The intersection of cultural beliefs and mythos with non-governmental space activities and its potential impact to national interests and great power competitionby >Michael J. Listner

|

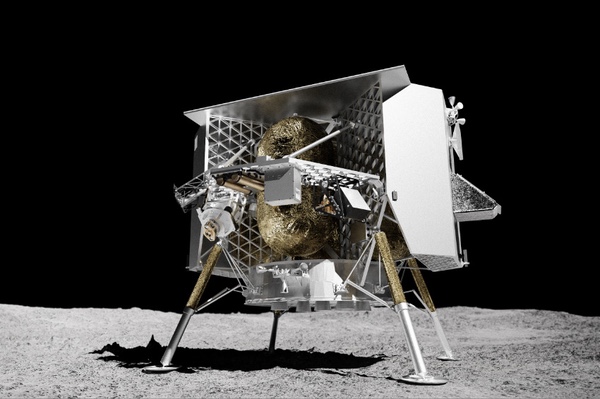

| While the mission was unsuccessful, the policy issues it raised are relevant to future non-governmental activities involving the Moon. |

It was the payload of cremated human remains that prompted the concern of the Navajo Nation, which the Tribe articulated in a December 21, 2023, letter to the Secretary of Transportation, the Assistant Secretary Tribal Affairs, and the NASA administrator.[1] The letter asserts NASA disregarded a prior agreement made with the Tribe vis-à-vis the religious and cultural significance of the Moon to indigenous cultures when it “approved” the mission. The letter also claimed NASA and the Department of Transportation disregarded an Executive Order relative to tribal relations and an MOU on the protection of indigenous sacred sites.

While the mission was unsuccessful and the spacecraft and its payload never reached the surface of the Moon, the policy issues it raised are relevant to future non-governmental activities involving the Moon. This essay will brief readers on the legal and cultural basis of the contentions made by the Navajo Nation, discuss its legal and policy significance and the potential implications on non-governmental space to include how the Tribe’s claims could become an implement of lawfare and hybrid warfare for state actors as part of great power competition.

Legal status of the Navajo Nation and other Native American tribes

The Navajo Nation is an independent political body that holds sovereign authority of its lands and is not subject in most cases to the laws of the State of Arizona. The primary source of US recognition of the sovereign status of the Navajos and other indigenous tribes comes through treaties. In the case of the Navajo Nation, the Treaty Between the United States of America and the Navajo Tribe of Indians, which was ratified on July 25, 1868, is the legal agreement establishing sovereignty for the Navajo Nation.

The US Constitution reenforces the status of the Navajo Nation as a sovereign nation in the eyes of the federal government via Article VI:

“This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.”[2]

The Constitution further recognizes the sovereign status of the Navajo Nation and other indigenous tribes in Article I, Section 8 , where it stipulates one of the powers of Congress to “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes.”[3]

The sovereign status of the Navajo Nation and other indigenous tribes has been upheld by the federal courts in a multiplicity of cases, including Williams v. Lee, 358 U.S. 217 (1959), Warren Trading Post v. Tax Comm'n, 380 U.S. 685 (1965), McClanahan V. Arizona Tax Comm'n State 411 U.S. 164 (1973), United States v. Wheeler, 435 U.S. 313 (1978), Merrion v. Jicarilla Apache Tribe, 455 U.S. 130 (1982), New Mexico v. Mescalero Apache Tribe, 462 U.S. 324 (1983), and Kerr-McGee Corp. v. Navajo Tribe, 471 U.S. 195 (1985). Native American tribes also enjoy sovereign immunity from lawsuits, unless that immunity is waived.[4]

The sovereignty of the Navajo Nation and other Native American Tribes is not absolute. For example, Article IX of the Navajo Treaty delineates concessions made by the Navajos in consideration of the legal obligations made by the US government. Moreover, Article I of the Navajo Treaty permits the US to prosecute crimes against the Navajos and crimes committed by Navajos under US law and in US Courts. However, the exercise of US jurisdiction and laws over criminal activity does not negate the sovereignty of the Navajo Nation to punish violations of tribal law.[5]

