Starship setbacks and strategiesby Jeff Foust

|

| SpaceX said before the latest launch that Flight 8 failed for different reasons than for Flight 7, despite losing the vehicle at nearly the same time in its ascent. |

The attention was off what happened a few days earlier in Starbase, Texas, with the latest test flight of SpaceX’s Starship vehicle. The May 27 test flight was intended to demonstrate that the company had resolved the problems that caused the loss of the Starship upper stage, or ship, on the previous two launches in January and March. But it revealed other problems with the vehicle that cast new doubts on its ability to achieve its Moon and Mars milestones on schedules laid out by the company and, in the case of lunar missions, expected by NASA.

The Flight 9 mission launched after getting final safety approvals from the FAA days earlier, although without the completion of the mishap investigation into Flight 8 in March. (Flight 8 itself took place under similar circumstances, with the investigation into Flight 7 not closed until late March.) SpaceX said before the latest launch that Flight 8 failed for different reasons than for Flight 7, despite losing the vehicle at nearly the same time in its ascent.

In the case of Flight 8, SpaceX said one of the center Raptor engines in Starship suffered a hardware failure, details of which the company did not disclose. That caused “inadvertent propellant mixing and ignition” which led to the loss of that Raptor as well as three other engines. That was different from Flight 7, when engines shut down after a stronger-than-expected harmonic response created fuel leaks that fed a fire in the engine bay.

On Flight 9, the ship completed its full burn, placing the vehicle on a planned suborbital trajectory that would lead to a reentry and “soft” splashdown in the Indian Ocean. However, shortly after engine shutdown the ship appeared to be venting propellants and going into a slow roll. A planned opening of a payload bay door, enabling the release of eight Starlink mass simulators, did not occur.

SpaceX only acknowledged the problems with Starship about half an hour after liftoff. “We are in a little bit of a spin. We did spring a leak in some of the fuel tank systems inside of Starship,” Dan Huot, a host of the SpaceX webcast of the launch, said. “At this point, we’ve essentially lost our attitude control with Starship.”

SpaceX called off another test planned for the flight, an in-space relight of a Raptor engine, and instead worked to passivate the vehicle, preparing for an uncontrolled reentry. Without attitude control, the ship could not properly orient itself for reentry, and intermittent video returned by the vehicle showed damage as unprotected parts of it heated up. Telemetry was lost from the vehicle about 47 minutes after liftoff, and SpaceX declared the mission over.

On test flights, success and failure come in many shades of gray. There were clearly some successes on Flight 9, such as addressing, to some degree, the problems on the previous two flights. The Super Heavy booster on Flight 9 was the first such booster to be reused, having first flown on Flight 7. SpaceX said before the launch that a “large majority” of its components had previously down, including 29 of its 33 Raptors. (SpaceX deliberately did not attempt to catch Super Heavy on this flight, instead putting it through a series of deliberately stressing maneuvers after the ship separated, with the booster lost during its landing burn offshore from Starbase.)

| “Leaks caused loss of main tank pressure during the coast and re-entry phase. Lot of good data to review,” said Musk. |

Yet, Flight 9 was the third Starship test flight in a row to fail to even attempt a controlled reentry and soft splashdown. The company had been making largely steady progress on the first six flights, to the point where it had demonstrated the ability to do precision soft splashdowns in the Indian Ocean while catching the Super Heavy booster back at the pad, but a switch to a new version of the vehicle starting with Flight 7 appears to have tripped up the company.

“Leaks caused loss of main tank pressure during the coast and re-entry phase. Lot of good data to review,” Elon Musk posted on social media shortly after the loss of Starship on Flight 9. “Launch cadence for next 3 flights will be faster, at approximately 1 every 3 to 4 weeks.”

That cadence, though, will likely depend on the ability of SpaceX to complete the mishaps reviews for both Flights 8 and 9. The FAA said May 30 that it would require a mishap investigation for the Starship upper stage on Flight 9 because it did not complete its mission as planned. No investigation, though, will be needed for Super Heavy because the loss of the booster “is covered by one of the approved test induced damage exceptions requested by SpaceX for certain flight events and system components,” the FAA stated.

