Taiwan’s satellites: A lawfare vulnerability and an option to cure and enhance deterrence against the PRC (part 3)by Michael J. Listner

|

| Freeing Taiwan’s satellites from the lawfare snare created by its legal status is not a quick fix and requires an audacious political strategy and the willingness by the US to engage in lawfare. |

Even though the US interpretation of Article VIII of the Outer Space Treaty (OST) asserts sovereignty over objects launched into space, the concept of “flagging” in the maritime legal domain is not identical or appropriate for objects launched into space. Still, the US can use Article VIII of the OST and the Registration Convention to execute a lawfare operation that would assert sovereignty over satellites launched for Taiwan and close the lawfare gap created with listing of Taiwan’s satellites as “for Taiwan, Province of China” by the UN’s Office of Outer Space Affairs and prevent the PRC from claiming jurisdiction and control over the same. Key to this is for the US to assert itself as the “launching State” for satellites currently in orbit and future satellites launched for Taiwan by the US. As a non-State, Taiwan cannot be the “launching State” even if it had an indigenous launch capability, and Resolution 2758 could be used to make the argument jurisdiction and control of Taiwan’s satellites are implicitly vested to the PRC.

One ancillary issue that must be disposed of beforehand is whether Resolution 2758 implicitly makes Taiwan a non-governmental under the jurisdiction of the PRC for purposes of Article VI and Article VIII of the OST.[1] If Resolution 2758 makes Taiwan a non-governmental under Article VI of the OST, satellites launched for or by Taiwan would be imputed to the PRC as a national activity.[2] Designating Taiwan as a non-governmental would require the PRC to authorize and continually supervise Taiwan’s activities as the language of Article VI prohibits strictly private activity that is unregulated.[3] Yet, there is no express or implied indication Taiwan sought the PRC’s approval for the launch of its satellites nor is there any indication the PRC sought to prevent Taiwan from having its satellites launched or otherwise regulate its outer space activities. Given this, arguing that Resolution 2758 makes Taiwan a non-governmental under Article VIII jurisdiction of the PRC falls short and does not justify the Office of Outer Space Affairs listing Taiwan’s satellites as “province of China” in the UN Register of Space Objects.

With the argument Resolution 2758 makes Taiwan a non-governmental disposed of, and the PRC has seemingly not asserted jurisdiction and control over the satellites in question both through its Article II(1) national registry or the Article III registry in the UN, the US has a legal opening to assert itself as the launching State per Article I(a)(ii). Two factors are critical for this to happen.

First, Taiwan must agree in principle to allow the US to assume jurisdiction and control of its satellites launched by the US as the launching State. At first blush, seeking Taiwan’s consent is an unnecessary step since Taiwan is a non-State with whom the US has no diplomatic relations, and the US can in theory assert itself as the launching State without seeking Taiwan’s consent.[4] However, skipping this step would be a political misstep that would reflect badly on US-Taiwan relations, and failing to seek Taiwan’s consent beforehand would technically violate Section 3303(a-b) of the Taiwan Relations Act.[5] It would also further delegitimize Taiwan’s claim to autonomy and enhance the PRC’s claim under Resolution 2758. Therefore, any effort by the US to place Taiwan’s satellites under its jurisdiction must be prefaced with the courtesy of a consultation if not a formality instead of the US exercising a legal right and effectively seizing these satellites unilaterally.

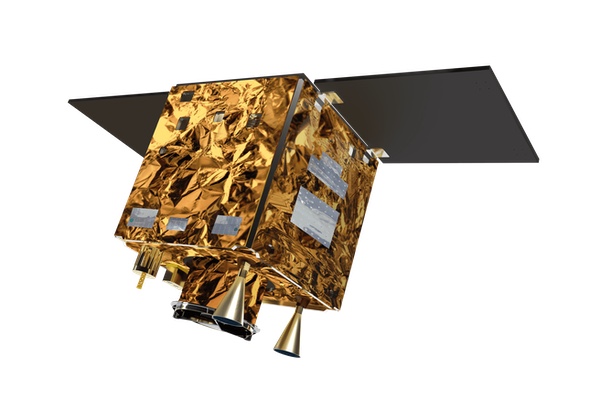

Convincing Taiwan to permit the US to extend jurisdiction and control as the launching State would not be unusual as the US has collaborated in outer space with Taiwan with more than 270 bilateral agreements and MOUs.[6] That collaboration includes the construction and launch of several satellites, including FORMOSAT-1, FORMOSAT-5, and the FORMOSAT-7 six-satellite constellation.[7] Indeed, the collaboration on these satellites, including launch, can be asserted as a US national activity under Article VI, which gives further legal support to the US registering as the launching State.[8]