The sovereignty of the Navajo Nation extends to its lands with exception to the stipulations in Article IX. There is also an argument whether Native sovereignty and by extension tribal law extends to the airspace above its land as well and whether the federal government or tribal governments have jurisdiction.[6] Curiously, there have been rumblings that tribal sovereignty, including that of the Navajo, extends to outer space and the Moon. This so-called Tribal Space Sovereignty has no legal basis but appears to have its foundation in the cultural and religious traditions of Native American tribes.[7]

Native American cultural and religious significance of the Moon[8]

The Tribe’s letter states its concern about the Peregrine mission as follows:

“It is crucial to emphasize that the Moon holds a sacred position in many indigenous cultures, including ours. We view it as a part of our spiritual heritage, an object of reverence and respect. The act of depositing human remains and other materials, which could be perceived as discards in any other location, on the Moon is tantamount to desecration of this sacred space.”

This concern articulates the spiritual and cultural significance that both the Sun and the Moon have to Native Americans.

“Navajo spirituality is deeply intertwined with the natural elements that surround the Navajo people. Among these, the celestial bodies—the Sun and the Moon—hold a significant place in their mythology and cultural practices. These heavenly entities are viewed not only as physical objects but also as key players in the cycle of life, influencing both the natural world and the spiritual realm.”[9]

Specific to the Moon:

“The moon is often seen as the ‘mother’ of all creation in many Native American cultures. It represents femininity, intuition, and spiritual connectedness. Many native traditions hold special moon ceremonies to celebrate its power.”[10]

Both the Sun and the Moon hold significance together:

“The Sun and Moon embody the Navajo worldview of duality, where opposites coexist and support one another. This concept is evident in various cultural practices and beliefs, influencing everything from personal relationships to societal structures.”[11]

It is in the context of the cultural and religious significance of the Moon to Native American culture that the Tribe’s letter will be examined.[12]

The Navajo Nation’s letter, contentions and cited authorities

The root of the Tribe’s grievance over the Astrobotic mission stem from a commitment NASA made with the Navajo Nation when the Lunar Prospector, which contained the cremated remains of Eugene Shoemaker, was intentionally crashed at the lunar south pole. After the Navajo Nation raised its concerns, NASA issued a letter of apology and made a commitment to consult the Tribe before authorizing further missions to the Moon carrying human remains.[13] The Tribe’s letter enunciates this:

“This issue echoes back to the late 1990s, when the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (“NASA”) sent the Lunar Prospector, carrying the remains of Eugene Shoemaker, to the Moon. At the time, Navajo Nation President Albert Hale voiced our objections regarding this action. In response, NASA issued a formal apology and promised consultation with tribes before authorizing any further missions carrying human remains to the Moon.”

The Tribe’s letter goes on to implicate NASA and asserts the Department of Transportation is at fault as well:

“Yet, it appears from the information at hand that NASA has not upheld this commitment. Moreover, it seems the Office of Commercial Space, under the U.S. Department of Transportation (“USDOT”), also failed to engage in consultation with the indigenous tribes prior to issuing the payload certificate for this launch.”

The Tribe cites three authorities. First, the Tribe points to an executive order and a promise based on that order made by the Biden Administration on January 26, 2021, to consult with tribes on matters that impact tribes. The Tribe points to these two authorities as the rationale for criticizing the Department of Transportation in particular for not consulting with the Navajo Nation about authorizing the mission:

“Not only has NASA previously committed to consultation with us, but also the broader Biden Administration promised to engage in consultation on matters that impact tribes, as per the Memorandum on Tribal Consultation and Strengthening Nation-to-Nation Relationships dated January 26, 2021. This memorandum reinforced the commitment to Executive Order 13175 of November 6, 2000.”

Executive Order 13175 was issued by President Clinton on November 6, 2000, and published on November 9, 2000. The purpose of the EO as articulated in the introduction is:

“…to establish regular and meaningful consultation and collaboration with tribal officials in the development of Federal policies that have tribal implications, to strengthen the United States government-to-government relationships with Indian tribes, and to reduce the imposition of unfunded mandates upon Indian tribes;”[14]

EO 13175 directs executive agencies to respect tribal sovereignty, grant tribal governments maximum discretion with respect to statutes and regulations, encourage tribes to develop their own policies to achieve program objectives, defer to tribes to establish standards, and consult with tribal authorities when determining whether federal standards or alternatives should apply.[15] EO 13175 also requires agencies to:

“…have an accountable process to ensure meaningful and timely input by tribal officials in the development of regulatory policies that have tribal implications.”[16]

