Superman and the Skylab rescueby Dwayne Day

|

Skylab was launched in 1973 and suffered a mishap during launch, requiring the Skylab 2 crew to repair it. During the Skylab 3 mission, a problem with the thrusters on the Apollo spacecraft caused NASA to begin implementing its rescue plan. (credit: NASA) |

SL-R

NASA began working on its Skylab rescue planning in early 1972, producing an initial set of requirements by May. They were updated again in November to include readiness response times and provide data missing from the initial document. The plans were updated again in May 1973, right before the first Skylab launch, and then a last time in August 1973, before the last launch—but after a major scare during the second crewed mission. Both NASA’s Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, which managed astronaut missions, and NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, which designed Skylab, jointly produced a 40-page report on the proposed rescue plan.

| Three crewed missions were planned (Skylab 2, 3, and 4) and the SL-R plan during these missions was for the next vehicle in-line to serve as the rescue vehicle. |

The rescue CSM would be flown by two astronauts and equipped with special seats for accommodating three extra astronauts, for a total of five. They would be cramped inside the spacecraft, but they could still return home. A key focus of the planning was salvaging as much mission data as possible.

The mission, which NASA designated SL-R, was a contingency mission designed to safely return the crew should the docked Command and Service Module “be rendered unusable for a safe return.” Three crewed missions were planned (Skylab 2, 3, and 4) and the SL-R plan during these missions was for the next vehicle in-line to serve as the rescue vehicle. The program also had a backup CSM and Saturn IB in addition to the in-line vehicle.

The in-line and backup vehicles would continue in a normal state of readiness until a decision was made that the SL-R mission was required. At that time the rescue field modification kit would be installed in the in-line vehicle according to an accelerated schedule. A second kit would be installed in the backup during the planned test and checkout flow. The rescue CSM would be launched with two astronauts, rendezvous and dock with Skylab, and retrieve the Skylab crew, returning to Earth with five astronauts. But the goal of the mission was not simply saving the stranded astronauts, but making sure their mission was not in vain.

Skylab grew out of the Apollo Applications Program (AAP) to use Apollo hardware for non-lunar missions. Early AAP plans were unrealistic, and the program was dramatically scaled back as NASA's budget shrank.. (credit: NASA) |

Rescuing poop data

In addition to rescuing the crew, the mission would consider returning selected experiment payload data, performing a diagnosis of the CSM failure, and configuring the Skylab for revisit, provided those tasks did not compromise the primary mission. Most of the rescue planning document was devoted to what data to preserve and how to make tradeoffs about what to bring back to Earth.

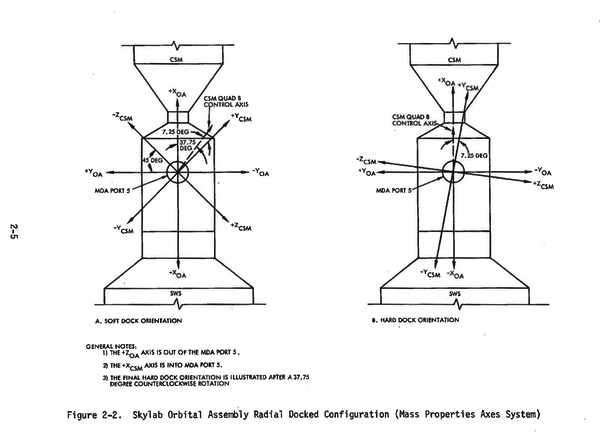

The timeline was to plan for a rescue mission capable of launching as early as mission days five, six, or seven. The mission should be able to accommodate options that included the disabled CSM jettisoned or still docked to Skylab. If the CSM was jettisoned, the rescue CSM would dock in the normal, axial, docking location at Skylab. If the disabled CSM was not jettisoned, the rescue CSM would have to dock at the radial position, 90 degrees perpendicular to the axial docking port. This would require special procedures to enable the best lighting position for docking. The maximum time that the rescue CSM would be docked to either port would be 40 hours, and total nominal mission duration would be limited to five days from launch to splashdown.