The second factor is whether a US move to register Taiwan’s satellites would be legal. This is a two-fold question: The first concern is whether the PRC has registered Taiwan’s satellites in its Article II(1) registry.[9] If that is the case, the PRC could assert jurisdiction and control to preempt a US claim, but there is no evidence this has occurred nor is there any indication it intends to do so as indicated by the listing of “for Taiwan, Province of China” in the Article III UN Register of Objects. Since the PRC has not taken this step, the US can assert its legal right under Article 1(a)(ii) as the launching State and register satellites launched for Taiwan in its Article II(1) national registry maintained by the Department of State.[10] Subsequent to registration, the US can file for registration in the Article III UN Register of Space Objects displacing the listing of these satellites “for Taiwan, Province of China” and registering them under the jurisdiction of the US.

But, would US domestic law and policy surrounding Taiwan permit this action? The answer lies in both the legal nature of the Registration Convention under US law and the Taiwan Relations Act.

Under the US Constitution, a ratified treaty has the same standing as federal law, which makes the Registration Convention and its provisions the equivalent of a federal statute, including the definition of “launching State” in Article I(a) and the legal duty to register a space object in Article II(1) and Article III.[11] With the Registration Convention having the standing of federal law, the Taiwan Relations Act becomes the connective tissue for the US to assert its right as the launching State for Taiwan’s satellites and its duty to register the same through Section 3303(a-b). The Registration Convention’s status as federal law applied through the Taiwan Relations Act also allows the US to hold out Taiwan as if it was legally obligated both under Article VIII of the OST and under the Registration Convention. This means Taiwan is considered a launching State along with the US under Article I(b)(ii) of the Registration Convention for purposes of the US launching satellites for Taiwan and, in effect, invalidates the PRC’s declaration quashing Taiwan’s standing in international space law from the perspective of US federal law.[12]

Accordingly, the US can then negotiate with Taiwan through the American Taiwan Institute pursuant to Article II(2) of the Registration Convention and gain Taiwan’s consent for the US to assert itself as the launching State for FORMOSAT-1, FORMOSAT-5, and the FORMOSAT-7 constellation of satellites as well as any future satellites launched for Taiwan by the US, including FORMOSAT-8.[13]

The legal effect is to use both the Registration Convention and the Taiwan Relations Act to register these satellites to the US as the launching State in both the US Article II(1) national registry and the Article III Register of Space Objects at the UN, and pull Taiwan’s satellites from the legal limbo of being listed as “for Taiwan, Province of China” and placed under the jurisdiction and control and hence sovereign authority of the US per Article VIII of OST.[14] The one hitch is once the US becomes the launching State under the Registration Convention, it will also assume liability for Taiwan’s satellites per the OST and the Liability Convention, which it would shoulder in perpetuity.[15]

Implementing a lawfare strategy like this would be a bold political move and controversial not just for the PRC but domestically as well. Whether the National Security Council, the Department of Defense, and the State Department would support such an audacious lawfare operation is uncertain, much less the White House. Aside from that is its long-term political viability.

While an executive order from the President can implement such a policy, it is uncertain whether the political ebb and flow of executive politics and foreign policy would find support for such a move from administration to administration. A long-term solution would be for Congress to pass legislation that makes the policy federal law. One approach to achieve this is to amend Title 22, Chapter 48a “Taiwan Enhanced Resilience” to codify the policy of registering Taiwan’s satellites as federal law as opposed to executive foreign policy.

An amendment to Title 22, Chapter 48a might look like this:

“§ 3357(c) - Satellites launched for Taiwan. (1) Notwithstanding United Nations Resolution 2758 and considering the Taiwan Relations Act, the United States with the consent of the Taiwanese government shall under international treaties and conventions the United States is party to be considered to have sovereign authority and having jurisdiction and control of and/or the “launching State” of satellites launched for Taiwan by the United States.