The Tribe next cites a presidential memorandum signed by President Biden on January 26, 2021. The Memorandum on Tribal Consultation and Strengthening Nation-to-Nation Relationships is a directive that does not appear to be an executive order. The effect of the Memorandum is to recite, reenforce, and offer further guidance on EO 13175.[17]

The Tribe’s letter further emphasizes the requirement for a consultation pointing to a memorandum of understanding entered into by the Biden Administration:

“Additionally, the Memorandum of Understanding Regarding Interagency Coordination and Collaboration for the Protection of Indigenous Sacred Sites, which you and several other members of the Administration signed in November 2021, further underscores the requirement for such consultation.”

The Memorandum of Understanding Regarding Interagency Coordination and Collaboration for the Protection of Indigenous Sacred Sites was signed on November 9, 2021.[18] The MOU recites applicable federal law and executive orders, including EO 13175, to sacred indigenous sites. Specifically, the Tribe’s letter seems to indicate the consultation requirement in paragraph II(2):

“Develop and enhance best practices and policies for meaningful consultation with Indian Tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations that give clear guidance on the duties and responsibilities of Federal agencies to address and incorporate traditional Indigenous knowledge and views when assessing the impact of Federal actions on sacred sites;”

Specifically, the Tribe points to the Administration’s alleged disregard for the progeny of the MOU:

“It seems that the Best Practices Guide for Federal Agencies Regarding Tribal and Native Hawaiian Sacred Sites, which was recently developed and released as a result of the above-mentioned MOU, has not been adequately considered concerning the upcoming launch. The Guide explicitly recognizes that sacred sites can consist of ‘places that afford views of important areas of land, water, or of the sky and celestial bodies.’”

However, the Tribe’s application of The Guide is dubious and taken out of context. The Guide does mention celestial bodies but not in the context of the Tribe’s assertion a consultation was required. The full language in The Guide reads as follows:

“Sacred sites can consist of geological features, bodies of water, archaeological sites, ceremonial sites, places of origin, birthing grounds, burial locations, stone and earth structures, or other features or combinations of features. Examples might include, mountains, volcanoes, rocks, dunes, cave systems, animal tracks, swamps, coral reefs, groves, petroglyphs, burial sites, boarding school grounds, battlegrounds and massacre sites, trails, shelters, traditional harvesting areas, or places that afford views of important areas of land, water, or of the sky and celestial bodies.” [emphasis added]

In other words, “places that afford views of important areas of land, water, or of the sky and celestial bodies” refers to terrestrial places as “sacred places” that allow for viewing of celestial bodies, including the Moon; it does not refer to the Moon as a “sacred place” in the context of the need for consideration in The Guide. At best, mentioning this provision of The Guide in the letter was error on the part of the Navajo Nation; at worst it was recited in an attempt to support the Tribe’s narrative.[19]

The Tribe’s letter concludes with a petition to delay the launch pending a consultation:

“Given these circumstantial insights, we request the launch be delayed and immediate consultation take place. We believe that both NASA and the USDOT should have engaged in consultation with us before agreeing to contract with a company that transports human remains to the Moon or authorizing a launch carrying such payloads.”

The Biden Administration reportedly agreed to a consultation, but the launch was not delayed. Apparently, the Tribe’s interests either did not constitute an “imperative national need” or if it did, that “imperative national need” did not justify preempting the launch.[20]

The concern in entertaining a consultation for the Tribe is whether the Administration may have opened non-governmental space activities to the risk of intervention by Native American Tribes for future missions to the Moon, including space resource activities.[21]

The potential consequences of tribal claims to non-governmental activities

The Navajo Nation’s grievance and request for consultation and the Administration’s acquiescence for a consultation brings into question how the Navajo Nation or other Tribes will respond to future non-governmental space activities involving the Moon, including space resource activity: will they insist on consultations prior to the launch of non-governmental missions to the Moon? Alternatively, will Native American tribes seek consultation as part of the licensing process and will policy decisions mandate that Native American spiritual and cultural concerns be given weight during the review of a launch license, including the policy review under 14 CFR §§415.23(a) and 415.23(b)(2)?[22]

| Will Native American tribes seek consultation as part of the licensing process and will policy decisions mandate that Native American spiritual and cultural concerns be given weight during the review of a launch license? |

Unless Congress specifically legislates the extent to which Native American cultural and spiritual concerns will weigh into the policy review (if at all) for a launch license or mission authorization, future administrations could mandate through executive order policy considerations that are influenced by academia and NGOs. These policy considerations could give inordinate weight to Native American cultural concerns and potentially be a deciding factor as to whether a launch license for a specific non-governmental space activity on the Moon would be approved.

