Taiwan’s satellites: A lawfare vulnerability and an option to cure and enhance deterrence against the PRC (part 1)by Michael J. Listner

|

| Taiwan’s legal standing and by extension the legal status of its satellites contain a troubling lawfare weakness that could be exploited by the PRC to diminish or nullify the use of these satellites. |

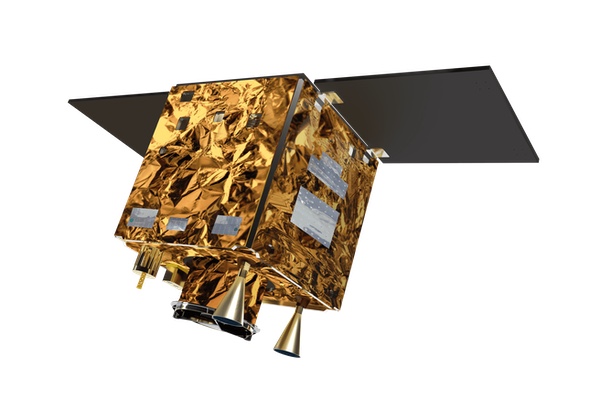

Taiwan’s satellite fleet is small with a little more than 20 satellites in orbit, including the FORMOSAT-7/Triton weather satellite launched on October 9, 2023.[2] Taiwan’s satellite fleet is set to be bolstered with the FORMOSAT-8 program, which will provide a remote sensing capability for Taiwan. The FORMOSAT-8 program is a priority mission as part of Taiwan’s 3rd Phase space program. The FORMOSAT-8 program will consist of six high-resolution optical remote sensing satellites in Sun-synchronous orbit to provide sub-meter resolution through ground post-processing. The first of the satellites is expected to be launched by the end of 2025.[3]

Yet, Taiwan’s legal standing and by extension the legal status of its satellites contain a troubling lawfare weakness that could be exploited by the PRC to diminish or nullify the use of these satellites by Taiwan and even allow the PRC to extend its sovereignty over the satellites in the lead-up to an invasion or blockading of the island. Notably, Taiwan’s dilemma presents an opportunity for the United States to enhance its policy and relationship with Taiwan and gain a strategic advantage over the PRC in great power competition. The US can achieve this by employing lawfare to exploit a legal right granted by international outer space law to emulate a Reagan-era maritime policy to “flag” certain of satellites launched for Taiwan by the US and place then under the ownership and jurisdiction of the US. and hence create a legal barrier to interference by the PRC.

This three-part article will briefly unpack Taiwan’s legal standing, discuss the applicable space, Taiwan’s present standing or lack of legal standing in outer space law, and how that absence of legal standing creates a lawfare weakness that could be exploited against its current fleet of satellites. It will introduce the reader to the concept of hybrid warfare and specifically lawfare and elaborate on how the US could make a policy decision to execute a lawfare operation that would cede legal jurisdiction and control of Taiwan’s satellites to the US and by extension grant those satellites legal protection under international law.

Customary international law and Taiwan’s legal status

The question of Taiwan’s legal status and autonomy is one that continues to be a key point of contention in diplomatic relations between the US and the PRC. For its part, Taiwan’s present legal status is the product of two resolutions by the United Nations General Assembly. Those two resolutions rendered Taiwan to its status are declarative in that they make declarations or determinations of principles of international law.[4] When a declaratory resolution is passed by a unanimous or near-unanimous vote, the resolution is deemed by some to create the presumption the principles within the declaration hold the status of customary international law.[5]

The legal test for customary international law consists of two components: “First, there must be a general and consistent practice of states. This does not mean that the practice must be universally followed; rather it should reflect wide acceptance among the states particularly involved in the relevant activity. Second, there must be a sense of legal obligation, or opinio juris sive necessitatis. In other words, a practice that is generally followed but which states feel legally free to disregard does not contribute to customary law; rather, there must be a sense of legal obligation. States must follow the practice because they believe it is required by international law, not merely because that they think it is a good idea, or politically useful, or otherwise desirable.”[6] Additionally, “Not all states are equal from that perspective. State practice and opinio juris of states which occupy a special and outstanding position in the field at issue are of more value than those of other states.”[7]

While declaratory resolutions are presumed to hold the status of customary international law, that presumption can be overcome by evidence of significant state practice or principle of international law that is contrary to the principle within the declaration.[8] The importance of this exception will be discussed in the context of the legal remedy to overcome the legal exposure to Taiwan’s satellites later in this article.