(2) The launching of a satellite for Taiwan will be considered a national activity of the United States. The United States will assume sovereignty of and claim all rights and assume all obligations under international law, including jurisdiction and control, ownership and liability for satellites launched for Taiwan.

(3) The Department of State shall register satellites launched for Taiwan in the U.S. registry of space objects not later than seven (7) days after the launch of the satellite.

(4) The Department of State shall file for registration as the “launching State” with the UN Office of Outer Space Affairs within a reasonable time after registering the satellites in the U.S. register.

(5) Any actions or interference by the People’s Republic of China or any other foreign nation with or against satellites launched for Taiwan and registered by the United States will be considered a hostile act against the United States and incongruent to the PRC’s stated goal of the peaceful reunification of Taiwan.

(6) The President and the Executive Branch shall encourage its allies who also launch satellites for Taiwan or permit the launch of Taiwan’s satellites from its territory to similarly register Taiwan’s satellites in their national register and file as the “launching State” under international law.

This is admittedly a first pass at a legislative solution, but it represents a means to entrench this policy in federal law and ensure a US policy towards Taiwan’s satellites would survive the ebb and flow of foreign policy prescribed by successive presidential administrations. This presents an opportunity for both the current administration and the 119th Congress should either or both choose to act.

How will the PRC respond?

How would the PRC respond politically if the US successfully asserted jurisdiction over not only the satellites it has launched for Taiwan but also future satellites like the FORMOSAT-8 series, which have national security value for Taiwan? The PRC would certainly lobby voraciously against a move by the US to register Taiwan’s satellites even though under the letter of international law the US has the legal right to do so. Certainly, if there is a PRC lawfare operation within the Office of Outer Space Affairs or in the UN itself, it might try to stymie a US effort to register Taiwan’s satellites. Tensions between Washington and Beijing would certainly be heightened, but it will also test the applicability and breadth of and dilute the effect of UN Resolution 2758 as customary international law.

| This would end the legal ambiguity over the standing of Taiwan’s satellites, create a bright line for the PRC to consider before interfering with Taiwan’s satellites, and strengthen Taiwan’s claim to autonomy on the geopolitical stage |

Regardless of whether the listing of Taiwan’s satellites as “for Taiwan, Province of China” is the result of a PRC-sponsored lawfare action or an administrative practice the PRC could assert the listing can be inferred as an acknowledgement of the PRC’s jurisdiction and control over the satellites through UN Resolution 2758 and hence declare customary international law controls the ownership of the satellites. However, as discussed in Part 1, the presumption of customary international law for a declaratory resolution like UN Resolution 2758 can be overcome by evidence of a significant state practice or principle of international law that is contrary to the principle within the declaration.[16]

The U.S. can counter the PRC’s assertion of UN Resolution 2758 stating that Article 1(a)(ii) of the Registration Convention as a treaty ratified by the US and acceded to by the PRC supersedes the customary international law claim of Resolution 2758 for the satellites in question.[17] Specifically, the US can assert that Article 1(a)(ii) of the Registration Convention conflicts with and supersedes the PRC’s assertion of customary international law under UN Resolution 2758.[18] In other words, the PRC’s claim under customary international law conflicts with and is subordinate to the US claim under Article 1(a)(ii) of the Registration Convention, which means the US claim must prevail.

The PRC could attempt to assert itself as the launching State and register Taiwan’s satellites in its Article II(1) national registry to preempt a US claim of sovereignty and registration in the Article(III) UN Register of Space Objects? If both States assert themselves as the launching State, then Article III(2) controls where the PRC and the US would have to come to agreement who can assert jurisdiction as the launching state. The PRC would likely be unwilling to negotiate and brandish customary international law through UN Resolution 2758 to assert that the satellites are under their jurisdiction and control, although as discussed above its obligations under the Registration Convention would preempt the declaratory resolution’s effect as customary international law.

Whether the Office of Outer Space Affairs would honor a US registration or reject it in favor of a PRC filing even if the US filing was made first is uncertain, although there is no precept that filing first in time is a determinative factor. Still, if the Office of Outer Space Affairs supports the PRC’s claim, it would have to explain its legal rationale for rejecting the US claim, why the office lists Taiwan’s satellites as “for Taiwan, Province of China”, whether it believes Resolution 2758 is controlling, and. if so, whether a declaratory resolution supersedes a legally binding treaty.