Accordingly, Congress should be cognizant of the potential impact of Native American spiritual and cultural objections and address what weight will be given to those concerns not only in the present licensing process for non-governmental activities but also any “mission authorization” schemes that might be considered to overhaul Article VI licensing of non-governmental space activities, especially with activities involving the Moon. This would include evaluating federal recognition of the veracity of tribal sovereignty, including claims of Tribal Space Sovereignty, with regards to outer space and celestial bodies.[23]

Consequently, the Navajo Nation’s letter and petition for consultation exposes a very real and potential issue that will have to be addressed as non-governmental space activities, including space resource activities, on the Moon become more prolific. More concerning is whether consenting to a consultation for the Navajo Nation may have opened the door for geopolitical adversaries to interfere with non-governmental space activities on the Moon utilizing hybrid warfare as part of great power competition with the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

Chinese cultural beliefs and hybrid warfare

The Moon plays a large part in the traditions of many cultures aside from Native American culture. The Tribe’s letter acknowledges this: “It is crucial to emphasize that the Moon holds a sacred position in many indigenous cultures, including ours.”

Chinese culture has strong ties to the Moon.[24] As noted by an article in the Asian Journal:

“Central to the interpretation of lunar symbolism in Chinese culture is the philosophy of Yin and Yang. The concept of Yin and Yang represents the harmonious balance of opposing forces in the universe. The moon, with its alternating phases of light and darkness, exemplifies this delicate equilibrium. It is seen as a manifestation of Yin energy, representing the feminine, passive, and introspective aspects of existence. Conversely, the sun embodies Yang energy, symbolizing the masculine, active, and outwardly expressive forces. The interplay between Yin and Yang, exemplified by the moon’s waxing and waning, resonates deeply within the Chinese philosophical framework, shaping their understanding of the cosmos and human nature.”[25]

Unlike the symbolism that is prevalent in Native American culture, Chinese culture also consists of deities on the Moon and the mythology surrounding them.

“At the forefront of lunar deities in Chinese mythology stands Chang’e, the Moon Goddess. According to ancient legends, Chang’e was once a mortal woman who attained immortality by consuming the elixir of life. As a result, she ascended to the moon, where she resides to this day. Chang’e is often depicted as a graceful and ethereal figure, radiating beauty and serenity. Her legend is intimately linked to the Mid-Autumn Festival, where she is celebrated as the central figure.”[26]

“Beyond Chang’e, Chinese mythology is replete with other lunar deities, each with their unique roles and symbolism. One notable figure is the Jade Rabbit, also known as Yutu, who resides on the moon alongside Chang’e. According to folklore, the Jade Rabbit accompanies Chang’e and pounds the elixir of immortality using a mortar and pestle. The image of the Jade Rabbit is deeply ingrained in Chinese culture, representing companionship, diligence, and longevity.

Another significant lunar deity in Chinese mythology is Wu Gang, an immortal woodcutter. Legend has it that Wu Gang was banished to the moon as a form of punishment for his arrogance. He is condemned to chop down a celestial cassia tree, which magically regenerates every time he strikes it. The tale of Wu Gang reflects the Chinese belief in the cyclical nature of life and the pursuit of self-improvement through diligence and perseverance.”[27]

| By granting a consultation to the Navajo Nation, the US may have opened the door for state actors and State Parties to the Outer Space Treaty like the PRC to use their culture and mythos surrounding the Moon and outer space to apply hybrid warfare tactics. |

The role of the Moon in Chinese culture is significant and seemingly more robust than the mythos and cultural connection binding Native American culture. The PRC, for its part, utilizes this mythos in its space program with its Chang’e series of lunar landers and the Jade Rabbit (Yutu) rover. The PRC is also utilizing Chinese mythology with its space station, Tiangong, which translates to “Heavenly Palace”, which refers to the residence of the deity who holds supreme authority over the universe in Chinese mythology, the Celestial Ruler.[28] While the PRC’s application of its culture and mythos to outer space is designed to influence a broader global audience, it also serves to shape a political narrative about the propriety of establishing sovereign claims to outer space and celestial bodies, which is a similar tack the PRC is utilizing to justify “historical and cultural claims” to swaths of the South China Sea.