Despite recent setbacks, Musk said there was still a “50-50” chance SpaceX could launch Starships to Mars—with Tesla’s Optimus robots on board—in the next Mars launch window in late 2026. (credit: SpaceX) |

Musk’s Starship game plan

The Flight 9 mission was noteworthy for another reason: Musk said before the launch he would provide an update on Starship development before the scheduled liftoff. However, a planned live event about six hours before launch was called off by SpaceX and Musk for reasons the company did not disclose, with Musk saying he would wait until after the flight. Shortly after the loss of Starship on Flight 9, the social media post advertising the event was taken down.

Instead, SpaceX posted May 29 an update that Musk provided at an unspecified date and time at Starbase. There was no discussion about the Flight 9 failure as Musk instead looked ahead to a future—a near future, he argued—where Starship launches were commonplace.

On one level, the talk was something of a greatest-hits speech by Musk, hitting themes he has long talked about like making humanity multiplanetary by establishing a self-sustaining city on Mars. He also expressed support for a “Moonbase” as well, echoing comments from a 2017 talk when the vehicle was still known as BFR (see “Mars mission sequels”, The Space Review, October 2, 2017) and expected to be going to Mars by now.

Musk did spend time talking about technical aspects of Starship. That included upgrades to the Raptor engine, designated version 3, with changes such as doing away with a base heat shield to reduce mass. “It’ll take probably a few kicks of the can,” he said, “but it is a massive increase in payload capability, in engine efficiency, and in reliability.” He went so far as to call the engine “alien technology.”

| “This is an important technology, which we should hopefully demonstrate next year,” Musk said. if in-space refueling. |

Despite the setback on Flight 9, Musk sounded optimistic about not just returning the Starship upper stage intact, but performing a catch landing at the launch site like SpaceX has demonstrated with Super Heavy. “That’s what we hope to demonstrate later this year,” he said after showing an animation of a ship being caught by a launch tower at Starbase. “Maybe as soon as two or three months from now.”

But elsewhere in the talk he appeared to quietly acknowledge delays in Starship’s development. One key technical milestone is demonstrating in-space propellant transfer, with one Starship docking with another in low Earth orbit to transfer methane and liquid oxygen. A year ago, NASA officials said they expected that first in-space propellant transfer—a key step needed for Starship’s use as an Artemis lunar lander—to take place in early 2025.

That clearly has not happened, and Musk indicated it would not happen at all this year. “This is an important technology, which we should hopefully demonstrate next year,” he said.

Despite delays in demonstrating propellant transfer in orbit, Musk offered an aggressive schedule for Starship missions to Mars. That included attempting to send Starships to Mars when the next window opens in late 2026. “We’ll try to make that opportunity if we get lucky. I think we probably have a 50-50 chance right now because we’ve got to figure out orbital refilling.”

Those Mars missions, if they do launch, would be “min viable vehicles with goal of maximizing learning,” a chart he displayed in his talk stated. Musk said the Starships may carry versions of Optimus, a humanoid robot being developed by Tesla. “That would be a very cool image if we were able to achieve it,” he said, showing an illustration of a robot walking on Mars with Starships in the background.

A chart from Musk’s talk showing the company’s plans to dramatically ramp up launches to Mars. (credit: SpaceX) |