Aside from the legal aspects, a challenge by the PRC over jurisdiction and ownership of Taiwan’s satellites would be a significant test of US policy towards Taiwan. If the US counters a challenge by the PRC, it will likely prevail under international law as discussed above. On the one hand, if the US acquiesces to the PRC’s claim without a challenge, it will raise questions about US policy towards Taiwan’s autonomy. This in turn would raise concern in Taipei as to the commitment of US policy towards its autonomy, signal a shift in policy to the greater geopolitical community, implicitly bolster the PRC’s assertion of Resolution 2758 and its claim to Taiwan. The consequence of this scenario is a US claim of sovereignty as the launching State for satellites it has launched and will launch for Taiwan is consistent with and critical to supporting US policy towards Taiwan in the geopolitical sphere both in terms of optics and deterrence.

The PRC would suffer political humiliation but one it might take in stride along with the loss of a potential lawfare advantage in its calculus to annex Taiwan. Irrespective of the diplomatic and political blowback with the PRC, if the US successfully registers itself as the launching State of Taiwan’s satellites, it will preempt a bureaucratic practice or lawfare operation in the Office of Outer Space Affairs and close a lawfare loophole for several of Taiwan’s satellites. This would end the legal ambiguity over the standing of Taiwan’s satellites, create a bright line for the PRC to consider before interfering with Taiwan’s satellites, and strengthen Taiwan’s claim to autonomy on the geopolitical stage. It would also show to the PRC the US is willing to engage with lawfare and hybrid warfare in great power competition and as a result create a deterrent effect to the former’s use of the Three Warfares on the world’s stage.

Other aspects to consider

Another aspect of this discussion is Taiwan launching its own satellites. A Taiwanese non-governmental entity is developing a ballistic launcher under Australia’s Article VI authorization for non-governmental space activities.[19] The Taiwanese company tiSPACE was granted a license by the Australian government to launch its Hapith I, which is a 10-meter, two-stage, suborbital rocket, from the Whalers Way Orbital Launch Complex.[20] Presuming this is not a disguised development program to create an intermediate to long-range ballistic missile capability for Taiwan, this effort may lead to a domestic launch capability for Taiwan.

Launching satellites from Australia would not avoid the administrative practice or lawfare operation within the Office of Outer Space Affairs that would list them as “for Taiwan, Province of China” as it has with Taiwan’s other satellites. The question is would Australia be prompted by a US lawfare strategy and adopt a similar stance and assert itself as the launching State and register Taiwanese satellites in its Article II(1) national register and the Article III UN Register of Space Objects?[21] This would be determined in no small part by Australia’s stance on Taiwan and its relations with the PRC. Australia’s stance on Taiwan is stated by Australia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and is opaque.[22]

| Even if the US asserts sovereignty over these satellites, it does not mean Taiwan’s satellites would be safe from interference leading up to and during a conflict with the PRC. |

Unlike the US, Australia does not have legislation codifying its Taiwan policy, and Australia appears to be walking an even narrower tightrope than the US when it comes to Taiwan and relations with the PRC. This likely has much to do with its regional proximity to the PRC, not to mention the trade relations both States engage in. While the Australian government appears to be allowing Taiwan to develop a launch capability under its jurisdiction, it is uncertain whether it would seek to stir Beijing’s ire by legitimizing Taiwan’s autonomy through registering satellites launched from Australia both in its Article II(1) national registry and the Article III UN Register of Space Objects. Nonetheless, attitudes towards the PRC appear to be evolving with Australia as a key member of the AUKUS security agreement, which recognizes the growing threat in the region. This reality might open Australia to take the step and act as the launching State for Taiwanese satellites launched from its territory if the US acts first and sets the precedent.[23] Indeed, another State taking this action would further Taiwan’s legitimacy but also potentially create a state practice that can start the path to become customary international law.

Overall, the decision for the US or its allies to employ lawfare and take this action is a political decision that must consider state interests and the potential geopolitical pitfalls. Regardless of state interest, the US might be compelled under federal law to consider such a lawfare strategy. The Taiwan Enhanced Resilience in Title 22, Chapter 48a of the United States Code might require the US to explore the matter with Taiwan.[24] Section 3351 requires an annual report to Congress that in part addresses:

“…any other defense capabilities that the United States determines, including jointly with Taiwan, are crucial to the defense of Taiwan, consistent with the joint consultative mechanism with Taiwan created pursuant to section 3355 of this title…”[25]

Arguably, securing Taiwan’s satellites under the jurisdiction and control and hence sovereignty of the US as the launching State would be crucial to Taiwan’s defense and in the state interest of the US to implement and to comply with 22 U.S.C. § 3351.

