Taiwan’s satellites: A lawfare vulnerability and an option to cure and enhance deterrence against the PRC (part 2)by Michael J. Listner

|

| Taiwan’s legal recognition of international space law is moot from the perspective of the international community, including its self-professed legal obligations under the OST. |

By extension, Taiwan’s legal status prevents it from becoming a party to the Registration Convention and the resultant rights and duties within, including ownership of objects launched into space on the behalf of Taiwan. It is the loss of these legal rights and its succession of those rights to the PRC, along with the PRC’s standing as a party to the Registration Convention, that is significant to the vulnerability of Taiwan’s satellites to hybrid warfare, and particularly lawfare. However, as will be discussed later in this article, the Taiwan Relations Act has the effect of recognizing Taiwan’s continuing legal obligations in the eyes of US law, which will be key to the solution to this lawfare dilemma.

The PRC, The Three Warfares, and lawfare

Warfare is traditionally linked to open conflicts, employing force through physical means to achieve military objectives and by extension political objectives. However, great power competition with the PRC, the Russian Federation and its proxies coupled with the specter of nuclear weapons has made hybrid warfare useful tools in today’s complex geopolitical environment. In this multifaceted geopolitical environment, long-established means of employing force through physical means as enunciated by Clausewitz is not always a viable option and where hybrid warfare becomes significant.[6]

Xu Sanfei, the editor of Military Forum and a senior editor in the Theory Department of Liberation Army News explains that hybrid warfare:

“…refers to an act of war that is conducted at the strategic level; that comprehensively employs political, economic, military, diplomatic, public opinion, legal, and other such means; whose boundaries are blurrier, whose forces are more diverse, whose form is more mixed, whose regulation and control is more flexible, and whose objectives are more concealed.”[7]

This vision of hybrid warfare is manifested in the PRC doctrine of The Three Warfares. Andrew Marshall, the former Director of the Office of Net Assessment, commissioned a report on the Three Warfares. The report elaborates:

“The Three Warfares is a dynamic three-dimensional war-fighting process that constitutes war by other means. Flexible and nuanced, it reflects innovation and is informed by CCP control and direction.”[8] “The Three Warfares envisions results in longer time frames and its impacts are measured by different criteria; its goals seek to alter the strategic environment in a way that renders kinetic engagement irrational.”[9]

The concept of the Three Warfares was approved by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Central Committee, and the Central Military Commission (CMC) in 2003.[10] The CMC created the Three Warfares for the PLA to wage informational warfare concept to influence key areas of competition in its favor.[11] The 2011 Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China notes the Three Warfares “reflects China’s desire to effectively exploit these force enablers in the run up to and during hostilities. During military training and exercises, PLA troops employ the ―three warfares to undermine the spirit and ideological commitment of the adversary. In essence, it is a non-military tool used to advance or catalyze a military objective.”[12]

The Three Warfares is couched in terms of a military doctrine, but its true nature is political consistent with Clausewitz’s observation: “[t]he political object-the original motive for the war-will thus determine both the military objective to be reached and the amount of effort it requires.” [13]

In other words, the Three Warfares are intended to influence political outcomes not just military objectives.

The Three Warfares applies psychological warfare, legal warfare, and media warfare. The triad of the Three Warfares can be applied individually but more often in combination with one or more of its aspects. This paper will elaborate on legal warfare, or lawfare, as it is relevant to the issue of Taiwan’s satellites.

The concept of legal warfare or lawfare did not originate with the Three Warfares. The first known exercise of legal warfare dates to the 17th century with Hugo Grotius, who is known as the progenitor of international law, in his work Mare Liberum (The Freedom of the Seas), which was published in 1609. Grotius was commissioned by the Dutch East India Company in 1607 to make the case that the sea is common to all and all nations are free to use the seas for trade.[14]

The term “lawfare” was first coined and defined by Maj. Gen. Charles J. Dunlap, Jr., USAF (retired) in 2001 as: “…a method of warfare where law is used as a means of realizing a military objective.”[15]

General Dunlap’s definition of lawfare emphasizes the purpose of legal warfare as achieving a military object and not a political object as remarked by Clausewitz: “The political object-the original motive for the war-will thus determine both the military objective to be reached and the amount of effort it requires.”[16]

