The greatest story on planet Mars: the sequelby Dwayne A. Day

|

|

The greatest story on planet Mars

The story had all the lurid qualities of a dime-store political thriller: top presidential advisor tells secret information to a high-priced prostitute who promptly sells the story to a reporter. As the disgraced advisor resigns in an embarrassing scandal, the story has earth-shattering consequences. Such was the rumor that circulated after the possibility of past life on Mars leaked to the press a week before the official announcement. It was a great story with only one minor flaw: it wasn’t true.

| The reporter who broke the news was Leonard David, and if anyone was going to break the story of life on Mars, it was going to be him. |

The word that a group of NASA and university scientists had found evidence of possible past life on Mars created a short-lived media frenzy within the United States as well as around the world. On Tuesday, August 6, 1996, two of the three major news networks in the United States led their broadcasts with stories on the Mars rock, despite the fact that they had no firm information on which to base their reports and no visuals which are so central to modern television reporting. That same day, in Washington and all over the United States, journalists struggled to get more information. Calling it a media feeding frenzy would be an understatement. Everyone wanted the story, and all they knew was that they had all been beaten to the punch by another reporter.

In the wake of the story, rumors circulated through space and media circles that the leak—coming two weeks before the officially planned announcement of the research team’s findings—was the result of some Washington, DC pillow-talk associated with a recent White House scandal. The lurid story, apparently even promoted by one of NASA’s scientists, couldn’t have been farther from the truth.

The reporter

The reporter who broke the news was Leonard David, and if anyone was going to break the story of life on Mars, it was going to be him. David is a veteran space reporter who has written for scores of magazines and trade journals and also served as editor for several space publications. He is probably the best-connected space reporter in the business, especially when it comes to Mars. David considers himself one of the original members of the “Mars Underground,” a group primarily centered in Boulder. Colorado, which has been dedicated to the exploration of the Red Planet for nearly two decades. David knows virtually everyone associated with Mars research.

Leonard David got the story from a reliable source at least a week before he wrote it. He submitted it to Pat Seitz, his editor at Space News, a weekly trade publication, on Friday afternoon, August 1. [1] He was a little unsure whether it would actually run in the paper, since he had already submitted two other articles that week, one on space tourism and the other on NASA research into wormholes. By the time he submitted a “life on Mars” story he figured his editor would have concluded that David had gone crazy. Thus, he wasn’t even sure the news-paper had decided to run the story until the following Monday, when he looked at a copy in the NASA library. It was carried on page two of the paper, in a section labeled “This Week” and usually reserved for late-breaking stories of no more than 150 words.[2] It was also carried on the newspaper’s website. A day later the story spread throughout the country and the world.

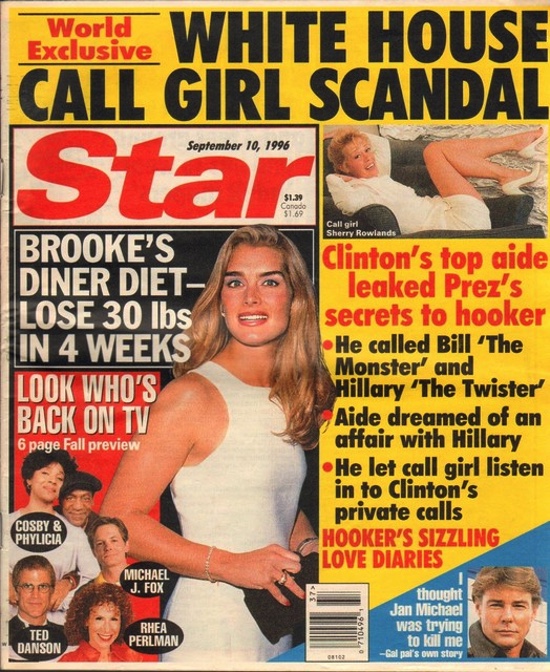

Only three weeks after that, however, rumors began to circulate through space activist and other circles that the story had leaked to the press through another way. The rumor was that Presidential advisor Richard “Dick” Morris had told a high-priced call girl, Sherry Rowlands, about the Mars news and that she in turn had sold the story to the press.