Even if the US asserts sovereignty over these satellites, it does not mean Taiwan’s satellites would be safe from interference leading up to and during a conflict with the PRC. The reality is these satellites, along with other US satellites, would be exposed to and could be targeted by the PLA’s counterspace capabilities as a precursor to or after hostilities break out with the US. Still, asserting sovereignty over Taiwan’s satellites would deprive the PRC the use of international law as a shield to interfere with these satellites in any of the four scenarios discussed or otherwise assert its jurisdiction and control as a legal and political defense.

There is the consideration a US policy posturing this action or even the suggestion of the idea in this article might prompt the PRC to take action preemptively and attempt to register the satellites launched for Taiwan currently in orbit in its Article II(1) national registry, including those launched by the US and then with the with the Article IV register in Office of Outer Space Affairs. This is not out of the question and a concern that must not be idly dismissed.[26] Nonetheless, if the PRC took such preemptive action asserting UN Resolution 2758, not only can it be challenged as discussed above, but it could be seen as a prelude to the PRC annexing Taiwan when it may not be politically feasible for Beijing to do so, which might in turn could create an international incident that would upset any timeline it has established to annex Taiwan.

One final thought before closing this section. Suppose the US does become the launching State for several of Taiwan’s satellites and asserts sovereignty over them and, later, the PRC annexes Taiwan either through force or peaceful reunification. Presume the satellites the US has asserted sovereignty over survive either through their natural lives or escape the PRC’s counterspace capabilities. What happens to those satellites? Would the PRC demand the US relinquish sovereign control or would the PRC just chock up the loss of the satellites as part of the cost of annexing Taiwan? If the former occurs, there are several hurdles both diplomatically and legally that would have to be overcome, including issues of liability. These troubles are beyond the scope of this article, but it is sensible to acknowledge that gaining sovereignty over Taiwan’s satellites could open after-effects with the shifting of geopolitical winds.

Could this lawfare weakness be exploited?

Interdicting the PRC from exploiting the lawfare loophole presented in this article presumes the US acknowledges the inherent lawfare vulnerability to Taiwan’s satellites to begin with. Western geopolitical strategy is based on chess where the object is political attrition to eliminate the king. Conversely, the PRC’s strategy is based on Go, where the object is to gradually gain territory or deny the same to an adversary. It is the dichotomy of these two geopolitical approaches where the efficacy of lawfare and the Three Warfares is crucial and where US distrust of the same puts it at a strategic disadvantage.

The lawfare vulnerability of Taiwan’s satellites is reflective of the PRC’s Go strategy, and the U.S. must set aside skepticism and recognize the possibility that such a vulnerability exists, but more critically it must set aside its unwillingness to employ lawfare to address it.[27] Only then can it move to close the lawfare loophole before the PRC files to register Taiwan’s satellites in its Article II(1) national registry and the Article IV register with the Office of Outer Space Affairs. Knowingly allowing this lawfare loophole to exist and potentially be exploited will not only further legitimize the PRC’s claim to Taiwan but also prematurely expose national security space assets that are critical to Taiwan’s defense. It will also encourage the PRC to continue to implement its Three Warfares strategy without fear of challenge and further exploit Resolution 2758 for other of its state interests in other domains.

Consequently, the question is begged whether such a lawfare operation in the Office of Outer Space Affairs exists and would the PRC exploit the lawfare vulnerability it created? The PRC’s activities, including a recent lawfare operation against the Starlink satellite system in the UN, suggests the answer to that question is affirmative.

The PRC employed the Three Warfares with a lawfare operation against the Starlink non-geostationary satellite system in the UN using Article V of the OST when the delegation from the PRC filed a communiqué directly to the UN Secretary General on December 6, 2021. The communiqué alleged Starlink satellites nearly collided twice with the PRC space station in 2020.[28] The PRC took the opportunity in the communiqué to “remind” the US of its responsibilities over non-governmentals performing space activities.