Indeed, the perception that the Three Warfares is a tool to achieve military objectives is similarly flawed as it overlooks the true objective is political. Another definition of lawfare is offered by Dr. Jill Goldenziel as:

“…the purposeful use of law taken toward a particular adversary with the goal of achieving a particular strategic, operational, or tactical objective, or 2) the purposeful use of law to bolster the legitimacy of one’s own strategic, operational, or tactical objectives toward a particular adversary, or to weaken the legitimacy of a particular adversary’s particular strategic, operational, or tactical objectives.”[17]

Like General Dunlap’s definition, Dr. Goldenziel’s definition of lawfare also focuses on the military objective and discounts the political object noted by Clausewitz.

“Lawfare” is more precisely defined by this author as follows: “The application of the rule of law and its instruments and institutions as force to augment or replace physical force to serve a national interest or achieve a political/geopolitical end.”[18]

This definition of lawfare is strategic and recognizes the object of lawfare is not military but a means to a political end or state interest. In this context law becomes force, which substitutes or supplements physical force to achieve the political object and bears out Clausewitz’s observation about force: “War is thus an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will.”[19]

It is in the context of this definition of lawfare the vulnerabilities to Taiwan’s satellites and a potential strategy that can be applied to not only cure this vulnerability but also strengthen the standing of the US in great power competition will be discussed.

Legal status of Taiwan’s satellites, lawfare, and vulnerabilities

UN Resolution 2758 and the declarations made by the PRC when it acceded to the OST divested Taiwan of any legal standing in international law, including outer space law. Taiwan is no longer a Party to the OST and accordingly does not have the legal right to retain jurisdiction and control over satellites it launches through outside parties such as the United States. UN Resolution 2758 and the PRC’s accession to the OST and Taiwan’s subsequent expulsion from the OST means Taiwan is also excluded from joining the Convention on the Registration of Objects Launched Into Outer Space. Thus, its status as non-State means it cannot be considered a “launching State” per Article I(a).[20]

| An article in the Taipei Times broke the story that satellites launched for Taiwan were listed in the Register of Space Objects as “Taiwan, Province of China”. |

There is an argument most provisions of the OST, including Article VIII, have become not only customary international law but norms of customary international law.[21] If this is the case, Taiwan could try to assert customary international law to benefit from the jurisdiction and control provisions of Article VIII of the OST even though it is no longer a Member State to the UN or a party to the OST.[22] However, Taiwan’s legal status as a non-State epitomized by UN Resolution 2758 precludes Taiwan from asserting standing under customary international law.

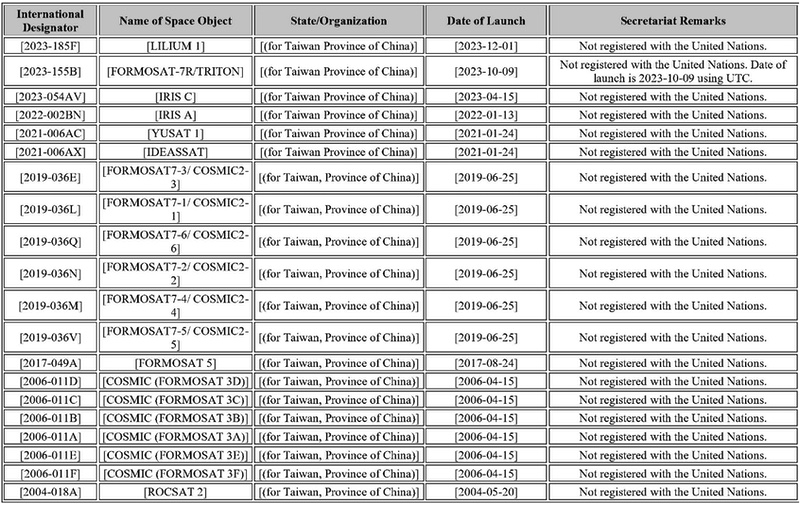

Taiwan does not have a domestic launch capability and relies on other states such as the US to launch its satellites. Twenty-five satellites have been launched for Taiwan, but none of them have been registered with the Office of Outer Space Affairs for inclusion in the Article III Registry of Space Objects nor has Taiwan attempted to do so.[23] Even though Taiwan has not sought to register its satellites in the Article III Registry of Space Objects in the UN they have been listed albeit by an unknown procedure.[24]