By granting a consultation to the Navajo Nation, the US may have opened the door for state actors and State Parties to the Outer Space Treaty like the PRC to use their culture and mythos surrounding the Moon and outer space to apply hybrid warfare tactics, including lawfare, to frustrate US non-governmental space activities and by extension affect US national interests. Unlike the Navajo Nation, the PRC is a sovereign state and has geopolitical standing that includes being State Party to the Outer Space Treaty, which the Navajo Nation and other Tribes do not belong to nor have legal standing to assert.

Thus, a diplomatic communique from the PRC raising cultural issues would have greater influence than the claims of a Native American tribe. This raises the specter the PRC could see an opportunity to employ hybrid warfare to hinder US non-governmental activities and specifically those involving the Moon. The PRC has utilized hybrid warfare as doctrine for over 20 years through the Three Warfares in multiple domains, so it is not out of the question nor is it improbable the PRC would employ hybrid warfare using its culture to delegitimize nongovernmental space activities.[29]

Consider this hypothetical:

A US non-governmental applies for a license and authorization to send a lander and rover to the south pole of the Moon to seek out and harvest water ice that it will later sell pursuant to Title 51, Chapter 513 and specifically, 51 U.S.C § 51303.[30] The PRC, which is aware of the planned non-governmental mission, seeks to delay the authorization so that its own mission can be prepared so that it arrives at the lunar south pole first to create a legal and political impediment that subsequent space resource missions would have to overcome.

Presuming US policy would give significant consideration to cultural and religious concerns when performing a policy review to obtain a launch license for the mission, the PRC makes a formal request through its Embassy in Washington, DC, to raise a concern about the proposed non-governmental mission and its disrespect to Chinese culture.[31] Simultaneously, the PRC utilizes the media, academia, and NGOs to create a political narrative on the sensitivity of the Chinese to its culture and mythos surrounding the Moon as well as using soft power through its seat in the UN and COPUOS to decry the insensitivity of the US non-governmental mission. Seeing this, Native American tribes file a concurrent protest and seek a delay of the mission until a consultation can be made as to the mission’s effect on Native American cultural beliefs.

This stratagem would create negative political optics for the US and stall the licensing of the non-governmental mission while the US consults with the PRC delegation and Native American tribes. The effect is the tempest created by the PRC effectively delays the authorization or leads to denial of a license pending further assurances by the US and the non-governmental. In the meantime, the PRC completes its preparations for the mission, launches, and successfully lands another Chang’e spacecraft with a rover to create a legal placeholder to stymie a future claim of water ice by a US non-governmental.

Another possible tactic would be for the PRC to invoke its right to consultation under Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty before the mission was launched.[32] The PRC could make the argument US authorization for the Peregrine lander or the launch itself would be done without due regard to Chinese culture surrounding the Moon. The PRC could further elaborate their claim asserting the mission could cause potentially harmful interference with future space activities the PRC was planning to enhance its cultural connection to the Moon. Given “potentially harmful interference” is a hair-trigger standard of care, the PRC could easily invoke its right to consultation.[33]

Such a move would be a misapplication of Article IX, but this wouldn’t stop the PRC from misusing the Outer Space Treaty as it has done so before.[34] Overall, while not likely to be accepted on the merits, the procedure of such a move could at least cause a non-governmental mission to be delayed or extract concessions and modifications that would dilute the mission itself. However, this lawfare approach has the added danger of state practice that would be created with the duty to consult, the right to consultation and the trigger of “potentially harmful interference” in Article IX, which makes it likely the PRC would be cautious employing this tactic.[35]

One additional thought in the world of hypotheticals:

What if it was the PRC and not the Navajo Nation who, instead of sending a letter, made a diplomatic request to the US seeking the January 2024 launch be delayed so that cultural concerns with the mission could be addressed. Given the PRC is a State that has geopolitical standing and is a State Party to the Outer Space Treaty, would the US have invoked 51 U.S.C. § 50910 and decided there was an “imperative national need” to preempt the launch to address the PRC’s concerns? Certainly, the national security concern of the loss of the launch window for the non-governmental payload and its customers by the preemption could be considered minimal.[36] However, the preemption of the launch could have delayed the certification of a new launch vehicle, which would have affected national security payloads manifested thereby making it a significant national security concern that would have to be considered.[37]

It would have been a political decision as to whether the PRC’s request would rise to the level of an “imperative national need” that would offset the national security interest of certifying a new launch vehicle. What is certain whatever the decision might have been, the mere act of entertaining the PRC request would be an exercise in lawfare where the PRC could at the very least gauge the usefulness of using its cultural heritage as an implement of hybrid warfare.

