Review: The Space Launch Systemby Jeff Foust

|

| “The biggest integration job on this vehicle was designing around existing hardware,” Lyles recalled. “The only element that we could have complete control over was the core stage.” |

Then Congress intervened. An amendment to the budget reconciliation bill introduced in June by Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX), chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee, would add $4.1 billion to procure SLS vehicles for Artemis 4 and 5. “The SLS is the only human-rated rocket available that can get humans to the Moon,” a committee fact sheet stated. “Importantly, this funding would not preclude integrating new, commercial options if and when they become available.” That provision made it into the bill that was signed into law July 4.

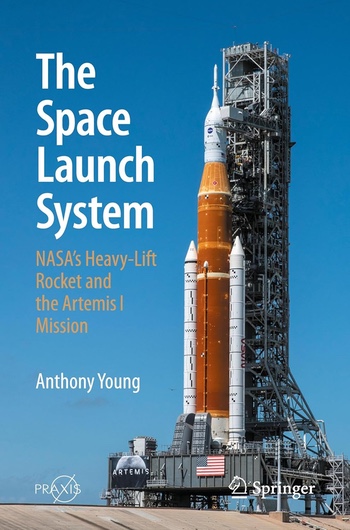

As we approach the 15th anniversary of the passage of the NASA authorization act directing NASA to develop a heavy-lift rocket designated the Space Launch System (see “Milestones and transitions”, The Space Review, October 4, 2010), it is worthwhile to reflect on what SLS has, and has not, achieved during that span. The Space Launch System by Anthony Young provides a detailed, but imperfect, overview of the development of the rocket through its first—and, to date, still only—flight.

Young starts with a chronological approach reviewing the Constellation program and the debates early in the Obama Administration that led to cancelling Constellation while preserving Orion and turning the Ares rocket program into SLS. Later chapters explore various elements of the SLS, including the core stage, boosters, and upper stages, culminating with an account of the Artemis 1 mission in 2022.

Young relies primarily on news articles and official documents for much of the book’s material, which turns some passages into fairly workmanlike, dry tick-tocks of various reviews and testing milestones. An exception is material from an interview with Garry Lyles, chief engineer of SLS, who provides insights particularly into the early development of the vehicle.

That includes a fairly blunt assessment of the approach to leverage shuttle-derived and other existing hardware to develop SLS, an approach advocates argued would be the fastest way to field the vehicle. “The biggest integration job on this vehicle was designing around existing hardware,” Lyles recalled. That included the Orion spacecraft, despite it still being in development itself. “The only element that we could have complete control over was the core stage.”

| SLS lies at one end of the spectrum of launch vehicle development: traditional contractors, traditional contracts, and an approach that calls for extensive analysis and testing before even thinking about a launch. |

While the book is in many respects comprehensive in tracking the development of the SLS, it has two flaws. One is a surprisingly poor job by the publisher editing of the book. In the first chapter alone, there are typos such as references to former NASA administrator “Dan Golden” and former deputy administrator “Fred Gregor” as well as the “Area 1-X” rocket. The chapter also mentions a proposed upper stage with a “27.5 m diameter”; from the context of that section, it should be 27.5 feet. It is disappointing that a major publisher like Springer did not perform a better copyedit of the book.

The other is that the book does not attempt to assess the state of the SLS program after a decade and a half. The book ends rather abruptly with a review of the “superlative performance” of the rocket on Artemis 1 in 2022. The rocket did perform very well on Artemis 1, and it has neither been the cause of delays in Artemis 2—caused by issues with Orion, particularly its heat shield—nor is on the critical path for Artemis 3. But is that performance worth the tens of billions spent on the program since its inception?

SLS lies at one end of the spectrum of launch vehicle development: traditional contractors, traditional contracts, and an approach that calls for extensive analysis and testing before even thinking about a launch. At the opposite end is SpaceX’s Starship: a vertically integrated company using private funds and fixed-price contracts and a far more iterative approach that accepts, and even embraces, launch failures while testing. What is the right approach? The answer hopefully will become clear in the next few years.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.