An article in the Taipei Times broke the story that satellites launched for Taiwan were listed in the Register of Space Objects as “Taiwan, Province of China”, but it is significant the satellites have not been registered with the name of the launching State in the Article III Register of Space Objects.[25] For its part, Taiwan cannot be recognized as the launching State in the Article III Register of Space Objects because of its status as a non-State under UN Resolution 2758.[26]

The following table in Figure 1 is a sampling from a search of the UNOOSA database that lists the satellites launched for Taiwan that remain in orbit.[27] The results of the search using the term “Taiwan” are listed as “for Taiwan Province of China” and notably not registered with the United Nations.

Figure 1[28] |

According to the Taipei Times, Taiwan has never filed a registration with the UN Office of Outer Space Affairs.[29] This is not unusual given Taiwan is legally a non-State, no longer a Member of the UN after UN Resolution 2758, and its status as party to the OST has been abrogated, which means it follows over to the other space law treaties, including the Registration Convention. The effect is even if Taiwan attempted to make a filing, it would likely be rebuffed because of UN Resolution 2758.[30]

The question then is how did these satellites end up listed in the Register of Space Objects, why are they listed as “for Taiwan, Province of China”, and who requested these entries be made? “The office might have its own agenda for collecting the information, but Taiwan was never informed, he said, adding that a registration with other agencies is also not compulsory,” the Taipei Times reported.[31] If this is the case, then the Office of Outer Space Affairs may have created an administrative process on its own for Taiwan’s satellites that automatically lists Taiwan as “Taiwan, Province of China” consistent with the UN’s removal of Taiwan via UN Resolution 2758.[32]

Alternatively, the possibility exists the PRC has an ongoing lawfare operation in the Office of Outer Space Affairs to list Taiwan’s satellites as such. Some would argue there is little hard evidence to support the existence of a PRC lawfare action within the Office of Outer Space Affairs to list Taiwan’s satellites as such. Yet, a lawfare operation that results in the listing of Taiwan’s satellites as “Taiwan, Province of China” in the Register of Space Objects would clearly benefit the PRC’s national interests and political goals towards Taiwan and would be consistent with the Three Warfares. This at the very list gives credence to consider the possibility instead of outright rejecting it.

Regardless of why or how the entries were made into the Register of Space Objects, it is evident this has become at least an administrative practice by the Office of Outer Space Affairs where future satellites launched for or by Taiwan will be listed but not registered into the Register of Space Objects denoting the satellites as a “Taiwan, Province of China.” In doing so, whether by fluke or by craft, a lawfare vulnerability for Taiwan’s satellites has been created that further dilutes Taiwan’s claim of autonomy from the PRC and creates exposure to Taiwan’s satellites to additional lawfare actions that would directly benefit the PRC’s political goals vis-à-vis Taiwan. In turn, this lawfare vulnerability could be exploit in multiple scenarios for not only Taiwan’s current satellites but with the yet-to-be launched FORMOSAT-8 series of satellites as well. Four potential scenarios are discussed below.

Taiwan’s satellites and lawfare vulnerabilities

Irrespective of whether the entry of Taiwan’s satellites as “Taiwan, Province of China” in the Register of Space Objects was done arbitrarily by the Office of Outer Space Affairs or as part of a directed lawfare operation by the PRC, the end result is to create exposure to Taiwan’s satellites to additional lawfare actions that would directly benefit the PRC’s political goals vis-à-vis Taiwan.

The cumulative effect of UN Resolution 2758, Taiwan’s expulsion from the OST, its lack of standing to assert customary international law, and the listing of its satellites as “Taiwan, Province of China,” brings into question whether Taiwan can assert jurisdiction and control over these satellites.[33] This in turn creates a lawfare vulnerability the PRC could exploit in multiple scenarios not only with Taiwan’s current satellites but with the yet-to-be launched FORMOSAT-8 series of satellites as well, as discussed below.

