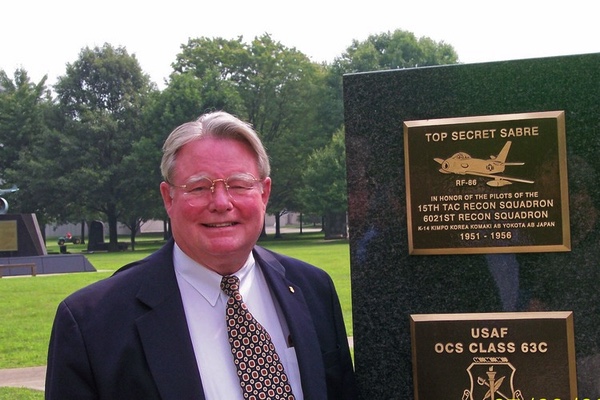

In memoriam: R. Cargill Hallby Dwayne Day

|

| Cargill believed in making early Cold War history public, and worked on doing what he could. That was an unusual attitude for a military historian. |

Cargill wrote Lunar Impact: The History of Project Ranger. That book was an important program history sponsored by NASA. The agency also sponsored a history of Lunar Orbiter, although sadly, not an official history of Surveyor. Lunar Impact detailed the turbulent early years of Ranger, and the management shakeup that took place as a result. Cargill was the winner of the first Robert Goddard Historical Essay Award.

In the 1970s, Cargill began writing histories for the Air Force. He wrote an internal history of the Midas infrared missile warning satellite program and later wrote both an internal, and then a public, history of the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP). He published the Midas history in Quest magazine.

I met Cargill in the mid-1990s when he was a historian for the Air Force, when he had given me a thick copy of the Air Force history The Roswell Report. He had worked in multiple Air Force history positions and had written a book about the World War II military mission that had killed Japanese Admiral Yamamoto, the mastermind of the Pearl Harbor attack. Cargill did not consider the deliberate targeting of a senior military official to be a legitimate war mission.

By the late 1990s, he became a historian for the National Reconnaissance Office. I am sure that while in that job he collected records and probably conducted interviews on current NRO programs and that work will not be declassified for decades. But Cargill believed in making early Cold War history public, and worked on doing what he could. That was an unusual attitude for a military historian.

There was one project he began working on in the latter 1990s that was very significant and for which he deserves major credit: uncovering the history of top secret aircraft overflights of the Soviet Union in the early 1950s, before the well-known U-2 missions that began in 1956. During the 1990s, the history of the U-2 missions was being declassified by the CIA. But there were rumors of earlier flights, some using Royal Air Force aircraft, that had taken place in the early-mid-1950s. Although there was public information about “peripheral” missions that were intended to stay outside of Soviet territory and occasionally accidentally ventured into it, sometimes with tragic results, Cargill was interested in the missions that had deliberately penetrated Soviet airspace. Only one or two of them were known, but there were hints that several more had been undertaken. Initially, Cargill began digging through classified records but did not manage to find anything significant. Fortunately, he kept at it.

Like many historians, Cargill was partially motivated by what he saw as bad or sloppy history. A historian had written an article claiming that a top US Air Force general was using these reconnaissance flights to start World War III, figuring that Strategic Air Command would then flatten the Soviet Union—not much different than General Jack D. Ripper in Dr. Strangelove. Cargill didn’t believe that, and wanted to uncover the truth.

| We arrived at the location and saw the camera sitting on top of its pallet. For me, this was like uncrating the Ark of the Covenant at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark. |

Eventually, Cargill’s dogged determination bore fruit and he began to learn about pilots who had conducted some of these missions. There were few official records, possibly because the missions were so secret that nothing had been written down in the first place. But he did find people who were involved, and eventually held a history symposium in early 2001. That led to a proceedings. What he had found was many more flights than historians had suspected, but no indication that these were part of a coordinated campaign. Indeed, in some cases military commanders may have acted without senior approval. By the U-2 era and later, overflights became much more coordinated and centralized, as presidents did not want to risk war because some local commander did something stupid. Cargill’s work made possible the books that have been written since then on early Cold War era reconnaissance overflights, adding tremendously to the historical record.

Cargill was friendly, but also a bit of a curmudgeon. He was not fond of non-government historians like me writing about still classified programs based upon limited information; he believed that they should wait until the information was officially declassified, even if that meant waiting only three or four decades more. His view was that a partial history was worthless and that we should wait until the more complete history could be told. I was a bit annoyed by his attitude, in part because it meant that for certain subjects only the government could ever tell the story, but we never discussed it much. Part of the problem was that few official military historians cared about making their work public, meaning that certain subjects, like the Air Force’s space history, remained largely unknown. But Cargill did have a track record of producing public histories and wasn’t just talk.

I have one fun memory of Cargill. Probably in 2002 he and I were invited to go to a storage facility for the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. They were preparing to open the new Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Museum near Dulles International Airport, and part of the preparations for that involved doing a full inventory of the museum’s holdings. A curator had pulled out an artifact that had been in storage for 30 years, the panoramic camera for the canceled Apollo 18 mission. The PanCam was derived from a camera built by Itek and developed for the SR-71 and the U-2 reconnaissance planes. We arrived at the location and saw the camera sitting on top of its pallet. For me, this was like uncrating the Ark of the Covenant at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark. It was about a meter and a half long and a meter wide and gleaming white, looking brand new, and beautiful.

Alas, that camera has never been put on display at the Smithsonian. Cargill mentioned that he had about seven more of the aircraft version sitting in a classified warehouse, and he was hoping he could get them declassified and donated to museums. The guy had some cool toys, and he wanted to share.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.