Touching spaceby Lisa Pettibone

|

| Why in the broad sweep of space exploration, as we reach further into the universe and consider living off planet, is it so important to make room for creative projects in future missions? |

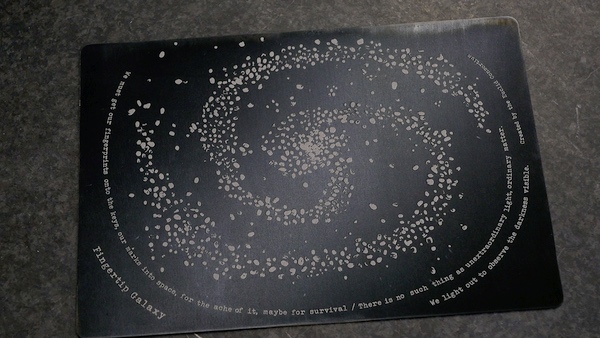

Mounted on its hull is the Fingertip Galaxy plaque with the finger marks of over 250 mission scientists and engineers, its goal to convey the spirit of the mission: a dedicated, and often personal, desire to unravel the structure of the universe through capturing images of billions of galaxies that point to the presence of dark matter. An international effort led by ESA, the initiative involves more than 1,700 people (including NASA astrophysicists) sharing their skills and determination to better understand the forces threading through space to almost three quarters back in time to the Big Bang.

The artwork comprises a handmade galaxy painting, surrounded by poetry related to its making, reduced and laser etched on to an aluminium A5-size plate and glued to the craft. Many of the scientists who worked with myself and Tom Kitching, the Euclid science lead, to achieve this effort were excited by the prospect of their marks going into space.

Perhaps unknowingly, their collaborative artwork joins a succession of creative space-based projects since the Apollo 12 mission in 1969, when artists Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol, among others, provided drawings transferred to a tiny ceramic chip that was smuggled on to the spacecraft. Usually, such artworks remain unacknowledged by launch officials, but for Euclid this unique painting had its own pre-launch campaign organised by mission manager Giuseppe Racca (whose fingertip was included) at Thales Alenia Space in Turin, Italy.

However, why in the broad sweep of space exploration, as we reach further into the universe and consider living off planet, is it so important to make room for creative projects in future missions? In the process of trying to answer this, we are compelled to review the importance of art to humanity in general—a subject copiously covered by art historians.

An expression of culture, thinking, and aesthetics, art is a vehicle to respond, expose, and process the world in which we live. In the context of space science, art touches on feelings and emotions not considered by science or technology. For example, Euclid’s data scientists have developed complex ways to measure galaxy distortions in order to map the structure of dark matter, but this won’t express the emotional experiences that drive their work. While artist-in-residence at Mullard Space Science Laboratory, I interviewed 13 members of the Visible Instrument team and many said the thrill of being involved in space exploration influenced their choice of work. The lure of the unknown, the romance of exploration, thirst for knowledge, call it what you want, but the emotional response is real and motivating. Their painted fingertips offered them a means to express the motive that underpinned years of research in an extremely demanding field.

A candid tweet during the launch by ESA Research Fellow Guadalupe Cañas-Herrera sheds light on the experience: “I doubted for days and Lisa pushed me to include my fingerprint on the last day (of the Helsinki Consortium meeting 2019). I thought I didn’t deserve it because I had just recently joined the EC Euclid team. Years later, I’m happy I did. Too emotional.”

| Would it be possible to add an “aesthetic intervention” that signified the personal contributions of the Euclid team, the culture of the people who made it? What if other beings found the telescope in thousands of years, what messages would it carry? |

In general, my role was to help many scientists overcome their hesitancy to get involved. Many felt that “art” wasn’t for them and needed convincing. At the Euclid Consortium meeting at the University of Helsinki, I laid out a large white sheet across two tables in the conference lobby, with the faintest of pencil lines as a guide, and asked people to join me in making a galaxy with black painted fingertips. It was slow going at first and Tom enlisted me to run up the stairs to an open area, where people were having coffee between talks, to let everyone know about our unique project. As the number of participants and enthusiasm swelled during the morning, it became easier to convince others to take part.

When ESA confirmed that the artwork would indeed be put on the spacecraft, this news was like moths to a flame—the table became a hive of activity and a social gathering place. Many confided that they hadn’t done any art in years. And here may be the rub: often scientists leave the trappings (and joy) of art behind with their childhood. As professionals with exacting disciplines, mixing creativity with scientific concepts was foreign, an unsettling mix. Artists, however, see a way around this, embracing the cultural activity of science in the arms of creativity. More scientists are becoming open to the stimulating mix of art/science relationships, the trick is finding them.