The PRC’s objective of this operation was four-fold: engineer Article V into a lawfare tool for future use in the UN, discredit and sequester the utility of Starlink and non-governmental space activities, discredit the standing and authority of the US to create standards of behavior and norms for outer space activities and test the US response to the use of lawfare and Three Warfare tactics directed to the outer space domain.[29]

This lawfare action suggests that the PRC is actively applying lawfare to the outer space domain and makes the case for a lawfare operation using the UN against Taiwan’s satellites a plausible scenario.

Concluding thoughts

The lawfare conundrum with the legal status of Taiwan’s satellites is part of the larger scope of great power competition between the U.S. and the PRC. This is borne out in a 2021 report from the Director of National Intelligence where it says:

“The United States and China will have the greatest influence on global dynamics, supporting competing visions of the international system and governance that reflect their core interests and ideologies. This rivalry will affect most domains, straining and in some cases reshaping existing alliances, international organizations, and the norms and rules that have underpinned the international order.”[30]

| Whether any of the scenarios discussed here materialize where Tawain’s satellites can be co-opted by a PRC lawfare operation remains to be seen, but it should not be idly rejected just because it clashes with Western strategic thinking. |

The issue of the legal status of Taiwan’s satellites is a small aspect of great power competition; however, the US and its allies should recognize the existence and use of lawfare in all domains, including outer space. The question of the legal status of Taiwan’s satellites and the potential of a lawfare operation within an institution of the UN to facilitate that legal status for the PRC’s political benefit and in furtherance of other of its national interests should not be ignored. Despite this, Western contemporary strategic thinking and distrust and distaste for lawfare may dismiss the potential threat discussed here and the legitimacy of lawfare, hybrid warfare and the Three Warfares in general and its application by the PRC in furtherance of great power competition.

Whether any of the scenarios discussed here materialize where Tawain’s satellites can be co-opted by a PRC lawfare operation remains to be seen, but it should not be idly rejected just because it clashes with Western strategic thinking and the misconception maintaining the rule of law would be tarnished by acknowledging and employing lawfare.[31] Indeed, as demonstrated in this article, lawfare has been and can be employed effectively by using the law in a manner that does not denigrate the law but enhances and clarifies it through state practice while meeting critical state interests.

The thesis proposed in this article provides both the current Administration and the 119th Congress an opportunity to not only further its policy towards Taiwan, but also to take a substantial first step to embrace the concept of hybrid warfare, including lawfare, not as an academic exercise but as a government-wide strategy. Whether that strategy is non-classified or otherwise is left to the assessment of those with that authority; however, that strategy must direct government agencies, including the Department of State, Department of Defense, and the intelligence community, to move outside their comfort zones of preconceived notions and ideology and give them the directive and authority to employ lawfare beyond academic exercises and wargaming.[32]

That said, the potential lawfare vulnerability inherent to Taiwan’s satellites should be a bellwether to the US to consider setting aside its institutional bias and distrust for lawfare and hybrid warfare in general. Only then can the U.S. address the realpolitik of the PRC’s activities employing the Three Warfares to exploit vulnerabilities to achieve its political aims and state interests without fighting and challenging US dominance on the world stage.[33]

References

- This issue was raised by a peer reviewer prior to the article being accepted. The author includes it here as it is a worthy question to consider and dispose of.

- Bin Cheng, Article VI of the 1967 Space Treaty Revisited: “International Responsibility”, “National Activities”, and the Appropriate State, Journal of Space Law, 14, Volume 26, Number 1, 1998.

- Paul G. Dembling and Daniel M. Arons, “The Evolution of the Outer Space Treaty,” Journal of Air Law and Commerce 33 (1967), 437.

- As the U.S. has no diplomatic relations with Taiwan, the U.S. would have to make the overture through the American Taiwan Institute. Taiwan Relations Act, 22 U.S.C. § 3305.

- Again, this was brought up by a peer reviewer, i.e., if the presumption is Taiwan has no legal claim to these satellites, the U.S. should be able to just step in and assert jurisdiction as the launching State.

- Erik M. Jacobs, Taiwan-US Science and Technology Cooperation Continues with Satellite Program, Global Taiwan Center, April 20, 2022.

- Id.

