Review: From the Laboratory to the Moonby Jeff Foust

|

| While at White Sands preparing for a launch, a secretary came in at the end of the workday and told him it was five o’clock. “AM or PM?” he responded. |

The renaming is fitting. George R. Carruthers, the namesake of the spacecraft, studied the geocorona during his long career at the Naval Research Lab (NRL). He led development of a telescope, placed on the lunar surface during the Apollo 16 mission, that provided the first images of the geocorona from space. That work generated significant publicity for him, but only in part because of the science: Carruthers was the rare Black scientist working in the space program at the time.

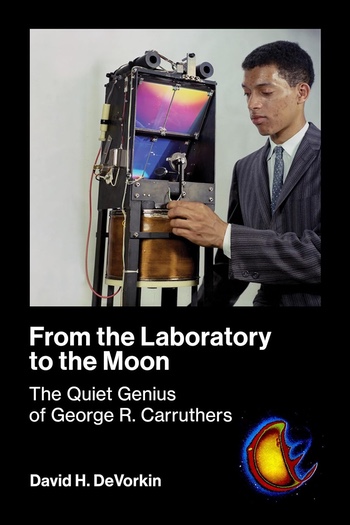

In From the Laboratory to the Moon, David DeVorkin, senior curator emeritus at the National Air and Space Museum, provides a thorough biography of Carruthers. His work on Apollo 16 was just part of his career that started by pioneering new technologies in ultraviolet observations from sounding rockets. He worked for decades in the field, becoming widely regarded, particularly among his colleagues at NRL.

That alone would likely not make him worthy of a 450-page biography. However, Carruthers started his career in an era where there were very few other Black scientists in the field. Even at college at the University of Illinois just after Sputnik, he was one of the few, if not the only, Black student in his science and engineering classes. He became a role model, and for much of the later years of his career devoted considerable time to educational outreach.

DeVorkin notes that Carruthers did experience discrimination, yet “there is no evidence, however, that it ever had an influence on his early life or career.” Indeed, he seemed able to shrug off what he did experience. In one example, a person comes to NRL to interview for a jab and mistakes Carruthers—dressed casually, as was often the case when working his lab—as a janitor. Carruthers laughs it off: “I dress like one, so everybody usually thinks I am.”

| Even in biographical interviews with DeVorkin and others, Carruthers “maintained his distance” and said little about his feelings about critical moments in his life. |

That may be linked to an intensity he showed in his work, dating back to college, shutting out everything else to focus on the task at hand. He arrived at the lab early and left late, and frequently worked weekends. While at White Sands preparing for a launch, a secretary came in at the end of the workday and told him it was five o’clock. “AM or PM?” he responded.

The book is more of a professional history of Carruthers, in part because he said little about his personal life. DeVorkin writes that because of Carruthers’s reserve, “his voice is heard here less than the author wished.” Even in biographical interviews with DeVorkin and others, Carruthers “maintained his distance” and said little about his feelings about critical moments in his life. That included his decision to apply to become a NASA astronaut, one of thousands of candidates for the famous 1978 class. He had the technical qualifications, but it would also mean ending his research at NRL he was so dedicated to. DeVorkin concludes that his decision to apply has no “simple summation” but instead reflected his passions for both spaceflight and his research. (Carruthers was medically disqualified because of a vision issue.)

Despite his groundbreaking work in ultraviolet astronomy in his early career, including the Apollo 16 telescope, his research faded later as his technologies were superseded by new ones, such as CCDs. Near the end of his career, as NRL dealt with limited office space in Washington, Carruthers’s lab was moved into a trailer outside the building where he had been for decades, but he continued work there, even after formally retiring from NRL. He remained fully engaged in educational work, though, until his health declined in his later years. He died in 2020.

Should George Carruthers be better known today for his research accomplishes, educational outreach and as a role model? That’s hard to say, and after reading From the Laboratory to the Moon it’s clear his private nature likely contributed to a lack of greater awareness. But with book and, in a few months, the launch of the Carruthers Geocorona Observatory, it’s worth reexamining his life and his contributions to science and society.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.