Scenario 1

The PRC could capitalize on the lawfare weakness of the listing of Taiwan’s satellites as “Taiwan, Province of China” and a lack of a launching State to further delegitimize Taiwan’s claim as a self-governing country in the eyes of the international community. The PRC can point to UN Resolution 2758, which abrogated Taiwan from the OST and nullified any legal standing under both customary and treaty law upon the PRC’s accession to the OST. The PRC could point to this as proof Taiwan has no legal standing to assert jurisdiction and control of the satellites in question. This would serve to further erode Taiwan’s claim to autonomy and enhances the PRC’s own legal claim to Taiwan via UN Resolution 2758.[34]

Scenario 2

The second scenario relates to space control leading up to an invasion of Taiwan.[35] Access to space assets for communications, Internet, and remote sensing, including the FORMOSAT-8 series of satellites, will be vital for Taiwan to defend against an offensive action by the PRC. The PRC could utilize offensive space control via its substantial counterspace capabilities to degrade Taiwan’s space capabilities as a prelude to, and in the course of, direct military action. The PRC could vindicate its actions against these satellites pointing out that there is no registered launching State and the listing of Taiwan’s satellites in the Register of Space Objects as “Taiwan, Province of China” signifying these satellites are not a sovereign asset of Taiwan. Even though the PRC has not registered itself as the “launching State,” the PRC could assert UN Resolution 2758 would be controlling. The PRC could use this to blunt any criticism and argue it is influencing its own space assets and not interfering with the assets of a sovereign State consistent with international law.[36]

Scenario 3

The third scenario is ancillary to Scenario 2. The PRC could use this lawfare weakness to test for vulnerabilities in Taiwan’s space assets, including the FORMOSAT-8 series of satellites while claiming it remains compliant with international law. The PRC could use non-kinetic means to interfere with Taiwan’s space assets through cyberattacks, radiofrequency jamming, and dazzling. It could also utilize its rendezvous and proximity assets to make close orbital passes of Taiwan’s space assets or park within the vicinity. Any charges that the PRC was interfering with these assets could be rebuffed by Beijing pointing to the listing “Taiwan, Province of China” and the lack of a registered launching State in the Register of Space Objects to legitimize its actions as activities involving space assets under its jurisdiction and control consistent with international law and Resolution 2758 regardless of whether the PRC has registered these satellites as the launching State.[37]

Scenario 4

The fourth scenario is another potential avenue for the PRC to exploit this lawfare weakness through physical appropriation of Taiwan’s satellites. The PRC could employ cyberwarfare to take over Taiwanese satellites for their own use or to use against Taiwan. Protests by Taiwan and the international community would be challenged as Beijing could point to UN Resolution 2758 and to the listing in the Register as “Taiwan, Province of China,” and assert these assets have been under the sovereign jurisdiction of the PRC all along. This would allow it to posture its actions are consistent with international law regardless of whether the PRC registered these satellites as the launching State.[38]

These scenarios or variations of them have yet to play out, but they do illustrate the lawfare threat to Taiwan’s satellites that are currently in orbit and future satellites launched for Taiwan because of their listing as “Taiwan, Province of China.” Particularly, Scenarios 2, 3, and 4 represent a conceivable danger to the FORMOSAT-8 series of satellites once they are launched.

The vulnerability these scenarios represent will continue to be viable so long as the Office of Outer Space Affairs continues to list satellites launched by or for Taiwan as “Taiwan, Province of China,” and unless and until the PRC takes the step to register these satellites, they will continue to be in legal limbo. Yet, the lawfare trap Taiwan’s satellites operate within presents an opportunity for the US to use precedent from a Reagan-era policy to intervene and pull future Taiwanese satellites under its legal protection.

