Dark territory: the National Reconnaissance Office, satellite inspection, and anti-satellite weapons in the early 1970sby Dwayne A. Day

|

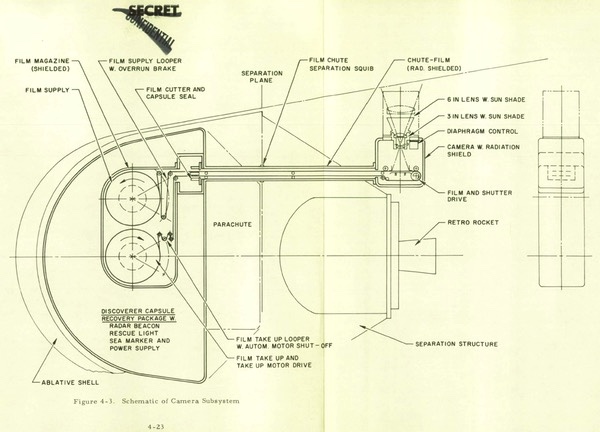

Previously unpublished photo of a Program 437AP inspector spacecraft atop a Thor rocket at Johnston Island in the mid-1960s. The 437AP was equipped with a camera for photographing other satellites. It was a variant of the 437 nuclear-armed anti-satellite weapon, which was retired by the early 1970s. In 1972, the National Reconnaissance Office, which managed the United States' fleet of reconnaissance and intelligence satellites, considered whether to pursue a satellite inspection capability that had thorny international and government implications. (credit: USAF via Dwayne Day collection) |

Alternative payloads

Throughout the 1960s, the United States pursued several projects to develop both anti-satellite (ASAT) and inspection satellite capabilities, ultimately resulting in the nuclear-armed Program 437 ASAT, which became operational in 1964. Program 437 had two active launch pads on Johnston Island—also known as Johnston Atoll—located several hundred kilometers southwest of the Hawaiian Islands.

Program 437 also briefly included an inspection capability, the mysterious Program 437AP, for “alternative payload.” The inspection satellite followed a ballistic trajectory, not entering orbit, taking pictures on film that was returned to Earth for later processing. The Air Force conducted three test flights of 437AP, with one success, but the program was discontinued. Although the history of American ASAT programs during the Cold War has been explored by several historians over the decades, there are still significant gaps in the record. For example, no photo of the 437AP equipment has ever been released by the Air Force.

| The policy questions associated with doing this were huge: not only the international implications, but whether an agency dedicated to gathering intelligence about adversaries on the ground and at sea should also become involved in close operations against other satellites. |

Recently, the NRO declassified a document that adds a new footnote to the history, indicating that in 1972 the agency considered developing a satellite inspection capability. The document is a memorandum for the National Reconnaissance Program Executive Committee (ExCom) raising several issues for discussion at an upcoming meeting. One of those issues was “the NRO role in a satellite inspection/negation program.” The ExCom consisted of high-level CIA and DoD officials who oversaw the NRO, which at that time provided the bulk of intelligence collected about American adversaries. Every week, NRO satellites took thousands of photos of the Soviet Union, China, and other countries, and gathered radar and other signals that provided tremendous insight into their capabilities and actions. But satellite inspection was not an NRO mission.

By 1972, the Soviet Union had demonstrated a non-nuclear anti-satellite system. “This already extensive and growing capability clearly constitutes a serious threat to the National Reconnaissance Program as well as most other U.S. satellite programs,” the memo’s author wrote. The memo indicated that the Soviet satellite, which entered into the same orbit as its target before firing an explosive charge to destroy it, may have been optimized to attack NRO photo-reconnaissance satellites.