Applying this principle, the Republic of China held the legal status of a sovereign state under international law until the People’s Republic of China invoked UN Resolution 1668 on October 25, 1971. UN Resolution 1668 recognizes, when a founding member of the UN brings into dispute the governing authority of another member, that issue should be taken into consideration in light of the principles of the UN Charter.[9] UN Resolution 1668, which as a declarative resolution arguably having the standing of customary international law, provided the PRC legal standing to challenge the ROC’s sovereignty. That challenge resulted in UN Resolution 2758, which passed in the General Assembly on July 15, 1971, and likewise as a declarative resolution has the potential standing as customary international law and gave formal recognition to the People’s Republic of China as the legitimate representative for China to the UN. This removed the ROC’s representative to the UN and removed the ROC’s status as a sovereign state.[10]

US policy towards Taiwan after UN Resolution 2758

After UN Resolution 2758, US policy towards Taiwan took shape and was formed through over three presidencies and the enactment of federal law by Congress: Three Joint Communiqués, the Taiwan Relations Act, and the Six Assurances.[11]

| It is this legal conundrum of Taiwan’s status as a non-State that is significant to the potential lawfare vulnerability to its satellites. |

For its part, the Taiwan Relations Act was Congress’s response to the severance of diplomatic relations with Taiwan after the Joint Communiqué on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations.[12] The Act stipulates the policy of the US to maintain relations with both Taiwan and the PRC, declares peace in the region in the interests of the US, stipulates diplomatic relations with the PRC are contingent on the future of Taiwan being determined by peaceful means, to provide arms to Taiwan for defense, and maintain the capacity for the US to resist any force or coercion against Taiwan.[13] Significantly for the purposes of this article, Section 3303 obligates the US to treat Taiwan like a State under the law regardless of the lack of diplomatic relations and despite UN Resolution 2758. In other words, Taiwan is a State for purposes of the Taiwan Relations Act and federal law in general.

The crux of US policy is this: Taiwan is not recognized as a sovereign State, which effectively makes it a non-State. The US recognizes Taiwan’s “sovereignty” only to the extent to its right to self-government consistent with the Taiwan Relations Act, the Three Joint Communiqués and the Six Assurances. Otherwise, US policy does not recognize Taiwan’s independence, nor does it encourage it.[14] It is this legal conundrum of Taiwan’s status as a non-State that is significant to the potential lawfare vulnerability to its satellites.

Pertinent provisions of outer space law

The corpus of outer space law is embodied in international law and finds its genesis in both customary international law and treaties.[15] Article 38(1) of the Statute of the International Court of Justice recognizes that international law derives from international conventions, international custom, and general principles of law.”[16]

The first norm of customary intentional law for outer space was created from the ideal of free passage in outer space espoused by the Eisenhower Administration. Prior to the launch of Sputnik-1, the Soviet Union did not limit its sovereignty to the stratosphere and regarded outer space above its territory part of its sovereign control.[17] The launch of Sputnik-1 challenged this claim of sovereignty as Sputnik-1 would be clearly violating the “territory” of other states under the Soviet theory. The Soviets tried to explain Sputnik-1 had not violated the territory of other states as it did not pass over the territory of those nations, but rather the territories of other states passed beneath Sputnik.[18] This explanation was rejected and did not gain footing as customary international law.

The Eisenhower Administration took the occasion of the launch of Sputnik-1 to meet its policy objective of free passage through outer space and establish a norm of customary international law.[19]

The lack of objection by States to the overflight of their territories by Sputnik-1 met the threshold required to assert the norm of customary international law for the free passage of outer space has been created and was recognized as binding. This was exemplified by Eisenhower Administration in a memorandum dated October 10, 1957, from the 339th Meeting of the National Security Council:

“Another of our objectives in the earth satellite program was to establish the principle of the freedom of outer space—that is, the international rather than the national character of outer space. In this respect the Soviets have now proved very helpful. Their earth satellite has overflown practically every nation on earth, and there have thus far been no protests.”[20]

Sputnik-1’s launch and overflight were only the beginning of the creation of customary law for outer space. The establishment of customary norm of free access was complemented when the UN General Assembly adopted the Declaration of Legal Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space.[21] As a declarative resolution the Declaration of Principles have the standing of customary international law.[22] These principles, along with the customary norm of free access, formed the foundation of the international space law treaties, particularly the Outer Space Treaty.

The breadth of the body of treaty law making up international space law is beyond the scope of this discussion and will instead focus on pertinent provisions of two treaties: the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space (Outer Space Treaty or OST) and one of its progeny, the Convention of Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space (the Registration Convention).

