Go faster, somehowby Jeff Foust

|

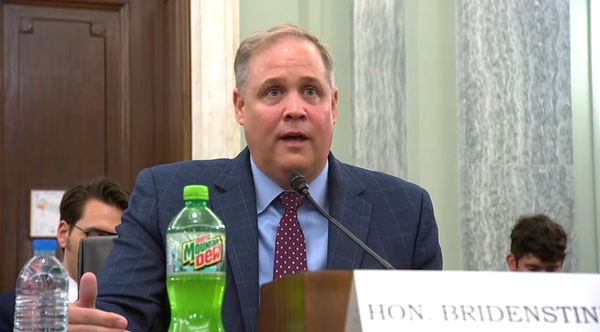

| “It is highly unlikely that we will land on the Moon before China,” Bridenstine declared. |

The difference was that, this time, he was on offense, not defense. In past Senate Commerce Committee hearings when he led NASA, he faced tough questions from senators critical of agency programs. This time, it was Bridenstine criticizing the agency, in particular its approach to exploration that dated back to his tenure as administrator.

“The purpose of this hearing is, are we going to be able to get to the Moon first?” he said, referencing the perceived space race between the United States and China about who will next land astronauts on the Moon.

“Look at the architecture we have developed to land American astronauts on the Moon. Look at the architecture. It is extraordinarily complex,” he said. “It is highly unlikely that we will land on the Moon before China.”

His issues with the Artemis architecture were not with the Space Launch System, he said, or the Orion spacecraft. “I have been critical of both in the past, in front of this committee and in other places,” he said of them, but argued both had overcome past problems.

“Here’s what we don’t have today. We don’t have a landing system for the Moon,” he continued. NASA, of course, does have not one but two landing systems in development: SpaceX’s Starship and Blue Origin’s Blue Moon Mark 2, both part of the Human Landing System (HLS) program.

The selection of Starship, though, has faced some more recent criticism because of delays in its development. Even with a successful test flight about a week before the hearing (see “Back in the win column”, The Space Review, September 2, 2025), its development has fallen behind, with planned in-space propellant transfer tests—a key technology Starship missions beyond low Earth orbit—delayed from this year to next. That puts into question a NASA schedule that still calls for the Artemis 3 mission in mid-2027.

Bridenstine, in his opening remarks, criticized that need for in-space refueling of a propellant depot. “We’ll need to launch—nobody really knows, nobody knows—but it could be up to dozens of additional Starships to refuel the first Starship,” he said. “By the way, that whole in-space refueling thing has never been tested, either.”

He added that, once that depot Starship fuels the lunar lander Starship, it’s unclear how long the lander version can then loiter in lunar orbit, waiting for the crew to arrive on an SLS-launched Orion.

Those criticisms are not new in general of the HLS version of Starship, but Bridenstine took them up a notch. “This is an architecture that no NASA administrator that I’m aware of would have selected if they had the choice,” he said.

His argument was that the selection of Starship for HLS was made in early 2021, after Bridenstine resigned at the end of the first Trump Administration and before Bill Nelson was confirmed by the Senate as the agency’s next administrator. During that interregnum, the agency was led by an acting administrator, the late Steve Jurczyk.

“I don’t know how this happens, but the biggest decision in the history of NASA, at least since I’ve been paying attention, the biggest decision happened in the absence of a NASA administrator,” he said.

The decision, though, was not officially the NASA administrator’s to make. The source selection authority—the NASA official formally responsible for that decision—was the associate administrator for human exploration and operations at the time, Kathy Lueders. She noted at the time that a major factor in selecting SpaceX, and neither other of the other two bidders, was that SpaceX offered a far lower price while getting similar or better technical and management scores (see “All in on Starship”, The Space Review, April 19, 2021).

That decision was upheld by the Government Accountability Office when those losing bidders, Blue Origin and Dynetics, filed a bid protest. Later, Blue Origin filed suit in the US Court of Federal Claims, only to lose there as well (see “Resetting Artemis”, The Space Review, November 15, 2021).

Regardless of who made the decision, that decision was made more than four years ago. “It’s a problem. It needs to be solved. And that puts us as a nation at risk,” he said.

| “We are in a new space race with China,” said Cruz. “The choices we make today will determine whether the United States leads in space or cedes space to an authoritarian regime.” |

However, Bridenstine’s testimony offered no potential solutions to the perceived problems with Starship. During the two-hour hearing, senators did not ask Bridenstine or other witnesses about how to address Starship delays even as they fretted about the prospect of China getting its astronauts on the lunar surface before NASA can return.

“We are in a new space race with China,” said Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX), chairman of the committee, in his opening remarks. “The choices we make today will determine whether the United States leads in space or cedes space to an authoritarian regime.”