- Another consideration is whether the Taiwan has its own “national registry” and whether it has listed its satellites within. Taiwan as a non-State is not a party to the Registration Convention nor does it appear Taiwan asserts the precepts of the Registration as customary international law. Regardless, Taiwan’s registration in its “national registry” would not be recognized as it cannot assert international law customary or not. Still, under the Taiwan Relations Act, the U.S. would be obligated to recognize Taiwan’s national registry and would have to negotiate with Taiwan to transfer jurisdiction of those satellites to the U.S. as the launching State.

- The PRC established its registry in 2001. UN: Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, Information furnished in conformity with the Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, Note verbale dated 8 June 2005 from the Permanent Mission of China to the United Nations (Vienna) addressed to the Secretary-General, ST /SG/SER.E/INF.17, June 21, 2005. UN: Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, art. II(1) November 12, 1974, 1023 U.N.T.S. 15.

- UN: Information furnished in conformity with the Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, ST/SG/SER.SE/INF.3, February 17, 1977. UN: Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, art. II(1) November 12, 1974, 1023 U.N.T.S. 15.

- “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.” U.S. CONST. art. 6.

- UN: Declaration to the United States: Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, China, December 30, 1983.

- UN: Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, art. iii and iv, November 12, 1974, 1023 U.N.T.S. 15.

- UN: Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, October 10, 1967, art. viii, 18 UST 2410.

- At this point, the definition of “launching State” in Article 1(c) of the Liability Convention becomes relevant. UN: Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, October 10, 1967, art. vii, 18 UST 2410. UN: Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects, art. I(a)(ii), art. II and art III, Nov. 29, 1971, 961 U.N.T.S. 187

- Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Directorate, Legal Effect of United Nations Resolutions Under International and Domestic Law, 4, LL File No. 2015-012099 LRA-D-PUB-000467 (2015).

- The Registration Convention was acceded to by the PRC on September 17, 1981, which is two years before it acceded to the Outer Space Treaty.

- Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Directorate, Legal Effect of United Nations Resolutions Under International and Domestic Law, 4, LL File No. 2015-012099 LRA-D-PUB-000467 (2015).

- Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, October 10, 1967, art. vi, 18 UST 2410.

- The Hon. Dan Tehan MP, The Hon. Christian Porter MP, Joint Media Release: Commercial rocket launch permit granted for South Australia, August 21, 2023.

- Convention on Registration of Objects Launched into Outer Space, art. i(a), November 12, 1974, 1023 U.N.T.S. 15.

- Australia: Department of Foreign Affairs and Ministry, Australia-Taiwan Relationship: Overview.

- This might require the Parliament of the Commonwealth to create a legal mechanism to do so.

- Taiwan Enhanced Resilience was passed as part of the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, Pub. L. No. 117-263, § 1263, 136 Stat. 2395.

- Taiwan Enhanced Resilience 22 U.S.C. § 3351(f)(2)(xiv).

- This concern has been considered by the author, and in fact was mentioned by one of the two peer reviewers who evaluated this article for publication.

- At the Fourth USSPACECOM Legal Conference, a representative from the Office of Secretary of Defense stated unequivocally during a panel discussion on lawfare that the Department of Defense would not be doing lawfare. This position reflected reluctance and even fear of the term lawfare and the idea of operationalizing lawfare. Air Force Academy: Law and Technology Warfare Research Cell, USSPACECOM Legal Conf 2024 Day 1 Panel 3, Strategic Competition and the Rise of Space Lawfare.

- Information furnished in conformity with the Treaty on Principals Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Note verbale dated 3 December 2021 from the Permanent Mission of China to the United Nations (Vienna) addressed to the Secretary-General, A/AC.105/1262, 6 December 2021.

- Michael J. Listner, China, Article V, Starlink, and hybrid warfare: An assessment of a lawfare operation, The Space Review, September 11, 2023.

- Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Global Trends 2040, p. 90 (2021).

- Michael Listner, Law as Force in Hybrid Warfare, Irregular Warfare Initiative, October 5, 2023.

- Congress has mandated the created of an “Irregular Warfare Center” to explore these concepts, yet the Center’s activities have focused substantially on academic theory and fellowships and less on practical application. Indeed, two Senators have expressed their displeasure at the lack of motivation on implementing the mission of the Center.

- “Sun Tzu, James Clavell (edited and with foreword), The Art of War, p. 15, Delacorte Press, 1983.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.