There are two provisions of the OST germane to the discussion at hand: Article VI and Article VIII.

| The Soviets tried to explain Sputnik-1 had not violated the territory of other states as it did not pass over the territory of those nations, but rather the territories of other states passed beneath Sputnik. |

Article VI stipulates: “States Parties to the Treaty shall bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, whether such activities are carried on by governmental agencies or by non-governmental entities, and for assuring that national activities are carried out in conformity with the provisions set forth in the present Treaty. The activities of non-governmental entities in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, shall require authorization and continuing supervision by the appropriate State Party to the Treaty. When activities are carried on in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, by an international organization, responsibility for compliance with this Treaty shall be borne both by the international organization and by the States Parties to the Treaty participating in such organization.”[23]

“National activities” in Article VI refers to activities that have some special connection with the State.[24] These activities are conducted by the State itself through either governmental agencies or by non-governmental entities for their own account.[25] The non-governmental allowance in Article VI represents a compromise between the Soviet Union and the US where the Soviet Union wanted to exclude non-governmentals and make outer space exclusive to State activities.[26] This effectively absorbs non-governmental activities into governmental activities and, by extension, national activities.[27] Article VI expressly requires “authorization and continuing supervision” by the “appropriate State Party.”[28] Determining the “appropriate State Party” for non-governmentals may seem straightforward given the language of Article VI but in practice can be otherwise.[29] The overall effect of Article VI is to directly implicate States for the activities of non-governmentals under its jurisdiction and control.[30]

Article VII of the OST concerns liability, and the language is taken from the Soviet draft of the OST, which in turn was based on Paragraph 8 of the Declaration of Principles.[31] Article VI of the OST states: “Each State Party to the Treaty that launches or procures the launching of an object into outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, and each State Party from whose territory or facility an object is launched, is internationally liable for damage to another State Party to the Treaty or to its natural or juridical persons by such object or its component parts on the Earth, in air space or in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies.”[32] Article VII, for its part, establishes a general principle for liability for national space activities. It served as a stopgap measure for the Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects, which was in the process of drafting by the Legal Subcommittee.[33] Because the issue of liability was being developed in the new treaty, a general principle allowed for inclusion of liability in the OST without preempting the progress being made by the Subcommittee.[34]

Article VIII states: “A State Party to the Treaty on whose registry an object launched into outer space is carried shall retain jurisdiction and control over such object, and over any personnel thereof, while in outer space or on a celestial body. Ownership of objects launched into outer space, including objects landed or constructed on a celestial body, and of their component parts, is not affected by their presence in outer space or on a celestial body or by their return to the Earth. Such objects or component parts found beyond the limits of the State Party to the Treaty on whose registry they are carried shall be returned to that State Party, which shall, upon request, furnish identifying data prior to their return.”[35]

Article VIII establishes “continuing jurisdiction and control” over objects and personnel launched into space during a national activity in outer space and on a celestial body, and it imposes a legal obligation to return objects registered to a State Party.[36] Significantly, Article VIII points to a national registry, which is emphasized in one of the OST’s children. Arguably, Article VIII creates sovereignty and by extension sovereign immunity of a State Party over objects and personnel launched into space. This includes objects launched by non-governmentals who are performing national activities under the authorization and continuing supervision of a State.[37] Indeed, this interpretation of sovereignty in Article VIII appears to be held out by the US via state practice.

The Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations recognizes the principle of sovereignty over space objects in Article VIII:

“Sunken warships, naval craft, military aircraft, government spacecraft, and all other sovereign immune objects retain their sovereign-immune status and remain the property of the flag State until title is formally relinquished or abandoned, whether the cause of the sinking was through accident or enemy action—unless the warship or aircraft was captured before it sank.”[38]

The state practice of asserting sovereign immunity and hence ownership over government spacecraft is a statement of customary international law regarding Article VIII by the US and is thus open to interpretation.[39] Nonetheless, the special and outstanding position of the US not only in the maritime domain but outer space as well enhances its intent to be legally bound by this state practice and consequently makes a strong case for what appears to be the US interpretation of Article VIII.[40] It’s noteworthy the Handbook does not mention non-governmental spacecraft, but the practical application of the principle to non-governmental spacecraft is implicit as non-governmental space activities are amalgamated to governmental space activities and considered national activities under Article VI.[41] For purposes of this discussion, the author applies the customary law position of sovereignty in Article VIII that has been adopted by the US.

The second space law treaty that is relevant to this discussion is the Convention on the Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space. Pertinent to this discussion is Article I, Article II, Article III, and Article IV. Each is examined below.