The purpose of these hypotheticals is to expound how a state like the PRC could use its cultural and spiritual beliefs relating to the Moon (and outer space) as an implement in hybrid warfare to interfere with non-governmental space activities that are significant to US national interests. More to the point, it signals to lawmakers and policymakers the dangers of entertaining consultations on cultural concerns surrounding non-governmental space activities without considering the precedent it would set for adversaries to engage in hybrid warfare.

Closing thoughts

Non-governmental space activities are ushering innovative technologies and capabilities that will expand human influence in outer space. Concurrently, these capabilities are challenging existing law and policy, and portend the need for both to adapt as these proficiencies escalate. Caught in this vortex is the consideration of cultural and spiritual beliefs surrounding outer space and celestial bodies, including the Moon. The Navajo Nation’s letter appears to have made this a more visible issue and could be the impetus for further concerns being made not only by Native Americans but other cultures as well.[38]

| Cultural beliefs surrounding outer space, including the Moon and celestial bodies, may seem trivial in the grand scheme of permitting non-governmental space activities, but to Native American culture these traditions are a way of life. |

Will the US address future cultural concerns as they arise or take a proactive stance by incorporating cultural and religious concerns into decisionmaking for licensing or authorization of non-governmental space activities? In the case of Native Americans, would this mean the Department of the Interior and the Office of Indian Affairs become a de facto Article VI authorizing agency along with the FAA, FCC, and NOAA?[39] If so, how much consideration should cultural concerns be given and will it be weighed in such a way that it will not be considered a tipping point to reject a launch license or mission authorization?

These are questions that need to be addressed by policy makers but more critically dealt with by Congress. With the means of Article VI authorization and continuing supervision being debated the question of the influence of cultural beliefs and spirituality on the sanction of future non-governmental space activities should be addressed.[40]

Whether and to what extent Native American culture is weighed in decisionmaking with regards to non-governmental space activities remains to be seen. Cultural beliefs surrounding outer space, including the Moon and celestial bodies, may seem trivial in the grand scheme of permitting non-governmental space activities, but to Native American culture these traditions are a way of life. From the perspective of Native Americans this is an issue that rightly evokes emotion. However, it is judicious that any decisionmaking process should also be viewed pragmatically and consider the potential geopolitical pitfalls that could emerge in the scope of deciding whether to and to what extent cultural traditions and beliefs should influence future non-governmental space activities.

Endnotes- The Coalition of Large Tribes also authored a letter dated January 4, 2024, to the Secretary of Transportation and the NASA Administrator supporting the Navajo Nation’s position.

- U.S. Const. art. VI, para. 2.

- U.S. Const. art.1, § 8, para. 3.

- “The Supreme Court has repeatedly declared a presumption favoring tribal sovereign immunity.” Demontiney v. U.S. ex rel. Dep't of Interior, Bureau of Indian Affs., 255 F.3d 801, 811 (9th Cir. 2001). “As a matter of federal law, an Indian tribe is subject to suit only where Congress has authorized the suit or the tribe has waived its immunity.” See Kiowa Tribe of Okla. v. Mfg. Techs., 523 U.S. 751, 754, 118 S.Ct. 1700, 140 L.Ed.2d 981 (1998).

- See Williams v. Lee, 358 U.S. 217, 221-222 (1959).

- See generally, William M. Haney, Protecting Tribal Skies: Why Indian Tribes Possess the Sovereign Authority to Regulate Tribal Airspace, American Indian Law Review, Vol. 40, No. 1, 2016.

- The concept of Tribal Space Sovereignty has been asserted by some in the Native American community but has not been adequately defined nor explained. This concept is being used as the rationale for Native American participation in the Artemis Accords and other NASA activities involving outer space and the Moon.