Illustration from the Skylab rescue plan detailing how the rescue astronauts might dock with the secondary docking port on the space station if the crippled original Apollo spacecraft was not jettisoned. (credit: NASA) |

At least one rescue crewman would be required to sleep in the rescue CSM during the docked phase if a sleep period was scheduled. Ballast (to compensate for the missing third astronaut during launch) would be transferred from the rescue CSM to Skylab prior to undocking.

Skylab was equipped with the Apollo Telescope Mount, which held multiple instruments for Earth and Sun observing. Many of these used film, and that film would have to be retrieved by extravehicular activity (EVA) prior to the docking of the rescue CSM. Not all of the film could be retrieved by the rescue CSM, so some would have to be stored on Skylab, hopefully for retrieval by a later mission.

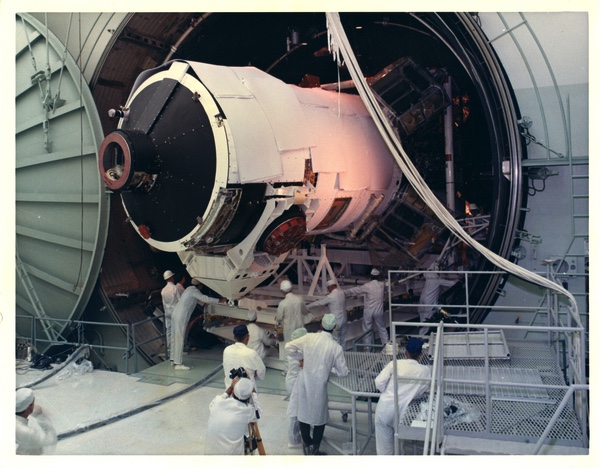

Everything about Skylab was big. Here the Multiple Docking Adapter is undergoing checkout and testing. The MDA had two docking ports for Apollo spacecraft, and was also the connection point for the Apollo Telescope Mount, which held multiple instruments. (credit: McDonnell Douglas via Michael Mackowski) |

The rescue plan established guidelines for return of experiment data, noting that reductions from a normal mission return would affect all experiments. The priority was to “select data to maximize scientific return with each experiment group rather than maximizing return of single experiments.” This would be based upon quantity and quality of data on previous missions, the present mission, data return of the present mission by alternate means such as telemetry, voice, and TV, and finally, expected return on any subsequent mission.

A major aspect of Skylab research was monitoring the health of the crew—much of which would be accomplished on the ground using samples collected from the astronauts in space. Therefore, the rescue mission allowed up to 127 pounds (57.6 kilograms) for the urine chiller and contents. Mass was also allocated for other medical samples, including fecal and vomitus samples, ATM film, and other film and tape. The rescue plan provided detailed instructions on what to return and how to make trade-offs in the different types of scientific data.

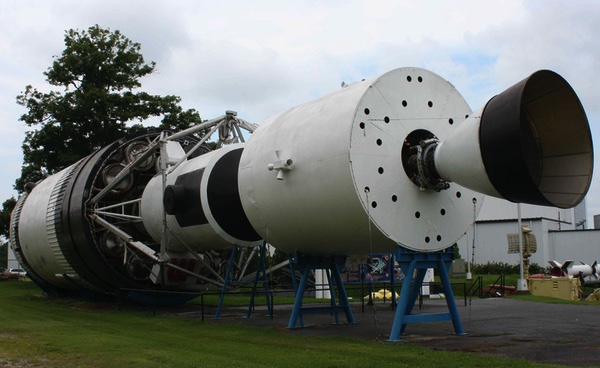

Skylab was based on the third stage of the Saturn V rocket and included a large payload shroud. The shroud was tested in Ohio. (credit: NASA) |

Rescue of a different kind

Skylab was launched May 14, 1973. During its flight through the atmosphere, the workshop’s meteoroid shield broke loose and ripped off one of its two main solar panels. Ground-based radars detected multiple pieces of debris coming off the station. Skylab entered orbit and jettisoned its large payload fairing as planned, but it was severely damaged. (See “Saving Skylab the top secret way,” The Space Review, May 22, 2023.)

| “We were so clever as the backup crew,” said Lind, “that we worked ourselves out of a flight!” |

After Skylab was launched in mid-May, Skylab 2, carrying astronauts Pete Conrad, Joseph Kerwin, and Paul Weitz was launched 11 days later on a mission to rescue and repair the damaged laboratory. It was a bold plan that worked. The Skylab 2 astronauts spent 28 days on the space station.

