insulation. However, the CIA also concluded that if a balloon could be flown at 45,700 meters (150,000 feet), the ambient air temperature was not as cold and a better system could be developed. It was even feasible to double the payload with further research and development.[21]

The CIA concluded that if a development program began in May, it could result in an operational vehicle capable of overflying the Soviet Union by July through September. “This would provide meteorological and operational data as well as firming the vehicle design data.”[22]

The limited number of declassified documents on AKINDLE do not provide any details, but indicate that CIA officials realized their proposals for high altitude reconnaissance balloons of any type were not going to be approved.[23]

By the late 1960s, the National Reconnaissance Office was testing large optical systems by carrying them to high altitudes over the Arizona desert. These tests provided information on what improved reconnaissance satellites could see from orbit. This payload was apparently flown around 1967. (credit: USAF (via Skeptical Inquirer magazine)) |

Photographic testing balloons

Whereas the reconnaissance balloon program was essentially dead by 1965, the United States still continued to use high-altitude balloons for research and development purposes. There is some evidence that CIA officials were considering a powered “photo-balloon” for intelligence collection missions at a “low-key effort” in April 1965.[24] However, there is evidence that the intelligence community was already doing tests of large optics systems carried by balloons in support of reconnaissance satellite research and development.

In 1963, scientist Sydney Drell led a study about what targets could be identified in aerial photographs taken at different ground resolution. Existing satellites like CORONA and GAMBIT had limited resolution, but higher-resolution systems were already in the planning stage, and using balloons to carry big cameras high into the atmosphere could assist engineers and scientists to determine the atmospheric limits on powerful cameras. Given the size of the payloads, there was no good way to conceal them from detection from ground-based radars, and these efforts were probably entirely for experimental purposes, not the development of a system to penetrate denied airspace.

According to one official account, “one result of the Drell Group study was a series of experiments in Arizona designed to determine if, under favorable conditions, the earth’s atmosphere would support overhead photography with resolutions as small as 5 cm (2 inches). In October 1964, a large balloon carried a 6-meter (240-inch) f/16.0 telescope with a camera attached to an altitude of 19,680 meters (65,000 feet) where it took photos with 5-cm resolution. Other flights, using a 1.7-meter (66-inch) f/5.0 camera system from the LANYARD project obtained photos with ground resolutions of 7 to 10 cm (3 to 4 inches).”[25]

In 1967 and 1969, the balloon experts flew very large cameras over Arizona, which one person estimated weighed between 2,722 and 3,629 kilograms, encased in three-meter cylinders. They were tracked by several helicopters carrying armed military police to surround the payload after landing. A photograph of one payload shows a large cylinder covered with solar cells. But there’s no further information on these tests, or any other discussion within the US intelligence community about high-altitude reconnaissance balloons. If any tests or further development took place in the 1970s, no information on them has been declassified.[26]

| Soviet military officials could have believed that the Americans were still planning to send spy balloons over their territory in the 1970s even if that was not actually happening. |

Throughout the latter half of the 1960s, the CIA apparently maintained an interest in a photo-balloon program. There are cryptic descriptions of goals for a balloon program capable of flying up to 45,700 meters (150,000 feet) in fiscal year 1966, increased to 53,300 meters (175,000 feet) in 1967 and 1968.[27] In 1969, there was a proposal for a photo-balloon reconnaissance system “capable of steerable and stationary flight up to 69,960 meters (200,000 feet) altitude carrying a useful payload. This capability can range from technical intelligence resolution to broad area coverage with a possibility of providing a real-time readout of the tactical situation in limited areas.”[28] Without further details, it is impossible to determine if the CIA was developing flight hardware, but the available documentation implies that this was only an ongoing R&D effort. The 303 Committee’s opposition was apparently still in place.

The Soviet M-17 Stratosphera aircraft was developed in the late 1970s to shoot down American reconnaissance balloons. Note the cannon on top of the aircraft. In the early 1980s, American reconnaissance satellites detected a laser mounted to a Soviet cargo aircraft, and the CIA received intelligence indicating that it was also intended to shoot down reconnaissance balloons. However, no American reconnaissance balloon programs from this era have been declassified, and the Soviets never publicly displayed any. They may have been paranoid about a threat that did not exist. (credit: Wikimedia Commons) |

Chasing ghosts?

There was, however, one later aspect of the Cold War that leaves some lingering questions. In the early 1980s some CIA intelligence analysts who focused on Soviet strategic weapons development were puzzled. Satellite photographs indicated that the Soviets had mounted a laser to the top of an Il-76 transport aircraft. The initial analysis was that the aircraft was for anti-missile tests. But a human source soon provided information that the aircraft was intended to destroy American reconnaissance balloons. In addition, the Soviets had also been developing the M-17 high-altitude aircraft that some later dubbed the “U-2ski” equipped with a cannon on its upper fuselage, also to shoot down American reconnaissance balloons. The problem was that as far as the CIA analysts knew, the United States had no spy balloons. So what had the Soviets so rattled that they were deploying weapons to counter it?