- The author provides this information as context for discussion of the Tribe’s letter, its assertions and its implications.

- “The Role of the Sun and the Moon in Navajo Spiritual Beliefs”, Native American Mythology, February 8, 2025..

- Ibid.

- Id.

- Of course, Native American culture is not the only one that gives significance to the Moon (as will be elaborated on later.) The Jet Propulsion Laboratory produced a short guide to Moon myths around the world.

- The author was unable to locate a copy of this letter and relies on second-hand narrative for this information.

- Exec. Order No. 13175, 65 Fed. Reg. 67249

- Id. at 67250.

- Id.

- See generally, Memorandum on Tribal Consultation and Strengthening Nation-to-Nation Relationships, 86 Fed. Reg. 7491-7492.

- The Memorandum of Understanding Regarding Interagency Coordination and Collaboration for the Protection of Indigenous Sacred Sites was signed by multiple agencies, including the Department of Transportation.

- The MOU has no legal effect nor does it amend the Treaty signed with the Navajo Nation.

- If the Administration decided the Tribe’s concern met the level of “imperative national need” and preempted the launch, the Secretary of Transportation would have been required under 51 U.S.C. § 50910(c) to submit a report to Congress within seven days includes explaining the circumstances that justified the decision to preempt launch and a schedule ensuring the prompt launch of the payload.

- A representative from the now defunct NASA Office of Technology Policy and Strategy attended the National Congress of American Indians on June 5, 2024, and reportedly posed the following question to the Native American audience: “How do we go into space responsibly?” This could have been an attempt at a compromise over the complaint filed by the Navajo Nation, but it does not give nor impute sovereignty or legal standing.

- § 415.23 Policy review. (a) The FAA reviews a license application to determine whether it presents any issues affecting U.S. national security or foreign policy interests, or international obligations of the United States. (b) Interagency consultation. (2) The FAA consults with the Department of State to determine whether a license application presents any issues affecting U.S. foreign policy interests or international obligations.

- See supra note 7.

- “Chinese” is used in the context to describe Chinese culture as a whole and relationship to the Moon and other celestial bodies and does not delineate between the Peoples Republic of China or Taiwan.

- Alexie Juagdan, The Moon in Chinese Culture: Symbolism and Significance, Asian Journal USA, June 30, 2023.

- Ibid.

- Id.

- See Molly Silk, China is using mythology and sci-fi to sell its space programme to the world, The Conversation, June 25, 2021.

- See generally, Michael J Listner, China, Article V, Starlink, and hybrid warfare: An assessment of a lawfare operation, The Space Review, September 11, 2023.

- “A United States citizen engaged in commercial recovery of an asteroid resource or a space resource under this chapter shall be entitled to any asteroid resource or space resource obtained, including to possess, own, transport, use, and sell the asteroid resource or space resource obtained in accordance with applicable law, including the international obligations of the United States.”

- See 14 CFR §§415.23(a) and 415.23(b)(2)

- Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, October 10, 1967, art. ix.

- See Michael Listner, The Paradox of Article IX and National Security Space Activities, Air University AETHER, pp. 25-27, Vol 1, No. 4, January 12, 2023.

- See generally, Michael J Listner, China, Article V, Starlink, and hybrid warfare: An assessment of a lawfare operation, The Space Review, September 11, 2023.

- Id.

- See 51 U.S.C. § 50910(c).

- Related to a decision to preempt the launch of a non-governmental payload is the matter of cost both to the payload owner and the launch provider. Both are providing a private service and the costs, including standing down launch activities, storage and the maintenance of the launch vehicle and payload until a new launch window could be accommodated, etc., could be interpreted as a taking under the due process clause of the 5th Amendment of the Constitution. “No person shall be…. deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” U.S. Const. amend. V.

- The Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti o Waitangi), which grants sovereignty to the Māori, has been the basis of cooperation between the Crown and the Māori to include their input on policy matters. This is demonstrated in New Zealand’s recent National Space Policy, which was developed in cooperation with the Māori to ensure their cultural values were taken into consideration.

- Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, October 10, 1967, art. vi, 18 UST 2410.

- Executive Order 14335 enacted August 11, 2025, by the Trump Administration could provide a stopgap measure to mitigate the influence of cultural beliefs on the non-governmental space activities. Specifically, Sections 3 and Section 5 of the E.O. could be utilized to that end.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.