Operation Earnest Will

Operation Earnest Will was an extension of the Reagan Administration’s Cold War strategy.[39] In the fall of 1986, the Kuwait government approached both the US and the Soviet Union seeking protection for its tankers in the Persian Gulf amid hostilities between the Islamic Republic of Iran and Iraq. The Soviet Union, which had full diplomatic relations with Kuwait, responded to the request offering to reflag Kuwaiti tankers and receiving protection from the Soviet Navy with little more than raising the Soviet flag on the tankers.[41]

| The question is whether a variation on the strategy employed in Operation Earnest Will can be applied to the situation Taiwan finds with it satellites, and what benefit will accrue to the US in terms of great power competition in supporting such a solution? |

After debate by the National Security Council, the NSC and the Department of Defense agreed with the proposal to reflag Kuwait tankers, but the State Department objected. President Reagan concurred with NSC and the Department of Defense.[42] On March 17, 1987, then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral William J. Crowe, delivered a formal offer to the Kuwait’s emir, Sheikh Jabir al-Ahmad al-Sabah, for the US to provide naval escort to tankers belonging to the Kuwait Oil Tanker Company (KOTC).[43] The operation was to be done “by the book,” which required the creation of a shell company based in the US to transfer ownership of the tankers from the KOTC. The transfer would allow the tankers to be flagged by the US.

Attorneys for the KOTC facilitated this through the creation of Chesapeake Shipping Inc., which was incorporated in Dover, Delaware. Chesapeake Shipping, Inc. was a dummy corporation that had no employees. Its “offices” consisted of a mail drop at another company that specialized in dummy corporations, and controlling assets like the tankers, which were valued at approximately $350 million.[44] The first convoy under Operation Earnest Will began on July 22, 1987. The convoys continued until December 1989.

While the merits of re-flagging and escorting may be debated, at its heart Earnest Will was about great power competition and Cold War strategy. As observed by Andrew Marvin:

“EARNEST WILL was classic offensive realist offshore balancing. The United States kept the Soviet Union and Iran out, and Kuwait and Saudi Arabia in, while avoiding a permanent large garrison in the Gulf (its base in Bahrain was tiny). Reagan’s desire to confront perceived Soviet expansion more aggressively does much to explain the foreign policy decision to engage in EARNEST WILL. Its explanatory power stands in contrast to the proximate reason for Kuwait’s predicament. Protection of oil flows…played little strategic role in EARNEST WILL, despite the strategic proclamations of the Carter Doctrine and the administration’s communication efforts to remind Congress of its importance to the U.S. economy.”[45]

Operation Earnest Will was a lawfare operation in the maritime domain even though the term had not yet been created or defined.[46] The question is whether a variation on the strategy employed in Operation Earnest Will can be applied to the situation Taiwan finds with it satellites, and what benefit will accrue to the US in terms of great power competition in supporting such a solution?

References

- Even though the PRC was recognized as a Founding Member of the UN, it did not participate in the negotiation of the OST, nor did it become a party when it became open for signature on April 24, 1967. It eventually acceded to the OST on December 30, 1983. Regardless, the PRC’s space activities prior to accession were bound by customary international law through the Declaration of Legal Principles Governing the Exploration and Use of Outer Space

- UN: Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, China, Declarations, December 30, 1983.

- UN: Declaration to the United States: Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, China, December 30, 1983.

- UN: Declaration to the United Kingdom: Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, China, January 10, 1984.

- UN: Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, October 10, 1967, art. viii, 18 UST 2410.

- Michael Listner, Law as Force in Hybrid Warfare, Irregular Warfare Initiative, October 5, 2023.

- Xu Sanfie, Why did hybrid warfare theory come about?, China Military Forum, August 5, 2021..

- Professor Stephan Halper, China: The Three Warfares, For Andy Marshall, Director, Office of Net Assessment, Office of the Secretary of Defense, p.11, May 2013..

- Halper, 11.

- Halper, 11.

- Halper, 27.

- Office of the Secretary of Defense. Annual Report to Congress – Military and Security Developments involving the PRC 2011, 26.

- Carl Von Clausewitz, On War, 90, (Michael Howard & Peter Paret, ed, and trans.) (1993).

- Orde F. Kittre, Lawfare, Law as a Weapon of War, pp. 4-5, Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Maj. General Charles J Dunlap (ret), 2001, “Law and Military Interventions: Preserving Humanitarian Values in 21st Conflicts”, paper presented to Humanitarian Challenges in Military Intervention Conference, Carr Center for Human Rights Policy, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Washington, D.C, November 29, 2001..