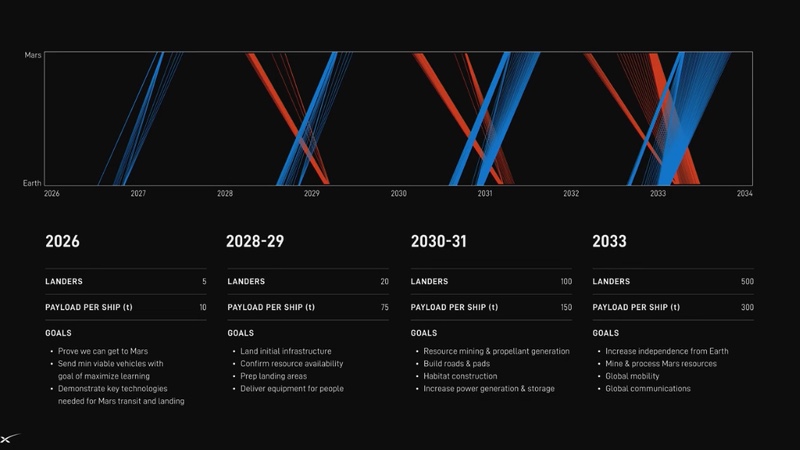

Musk said his “tentative game plan” calls for a dramatic increase in Starship missions to launch to Mars in each window, from five in the 2026 window to 20 in the 2028–2029 window, then 100 in 2030–2031 and 500 in 2033. The payload in each lander would also sharply increase, from 10 tons per lander in 2026 to 300 tons in 2033.

That is driven by Musk’s believe that one million tons of cargo needs to be delivered to Mars for a self-sustaining base to become a reality, an estimate he acknowledged could be low by an order of magnitude or more. He went so far in the talk to identify his preferred location on Mars to establish that base, the Arcadia Planitia region in the northern mid-latitude regions, based on characteristics like flat terrain and access to water ice.

That will require a tremendous number of launches. Each Mars-bound Starship will need multiple launches to be fully fueled for the trip to Mars; Musk did not disclose how many but with 500 landers projected in 2033 it will mean thousands of launches, timed to enable those 500 landers to take off for Mars within several weeks of each other when the window is open. Musk compared that vision to the fleet of ships jumping into hyperspace on Battlestar Galactica, and admitted it creates other problems, like having enough landing pads for those 500 landers when they arrive Mars. “We’ll solve that problem later.”

To enable that high launch rate, Musk said SpaceX is working to be able to turn around the Super Heavy booster within an hour or two of landing—a period comparable to commercial airliners despite the less stressing environments for those planes and far greater operational experience—and developing a factory capable of producing a thousand Starship ships annually, or three a day.

| “Starlink internet is what’s being used to help pay for humanity getting to Mars,” Musk said, thanking Starlink customers “for helping secure the future of civilization and helping make life multiplanetary.” |

Notably, other than his aside about creating a “Moonbase Alpha,” there was no discussion about how NASA’s Artemis lunar exploration campaign fits into those plans, even though SpaceX has $4 billion in NASA awards to develop a lunar lander version of Starship and transport astronauts to and from the lunar surface on Artemis 3 and 4. With an in-space propellant transfer test pushed back to next year, having Starship ready for the Artemis 3 landing in 2027—which requires SpaceX to conduct an uncrewed landing beforehand—looks increasing challenging to achieve.

Musk also didn’t talk about what else Starship would do, although he’s made clear that a key mission will be launching new, larger Starlink satellites to increase the capacity of that broadband constellation, providing a funding stream for Mars. “Starlink internet is what’s being used to help pay for humanity getting to Mars,” he said, thanking Starlink customers “for helping secure the future of civilization and helping make life multiplanetary.”

Unlike some past talks, he didn't discuss Starship’s role in point-to-point terrestrial transportation or other applications. The overall Starship system will have to surge to meet Musk’s vision of launching hundreds of vehicles to Mars once every 26 months, but it’s not clear how heavily the fleet will be utilized the rest of that time, which prompts questions of the ability to do that surge when needed.

Musk, of course, is known for his aspirational schedules: in that 2017 talk, for example, he talked about sending cargo to Mars in 2022 and crew in 2024. He admits that those schedules could slip while remaining optimistic about the overall approach of sending massive numbers of vehicles to Mars in the relatively near future. It remains to be seen, though, if the recent problems with Starship are a blip that will be forgotten or a harbinger of deeper problems that put Musk’s vision in question.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.