Article I(a) of the Registration Convention defines the term “launching State” as follows:

“For the purposes of this Convention: a) The term "launching State" means: (i) A State which launches or procures the launching of a space object; (ii) A State from whose territory or facility a space object is launched.”[42]

Article I(a) of the Registration Convention builds upon Article VIII of the OST, where the State who built the space object or the State that launched the space object could be considered the launching state and hence the state who can exercise jurisdiction and control and hence sovereignty over the space object.[43] Notably, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 59/115, which relates to findings related to the term “launching State” and made recommendations to States related to reporting under both the Registration Convention and the Liability Convention.[44] The Resolution explicitly states it was not intended an authoritative interpretation of or a proposed amendment to the Registration Convention or the Liability Convention, which means it does not have standing as customary international law but is hortatory.[45]

Article I also defines the term “space object”, which “includes component parts of a space object as well as its launch vehicle and parts thereof…”[46] Article I(c) leads into Article II by defining the term “State of registry” as: “…a launching State on whose registry a space object is carried in accordance with Article II.”

| The state practice of asserting sovereign immunity and hence ownership over government spacecraft is a statement of customary international law regarding Article VIII by the US and is thus open to interpretation. |

Article II of the Registration Convention requires a State who is identified as the “launching State” to register the space object in a national registry, which [the State] has established.[47] This is the registry envisioned in Article VIII of the OST.[48] The contents and the means of maintaining the registry is left up to the State.[49] Article II next addresses the situation where two or more States could qualify as the launching State under Article I(a). Article II(2) directs the States to jointly determine who will exercise jurisdiction and control and be considered the launching State and register the object in their national registry and the registry created in Article III.[5-] This process has been validated through state practice. The third provision of the Registration Convention that is relevant to this discussion is Article III. Article III stipulates: “The Secretary-General of the United Nations shall maintain a Register in which the information furnished in accordance with article IV shall be recorded.”[51]

The contents of the Register are stated in Article IV(1):

“Each State of registry shall furnish to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, as soon as practicable, the following information concerning each space object carried on its registry: (a) name of launching State or States; (b) an appropriate designator of the space object or its registration number; (c) date and territory or location of launch; (d) basic orbital parameters, including: (i) nodal period; (ii) inclination; (iii) apogee; (iv) perigee;(e) general function of the space object.”[52] The Register is maintained by the UN Office of Outer Space Affairs as the Register of Space Objects.[53]

The Registration Convention is an extension of Article VIII of the OST that identifies the launching State and sovereignty through jurisdiction and control and the requirement of the national registry to certify that sovereignty. This is key to the dilemma with Taiwan’s satellites and the legal remedy to cure that deficiency.

It is judicious before closing this section to mention the Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects.[54] The Liability Convention is not just an extension of Article VII of the OST; it is fulfillment of Article VII. As previously mentioned, the Liability Convention was in the process of being drafted during negotiations for the OST with Article VII being a stopgap measure.[55] The Liability Convention’s relevance for this discussion is limited to acknowledging the definition of the term launching State, which is found in Article I(c). The term launching State in the Liability Convention is identical to the definition found in Article I(a) of the Registration Convention. Although the two definitions are identical, they are not interchangeable as each is designated for the treaty they are contained within. Accordingly, the term “launching State” in the Liability Convention will have no bearing on the discussion in this article.

References

- Xi Jinping's '37-year plan' for Taiwan reunification: Attacks on the mind and a looming crisis, Nikkei Asia, November 1, 2022.

- Gunter’s Space Page, TRITON(FORMOSAT-7).

- Taiwan Space Agency, FORMOSAT-8.

- Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Directorate, Legal Effect of United Nations Resolutions Under International and Domestic Law, 4, LL File No. 2015-012099 LRA-D-PUB-000467 (2015).

- Id.

- United States v. Bellaizac-Hurtado, 700 F.3d 1245, 1252 (11th Cir. 2012). “…customary international law is the “general and consistent practice of states followed by them from a sense of legal obligation…” Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations § 102(2) (1987).

- Frans G. von der Dunk, “THE DELIMITATION OF OUTER SPACE REVISITED: The Role of National Space Laws in the Delimitation Issue,” Proceedings of the Forty-First Colloquium on the Law of Outer Space (1998), 254,

- Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Directorate, Legal Effect of United Nations Resolutions Under International and Domestic Law, 4, LL File No. 2015-012099 LRA-D-PUB-000467 (2015).

- UN Resolution 1668, Representation of China in the United Nations, 1080th plenary meeting, December 15, 1961.

- UN Resolution 2758, Restoration of the lawful rights of the People's Republic of China in the United Nations, 1976th plenary meeting, October 25, 1971.