- Carl von Clausewitz [edited, translated and introduced by Michael Howard and Peter Paret], On War, p.90, Everyman’ Library, 1993.

- Jill Goldenziel., Law as a Battlefield: The U.S., China, and Global Escalation of Lawfare (January 25, 2020). 106 Cornell Law Review 1085, 1097

- The definition of “lawfare” asserted by the author covers not only use of law in the international arena but also has application in the domestic setting using domestic laws, regulations and institutions to achieve political ends in the domestic arena.

- Clausewitz, 83.

- UN: Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, art. I(a), November 12, 1974, 1023 U.N.T.S. 15.

- Michael Listner, The Paradox of Article IX and National Security Space Activities, Air University AETHER, 28-33, January 12, 2023.

- UN: Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, October 10, 1967, art. viii, 18 UST 2410.

- UN Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, art. iii, November 12, 1974, 1023 U.N.T.S. 15.

- There is no evidence Taiwan has established an Article II(1) registry. Even if it has an Article II(1) registry, it would not be recognized in the international community or the UN except possibly the U.S. As will be discussed later, through the Taiwan Relations Act U.S. law would still be treat Taiwan as a State. Still, UN Resolution 2758 ensures there would be no international recognition of sovereignty for satellites registered nationally by Taiwan.

- UN Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, art. iv(1)(a), November 12, 1974, 1023 U.N.T.S. 15.

- UN Resolution 2758, Restoration of the lawful rights of the People's Republic of China in the United Nations, 1976th plenary meeting, October 25, 1971. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/192054.

- Two satellites launched for Taiwan have decayed: NUTSAT (1998-067UR), and ROCSAT 1 (1999-002A).

- Compiled from UN Online Index of Objects Launched Into Outer Space, UN Office of Outer Space Affairs using “Taiwan” as a search term. Note this chart does not include IRIS-F2 and IRIS-F3, which were launched on January 14, 2025.

- Lin Chia-nan, Taiwanese satellites registered at the UN as Chinese, Taipei Times, March 20, 2021.

- Even if Taiwan had legal standing to list or register its satellites, it would be counter-productive to its claim of autonomy from the PRC to admit Taiwan is “Taiwan, Province of China.”

- Lin Chia-nan, Taiwanese satellites registered at the UN as Chinese, Taipei Times, March 20, 2021.

- UN Resolution 2758, Restoration of the lawful rights of the People's Republic of China in the United Nations, 1976th plenary meeting, October 25, 1971.

- UN: Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, October 10, 1967, art. viii, 18 UST 2410.

- Guermantes Lailari, Michael J. Listner, Lawfare, Outer Space, Cyber Warfare, and ROC Vulnerabilities, Global Taiwan Institute, May 18, 2022.

- “Space control in geopolitical terms is the capability of a nation to maintain freedom of action in outer space and to deny the same to an adversary should national interests dictate.” Dana J Johnson, Trends in Space Control Capabilities and Ballistic Missile Threats: Implications for ASAT Arms Control, p. 1, March 1990.

- Guermantes Lailari, Michael J. Listner, Lawfare, Outer Space, Cyber Warfare, and ROC Vulnerabilities, Global Taiwan Institute, May 18, 2022.

- Id.

- Id.

- Andrew R. Marvin “Operation Earnest Will—The U.S. Foreign Policy behind U.S. Naval Operations in the Persian Gulf 1987–89; A Curious Case,” Naval War College Review: Vol. 73: No. 2 , Article 8, p.2. (2020).

- Marvin, Operation Earnest Will, 8.

- Marvin, 9.

- Marvin, 11.

- Marvin, 11.

- Marvin, 11.

- Marvin, 17.

- Maj. General Charles J Dunlap (ret), 2001, “Law and Military Interventions: Preserving Humanitarian Values in 21st Conflicts”, paper presented to Humanitarian Challenges in Military Intervention Conference, Carr Center for Human Rights Policy, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Washington, D.C, November 29, 2001..

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.