It’s not clear what the options would be if NASA and/or Congress decided to make a change in a lunar lander architecture. At a House hearing in February, Dan Dumbacher, a former deputy associate administrator for exploration at NASA, suggested the agency replace Starship, at least for initial lunar landing missions, with “a simplified lander” that would not require multiple launches, although he did not go into details about the design.

In an op-ed last week, Dumbacher and two other former leaders of NASA human exploration programs, Doug Loverro and Doug Cooke, stated their concerns about the current architecture. “In fact, the number of technical hurdles SpaceX has thus far overcome pales in number and complexity to those that lay ahead,” they wrote. But the only concrete recommendation they offered was for NASA to create a “truly independent review team” to perform a 45-day assessment of the program to NASA, the White House, and Congress.

NASA’s current acting administrator, Sean Duffy, said comments that China would get humans to the Moon before NASA could return made him angry. (credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls) |

“Shade thrown on all of NASA”

NASA was not represented at the hearing, nor was SpaceX. (One of the original witnesses scheduled to testify was Dave Cavossa, president of the Commercial Space Federation, an industry whose members include SpaceX and Blue Origin. But Cavossa was informed several days before the hearing that the committee would instead have him testify at a future hearing on commercial space.)

Just before the hearing, though, NASA announced it was promoting one of its top officials working on Artemis. Amit Kshatriya, a former flight director who had been leading the agency’s Moon to Mars Program Office, was named associate administrator, the top civil service post at the agency. The move, NASA said in a statement, was intended to signal that it was placing exploration “at the very core of our agency.”

| “I’ll be damned if that is the story that we write,” Duffy said. “We are going to beat the Chinese to the Moon.” |

One of the witnesses at the hearing welcomed the news. “That sends an important message not just to NASA but to our international partners, even China, that we’re back, we have reignited the torch of Artemis, and we’re going to the Moon,” said Mike Gold, president of civil and international space at Redwire and a former NASA official. “NASA civil servants needed to hear that.”

NASA civil servants heard from both Kshatriya and acting administrator Sean Duffy the next day in an internal town hall. Duffy used the event to push back against Bridenstine’s testimony at the Senate hearing.

“There’s questions yesterday, actually, in a Senate hearing,” Duffy said, “as we had testimony that said NASA will not beat China to the moon.” He did not mention Bridenstine by name but made it clear he disagreed.

“That was shade thrown on all of NASA,” he said. “I was angry about it.”

He reiterated statements he has made frequently since taking the helm of the agency that he believed NASA would get astronauts back to the Moon—including the official 2027 date for Artemis 3—and do so before China landed its first crewed mission.

“I’ll be damned if that is the story that we write,” he said. “We are going to beat the Chinese to the Moon. We are going to make sure that we do this safely. We’re going to do it fast. We’re going to do it right.”

Neither Duffy nor Kshatriya, though, offered much detail about how they would do so beyond injecting a greater sense of urgency. “The first thing I’d say is everything, every meeting, every discussion you have, every day you wake up, ask yourself, ‘Is what I’m doing helping us get back to the Moon?’” Kshatriya said. “If it’s not, stop doing it. You’ll have my full support to stop doing it.”

Duffy, meanwhile, hinted NASA would reexamine the balance of risk and safety in the architecture. “We are safety driven and we should be safety driven,” he said. “But sometimes we can let safety be the enemy of making progress. We have to be able to take some leaps.”

He did, though, target another criticism of the Artemis architecture: its cost. “It’s important that we bring the cost down At $4 billion a launch, it becomes very challenging to have a Moon program,” he said, a reference to past cost estimates of a single SLS/Orion launch made by NASA’s inspector general.

He suggested NASA could look for ways to harness “a revolution in innovation in launches to space” as well as other partnerships to bring down mission costs. “We’re going to work with our partners to figure out a way that we can do more missions with the same amount of dollars.”

| “It’s important that we bring the cost down At $4 billion a launch, it becomes very challenging to have a Moon program,” Duffy said. |

That could put the agency into conflict with the same people on Capitol Hill who, the day before, were worried Starship would keep the United States from being the next to put astronauts on the Moon.

At the hearing, Cruz took credit for efforts in the budget reconciliation bill to add nearly $10 billion to NASA’s budget principally for exploration programs. That included funding for two more Space Launch System rockets after the administration proposed ending SLS and Orion after Artemis 3, as well as funding to finish the Gateway in lunar orbit.

“Any drastic changes in NASA’s architecture at this stage threaten United States’ leadership in space,” Cruz said in his opening remarks at the hearing. “Delays and disruptions only serve our competitors.” After outlining that funding in the budget reconciliation bill, he said that he would work with the administration “to ensure that those funds are utilized in full accordance with Congressional intent.”

So, is the problem with Artemis that parts of it, like Starship, are behind schedule and threaten American leadership in human space exploration? Or is the problem that other elements of it are so expensive that it is not sustainable, which could also American leadership in human space exploration? Or both? Without common agreement on the issues facing Artemis, there is little chance of figuring out how to solve them.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.