I was therefore fortunate to meet Tom Kitching, professor of astrophysics at University College London’s MSSL Space Laboratory, who enthusiastically accepted my proposal to be artist-in-residence when I completed an MA in Art and Science at Central Saint Martins London 2018. I was researching the aesthetics of gravity and, curious about the concept of gravitational lensing, I contacted him. Our many philosophically tinged conversations about dark matter and perception led to an unexpected outcome for the Euclid mission and a burst of creative activities at the lab that are still talked about. Imaginative, drop-in workshops during lunch hours in their common room included glass fusing (I make glass sculpture), cyanotype prints, pinhole cameras, painting and visits by other artists.

Usually present two days a week, I shared my developing work as I responded to scientific concepts and laboratory environments, all embellished by casual conversations and reading. The year-long residency also resulted in staff presentations, a film, a symposium, and a final exhibition in London in 2019. Art had snuck in through the back door of MSSL, held open by two curious people (who happen to have very different jobs) with a love for astrophysics. Institutional support was essential: Arts Council England’s Lottery Grant funded this extraordinary collaboration; later, as the project grew and was better understood, it was supplemented by MSSL and ESA, who invited me to visit them in the Netherlands.

The germination of the Fingertip Galaxy project came at a key moment about halfway through the residency. During one of our regular talks, I mentioned to Tom that the spacecraft seemed devoid of creative design features and lacked the human touch. I was thinking of the lavishly engraved and bejewelled astrolabes and sextants I’d seen in London’s Science Museum and Royal Society collections. Would it be possible to add an “aesthetic intervention” that signified the personal contributions of the Euclid team, the culture of the people who made it? What if other beings found the telescope in thousands of years, what messages would it carry?

| This is why it is crucial to include artists in space missions, to leave room for the unexpected merging of ideas and inspiring outcomes these can provide. Unique perspectives are achieved only when the full breadth of humanity is drawn on through poetry and art. |

Tom jumped at this thought and spontaneously sent a rough proposal to ESA. Perhaps primed by his interactions with poet-in-residence Simon Barraclough several years before that resulted in a compendium of poems by MSSL staff, he saw the benefit of including the humanities in space science programs. Next, brainstorming sessions unearthed the nugget of a concept: a collaborative artwork centred around a spiral galaxy shape. Feeling a need to research the topic, I showed him other space-related projects, including a concept by digital artist Eyal Gever to produce 3D sculptures on the ISS generated from the sound waves of human laughter. Crucially, we also spoke of the primitive cave drawings at Lascaux where handprints clearly showed an expressive human presence. We asked ourselves, haven’t people always left intentional marks where they have lived or explored? Simon said it best in the Euclid poem “Unextraordinary Light” commissioned to surround the Fingertip Galaxy: “We must get our fingerprints onto the keys, paddle and daub the musical stave, get our notes, our marks into space. For the hell of it. For the ache of it. Maybe for survival.”

There is a school of thought that believes art and science aren’t natural bedfellows, that it’s an anomaly that such relationships develop at all. This leaves us staring at a crucial misconception about humanity: are our minds bent solely toward ordered reason or attuned to expressiveness? Humans hold both qualities but choose (or are nudged by society) to cultivate one over the other in their work over time while developing creativity for different ends. Science is incredibly creative and innovative. Leaps of intuition backed by years of research result in most technological and theoretical breakthroughs. Driven by curiosity and combined with intense powers of observation and determination, artists find ways to embody and express the extraordinary. But try swapping these descriptions for both professions: they work because we share more than sum of our differences. Together we carry the spectrum of humanity in our work.

This is why it is crucial to include artists in space missions, to leave room for the unexpected merging of ideas and inspiring outcomes these can provide. Unique perspectives are achieved only when the full breadth of humanity is drawn on through poetry and art. The public can enter the mind of both scientist and artist and find a way into increasingly complex endeavours, coming away with an emotional link to new concepts and prompting fresh engagement with some of the most existential questions of our time. How did we get here and how do we go forward? The scientists who put their mark on the Fingertip Galaxy knew intuitively that they wanted to be part of that unified future.

The Euclid Mission successfully launched on July 1, 2023, from Cape Canaveral on a Falcon 9 rocket to its L2 orbit. A consortium of approximately 3,500 scientists and engineers from around the world (including NASA) are involved in the mission to explore the dark universe.

A film about the Fingertip Galaxy project and information about Lisa’s residency at MSSL is available. Lisa Pettibone’s artwork Verdant was included in the Moon Gallery ISS Test Mission in 2022-23, sending 64 artists into orbit, the first gallery in space.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.