- In Focus, President Reagan’s Six Assurances to Taiwan, Congressional Research Service, March 28, 2024.

- Taiwan Relations Act, 22 U.S.C. § 3301(a).

- Taiwan Relations Act, 22 U.S.C. § 3301(b).

- There appears to have been a modification to the U.S. stated policy towards Taiwan under the Administration of President Donald J. Trump where the Department of State removed the phrase “U.S. does “not support Taiwan independence,” Omitting this phrase is contrary to the wishes of the PRC. Whether this is a bell weather to change in U.S. policy towards Taiwan remains to be seen. Department of State, U.S. Relations With Taiwan: Bilateral Relations Fact Sheet.

- Domestic space law plays a large role in shaping international space law; however, international law remains the foundation.

- International Court of Justice, Statute of the International Court of Justice, art. 38(1).

- Delbert R. Terrill, Jr., “The Air Force Role in Developing International Space Law,” Air University Press, May 1999, 27-28.

- Terrill, Jr., 30.

- “A customary international law norm will not form if specially affected States have not consented to its development through state practice consistent with the proposed norm.” Bellaizac-Hurtado. at 1255 citing North Sea Continental Shelf Cases (Fed. Republic of Ger. v. Den.; Fed. Republic of Ger. v. Neth.), 1969 I.C.J. 3, 43 (Feb. 20).

- Everett S. Gleason, Memorandum: Discussion of the 339th Meeting of the National Security Council, October 10, 1957, State Department, Office of the Historian, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955–1957, United Nations and General International Matters, Volume XI.

- UN General Assembly, Declaration of Legal Principles Governing the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, 18th Session, 1280th Plenary Meeting (December 13, 1963).

- Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Directorate, Legal Effect of United Nations Resolutions Under International and Domestic Law, 4, LL File No. 2015-012099 LRA-D-PUB-000467 (2015).

- UN: Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, October 10, 1967, art. vi, 18 UST 2410.

- Bin Cheng, Article VI of the 1967 Space Treaty Revisited: “International Responsibility”, “National Activities”, and the Appropriate State, Journal of Space Law, 20, Volume 26, Number 1, 1998.

- Cheng, Article VI, 20.

- Cheng, 20.

- Cheng, 14.

- Cheng, 26.

- Cheng, 26.

- Cheng, 15.

- Paul G. Dembling and Daniel M. Arons, “The Evolution of the Outer Space Treaty,” Journal of Air Law and Commerce 33 (1967), 437.

- UN: Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, October 10, 1967, art. vii, 18 UST 2410.

- Dembling and Arons, 438.

- Id.

- UN: Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, October 10, 1967, art. viii, 18 UST 2410.

- Dembling and Arons, 439-440.

- Cheng, 14. UN: Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, October 10, 1967, art. vi, 18 UST 2410.

- The Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations, 2022, Chapter 2.1.2..

- Publications like the recently available Woomera Manual on the International Law of Military Space Activities and Operations have a broader view of “ownership” with regards to Article VIII that is the result of consensus and not state interest.

- Frans G. von der Dunk, “THE DELIMITATION OF OUTER SPACE REVISITED: The Role of National Space Laws in the Delimitation Issue,” Proceedings of the Forty-First Colloquium on the Law of Outer Space (1998), 254,

- Cheng, 14.

- UN: Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, art. i(a), November 12, 1974, 1023 U.N.T.S. 15.

- “The term “space object" includes component parts of a space object as well as its launch vehicle and parts thereof;” UN: Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, art. i(b), November 12, 1974, 1023 U.N.T.S. 15.

- UN General Assembly, Application of the concept of the “launching State”, Res. 59/115, January 25, 2005.

- Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Directorate, Legal Effect of United Nations Resolutions Under International and Domestic Law, 4, LL File No. 2015-012099 LRA-D-PUB-000467 (2015).

- UN: Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, art. i(b), November 12, 1974, 1023 U.N.T.S. 15.

- UN: Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, art. ii(1), November 12, 1974, 1023 U.N.T.S. 15.

- UN: Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, October 10, 1967, art. viii, 18 UST 2410.

- UN: Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, art. ii(3), November 12, 1974, 1023 U.N.T.S. 15.

- UN: Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, art. ii(2), November 12, 1974, 1023 U.N.T.S. 15.

- UN: Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, art. iii(1) November 12, 1974, 1023 U.N.T.S. 15.

- UN: Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, art. iv(1) November 12, 1974, 1023 U.N.T.S. 15.

- UN Office of Outer Space Affairs, United Nations Register of Objects Launched into Outer Space.

- Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects, 24 UST 2389, September 1, 1972.

- Dembling and Arons, 438.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.