Throughout the Cold War it was common for the Soviet Union to develop weapons systems based upon a misunderstanding of the threat from the United States—just as it was common for the United States to do the same. Soviet military officials could have believed that the Americans were still planning to send spy balloons over their territory in the 1970s even if that was not actually happening. The heads of weapon design bureaus may have obtained approvals for these systems based upon fearmongering about stratospheric threats that never emerged. If the balloons were indeed there, and the Soviets shot any down, they never discussed or displayed them, even four decades later.

But as the recent experience with Killeen-23 demonstrates, the truth could be up there.

Endnotes

- W.W. Kellogg and S.M. Greenfield, “Revised Study of Pioneer Reconnaissance by Balloons,” RAND, RM-979, November 30, 1952; Curtis Peebles, The Moby Dick Project: Reconnaissance Balloons Over Russia, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991. Note: there were other RAND studies of balloon reconnaissance during the early 1950s.

- [Deleted author] Memorandum for: SA/PC/DCI – Mr. Bissell, “Aerial Reconnaissance of the U.S.S.R.,” n.d. but mid-1955. This document is a lengthy discussion of balloon, aerial, and satellite reconnaissance of the Soviet Union and predates both the U-2 and the CORONA reconnaissance satellite.

- Donald Welzenbach, “Observation Balloons and Reconnaissance Satellites,” Studies in Intelligence, 1986, pp. 23-24.

- Chris Pocock, Fifty Years of the U-2: The Complete Illustrated History of the Dragon Lady, Schiffer, 2005.

- Welzenbach, “Observation Balloons and Reconnaissance Satellites,” p. 24.

- Ibid.

- Gregory W. Pedlow and Donald E. Welzenbach, The Central Intelligence Agency and Overhead Reconnaissance: The U-2 and OXCART, History Staff, CIA, 1992, pp. 144-145.

- Stephen Ambrose, Eisenhower: Soldier and President, Simon and Shuster, 1991.

- Ibid.

- Albert D. Wheelon, Deputy Director for Science and Technology, Central Intelligence Agency, Memorandum for Director of Central Intelligence, “Further Comment on Loss of CORONA Cameras over China,” December 20, 1963. Wheelon was writing about the loss of CORONA cameras that had been adapted to fly on the U-2, several of which were shot down over China. He noted “Three of these cameras were lost in an Air Force balloon operation over the Soviet Union (the last of which was lost in March 1959) and are now on display in one of the Moscow museums.”

- Welzenbach, “Observation Balloons and Reconnaissance Satellites,” p. 28.

- Brigadier General Andrew J. Goodpaster, ”Memorandum of Conference with the President, February 10, 1959,” February 13, 1959.

- [no author] “The Feasibility of a Powered Balloon as a High Altitude Platform for Intelligence Collection Devices,” March 23, 1959. CREST

- “Requirements for a Balloon System Vehicle,” OSA-4467-63, September 24, 1963. CREST

- Albert D. Wheelon, Deputy Director for Science and Technology, Central Intelligence Agency, Memorandum for Director, National Reconnaissance Office, “Reconnaissance Using Balloons.” April 28, 1965. CREST

- Ibid.

- “Chronology of the 40 Committee,” n.d. (but probably February 1970), CREST. This document also includes “Evolution of the 40 Committee.” Together they provide a concise overview of this special advisory committee for coordinating covert operations.

- Walter Elder, “John A. McCone as the Director of Central Intelligence, 29 November 1961 – 28 April 1965,” March 1973, C06143459, p. 1402.

- Albert D. Wheelon, Deputy Director for Science and Technology, Central Intelligence Agency, Memorandum for Director of Central Intelligence, “CIA Reconnaissance Programs in FY66,” February 2, 1965, with attached: Brockway McMillan, Director, National Reconnaissance Office, Memorandum for Colonel Jack Ledford, Director, Program B, “F.Y. 1966 President’s Budget,” January 19, 1965. CREST

- [deleted author] Memorandum for the Record, “Advanced Aircraft Systems Missions,” July 13, 1964. CREST

- Albert D. Wheelon, Deputy Director for Science and Technology, Central Intelligence Agency, Memorandum for Director, National Reconnaissance Office, “Reconnaissance Using Balloons.” April 28, 1965. CREST

- Ibid.

- McCone, p. 1402.

- Albert D. Wheelon, Deputy Director for Science and Technology, Central Intelligence Agency, Memorandum for Director, National Reconnaissance Office, “Reconnaissance Using Balloons.” April 28, 1965. CREST

- Donald E. Welzenbach, “Project HEXAGON, Saved by SALT,” December 18, 1985, p. XI-7. LANYARD was a reconnaissance satellite that had been canceled in 1963. Several camera systems were left after the program ended.

- B.D. Gildenberg, “The Cold War’s Classified Skyhook Program.” Skeptical Inquirer, Volume 28, No. 3, May/June 2004.

- “Program Goals (FY 1966) Category: Photo Balloon,” n.d. Attached documents list the same program for 1967, 1969, and 1969. CREST

- “Program/Resources Forecast (FY 1969) Category: Balloon Reconnaissance.” CREST

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.