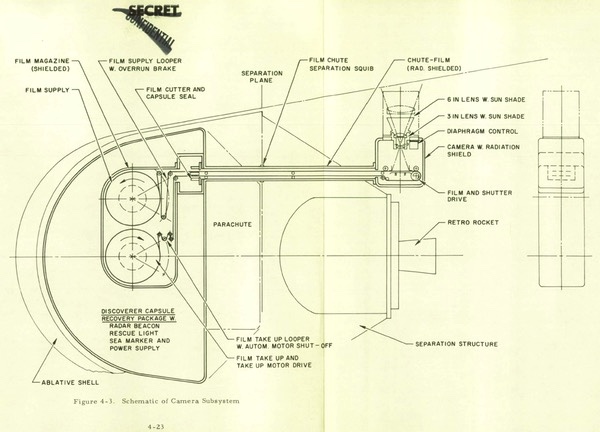

In the mid-1960s, a contractor proposed an orbiting inspector satellite that would be equipped with sensors for evaluating other spacecraft. It was not developed. (credit: USAF) |

Inspection, negation, and surveillance

According to the memo, since 1962, the United States had spent about $700 million “on satellite inspection, negation, and surveillance systems,” with about $200 million of that spent on studies, technology programs, and subsequently canceled system projects. Most of the rest was spent to improve space tracking systems and the Program 437 ASAT.

Program 437 was not an ideal ASAT. Despite having a one-megaton nuclear warhead, it had low accuracy because it lacked a terminal guidance system. It also had location and resource drawbacks. The Thor missiles that launched the ASAT were being used up by the Air Force during the 1960s, most of them converted to launch spacecraft. There was also the ever-present possibility that a storm could severely damage the incredibly flat Johnston Island launch site.

Using the ASAT could have major consequences. “The actual use of our nuclear interception system would not only violate the treaty against nuclear tests in space, but would as well seriously damage or disable much of the U.S. space inventory,” the March 1972 memo noted. By 1970, the program was put in standby status until it was finally ended in 1974 and removed from the island by 1975 (see “To attack or deter? The role of anti-satellite weapons,” The Space Review, April 20, 2020.) This planned retirement, along with the Soviet Union’s demonstrated capability, prompted new thinking about an American ASAT capability.

In late 1971, Radio Corporation of America (RCA), which built civilian and military weather satellites, proposed “a low-cost demonstration flight vehicle to perform an inspection and negation mission.” It would use flight-qualified hardware and be a relatively inexpensive, low-risk program. It would rely on a television camera and recorder system that could provide many high resolution images of the target. RCA’s proposal was probably not the best possible operational system, but could be “a good candidate for a low-cost demonstration only.”

| The NRO was a unique agency that incorporated the CIA and the military, but it was not a warfighting organization. Satellite inspection, and certainly satellite negation, were both “a new area of endeavor outside” of the organization’s charter. |

The Soviet Union knew that the United States had a nuclear ASAT capability and was certainly capable of developing a non-nuclear satellite inspection/negation system. If the United States pursued RCA’s demonstration mission, “the deterrent value of such a system would certainly be much greater if the Soviets remained convinced that a capability, once perceived, remains in being, ready to be used at the President’s option.” This would require that “security must be very tight to protect the ‘empty pipeline’ behind the demonstration.” The NRO had tighter security than the Air Force, and would be a good option for maintaining the secret that, when it came to an American ASAT, the emperor had no clothes.

There was no consensus within the US government about the need for a new ASAT capability and whether it should be classified or unclassified. The NRO was a unique agency that incorporated the CIA and the military, but it was not a warfighting organization. Satellite inspection, and certainly satellite negation, were both “a new area of endeavor outside” of the organization’s charter, although demonstrating this capability “might serve as a deterrent” to protect the NRO’s own satellites “whose vehicles are prime targets.”

Although the specifics of the ExCom discussion in early 1972 are unknown, it apparently led nowhere. The ASAT issue was taken up within the White House’s National Security Council in following years, and many of those discussions have been declassified and discussed by historians. A resumption of Soviet ASAT tests in 1976, as well as increasing Soviet satellite capabilities, led to further discussions in Washington about the need for an American ASAT, both as a deterrent and offensive capability. Ultimately, the Ford Administration, and later the Reagan Administration, chose to develop an overt ASAT capability within the Air Force, a system that was tested in the 1980s but never pursued to full-scale operation due to its cost. Despite the NRO not getting involved in the “satellite inspection” mission, by 1973 the NRO developed the capability to image other satellites at hundreds of kilometers using its reconnaissance satellites, a highly-secret, but far-less threatening mission. (See “Saving Skylab the top secret way,” The Space Review, May 22, 2023.)

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.