The Skylab program went on to great success. Skylab 3 was launched on July 28 on a 54-day mission. But not everything went smoothly, and the rescue scenario was almost put into action. While Alan Bean, Owen Garriott, and Jack Lousma were aboard the station during the Skylab 3 mission in August 1973, one of the on-orbit spacecraft’s quad thrusters failed. Soon a second quad thruster began to fail.

NASA began a rescue launch campaign. Astronauts Vance Brand and Don Lind had been selected as the rescue astronauts for both Skylab 2 and 3. They began preparing for the rescue mission. However, as they started training in the simulator, they determined that it was still possible to fly the Apollo spacecraft without the thrusters. “We were so clever as the backup crew,” said Lind, “that we worked ourselves out of a flight!”

“You really didn’t want to have to go rescue them,” he added. “You really wanted to bring them back safely with all their equipment.”

By August 10, NASA canceled the rescue mission after it became clear that the spacecraft could safely return the crew. For the final Skylab mission, Skylab 4, launched November 16 on an 84-day mission, NASA had a Saturn IB rocket with an Apollo spacecraft positioned on the launch pad on December 5. It remained there until the Skylab 4 crew successfully returned to Earth. The Saturn IB and Apollo were then returned to the Vehicle Assembly Building and later used for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project.

Skylab was based on the third stage of the Saturn V rocket and included a large payload shroud. The shroud was tested in Ohio. (credit: NASA) |

Postscript

Marooned posed a much tougher problem than NASA faced during Skylab 3—a CSM stranded in orbit, not attached to Skylab. But as the late, great John Charles wrote in 2019, that was a highly unlikely scenario, because there were multiple methods to retrieve an Apollo Command Module even in the very unlikely event that the main engine failed. (See “Saving Colonel Pruitt,” The Space Review, June 3, 2019.) NASA had prepared for almost every possible scenario.

In 1972, 16-year-old Tim Gagnon wrote to his senator asking him to arrange an invitation for Tim and his father to the launch of Apollo 17. He was surprised when he said yes. “During the visit to KSC, we attended the prelaunch briefings and one included the story of the patch,” Gagnon remembered over half a century later. “Sitting in the audience I decided that this is what I wanted to do.”

Tim Gagnon proposed this patch design for the Skylab Rescue mission in 1973. It was not needed or produced, but decades later he made a limited number of the patches. (credit: Tim Gagnon) |

“The next year I began writing to astronauts asking if I might help design their patch. The Skylab mission patches had all been done but in the summer an issue arose during the second crewed increment with the reaction control system on the Service Module,” Gagnon recalled. “When Vance Brand and Don Lind were announced as the Rescue crew, I submitted two designs for their patch.” One was an “official” design, and the other was a fun design showing Superman bringing the Command Module back to Earth. “I had in mind the Apollo 14 backup patch when I drew that one.”

.In 1973, Tim Gagnon also designed a “fun” patch for the Skylab Rescue mission. (credit: Tim Gagnon and Jorge Cartes) |

Gagnon later went on to design space mission patches for NASA. “Fast forward to 2017 and I meet Vance Brand and his wife Beverly at Spacefest in Tucson. I greet them and say, Sir, you have no reason to remember this but in 1973 I sent you patch designs for the Skylab Rescue mission.” Brand’s wife said, “I know exactly where they are and when we return home I’ll get our son to take them down from the attic.” In September 2017, Gagnon received the package with the drawings he had not seen in 44 years.

Gagnon licensed AB Emblem to make and sell them and they are available for sale.

Sources

Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center and George C. Marshall Space Flight Center, “Mission Requirements: Skylab Rescue Mission SL-R,” August 24, 1973. The rescue plan can be downloaded here.

Ben Evans, “Launch Minus Nine Days: The Space Rescue That Never Was.”

David J. Shayler, David. J., Space Rescue: Ensuring the Safety of Manned Spaceflight, Springer, 2009

NASA, History of Space Shuttle Rendezvous, JSC-63400, Revision 3, Mission Operations Directorate, Flight Dynamics Division, October 2011, chapter 5.

J. Muratore, “Space Rescue,” NASA, 2007.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.