Dick Morris was President Clinton’s chief campaign strategist and perhaps the man more responsible than any other for saving the Clinton campaign from President Clinton himself. Morris was the architect of the strategy of “triangulation”—setting the Democratic president apart both from the Republicans and the Democrats in his own party. The strategy had worked brilliantly, but it had earned Morris the enmity of Democrats as well as Republicans. When news of his relationship with Rowlands leaked to a tabloid on the eve of Clinton’s address to the Democratic National Convention, it was a major scandal. Morris resigned on August 28. He had no real friends in Washington, and virtually no one in either party was sorry to see him go.

|

Rowlands sold her story to the American tabloid newspaper the Star for “less than $50,000,” in the words of the editor who broke the story. Over the next several weeks, she chronicled her encounters with Mr. Morris, which ranged from the sleazily bizarre (Mr. Morris was a foot fetishist) to the ultimate in Washington government weirdness (Morris had read her Hillary Clinton’s speeches and bragged of his importance to the White House). One of her revelations that emerged even before the full story was published was that Morris had told her about the NASA findings.

Rowlands wrote in her diary entry for August 2: “...Then he [Morris] said, ‘I have something very top secret to tell you... This is top military stuff... Only seven people in the entire world know of it.’ He said they found proof of life on Pluto! (SR note: He said Mars, but I was so tired the next morning I wrote Pluto.) It proves there is life out there, so we’ll be sending up more probes and a full-scale discovery program...” [3]

Apparently even before Rowlands’ account was printed in the Star the rumors began circulating, through e-mail messages and over the Internet, that Rowlands and Morris were the source of the leak about the Mars information. But the story does not hold up to scrutiny. There is a clear chain of events leading from the leak of the information to its publication in Space News and the resulting media firestorm.

Rowlands wrote the information in her diary on Sunday, August 3. by which time Space News had already gone to press. She learned of the information the previous evening, while Space News was editorially “closed” and awaiting publication. There was simply no way that the information could have leaked via her.

| The rumors about Morris and Rowlands being the source of the leak persisted, however, and eventually made it into the mainstream media. |

Morris’ bragging that only seven people knew the story was also false. In addition to the nine members of the science team, five senior editors at the journal Science, which was planning on publishing the findings, also knew the story. NASA Administrator Dan Goldin also knew, as did NASA’s Associate Administrator for Space Science, Wes Huntress. Other persons who knew of the findings included the members of the peer review panel, plus a number of people in the NASA Public Affairs Office, and President Clinton and Vice President Gore. These were only those who officially knew, since Leonard David and the editors at Space News also had the story before Morris had told Rowlands about it, although they were not supposed to know about it.

The rumors about Morris and Rowlands being the source of the leak persisted, however, and eventually made it into the mainstream media. In a September 12, 1996, story in the Boston Globe, a reporter wrote, “U.S. scientists openly blamed the White House for a leak of a long-held secret of the discovery of signs of life on Mars... NASA scientist Everett Gibson, an author of the now-famous Mars paper, said he had briefed NASA. ‘We managed to keep it quiet for two years,’ Gibson said in an interview yesterday, ‘Through certain indiscretions, that was leaked.’”

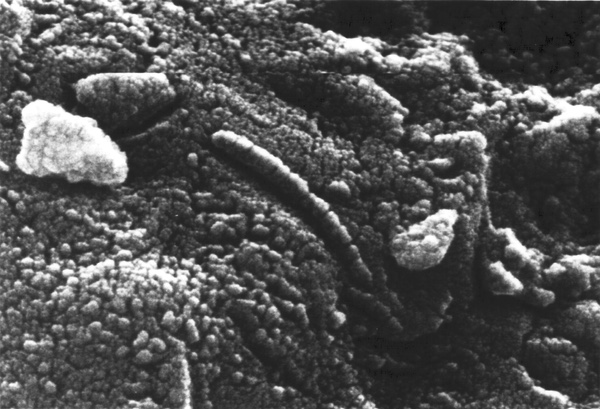

Gibson’s comment that the NASA team had managed to keep the story quiet for two years was not borne out by the facts—or Gibson’s own words. Gibson himself had been talking openly about the team’s work on the meteorite, ALH 84001, as early as spring of 1995. The team had even given a presentation on their early work on the meteorite at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in March 1995. At the time, the team reported that, using a sophisticated laser analysis technique developed by Dr. Richard Zare at Stanford University. they had detected complex organic molecules, called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), inside the meteorite.

All the essentials of the story were present at the March 1995 meeting. including the names of the team members, the name and history of the meteorite in question, and the type of research that the team was conducting. The story was widely reported in the press. particularly in the American Southwest, and Gibson was quoted in many of the articles. Newspapers which carried the story included the Houston Chronicle, the Fresno Bee, the London Times, and the San Francisco Examiner. [4] Science News also ran the story. The articles all noted that the scientists were not claiming to have found evidence of life, but that the findings were consistent with the discovery of life.

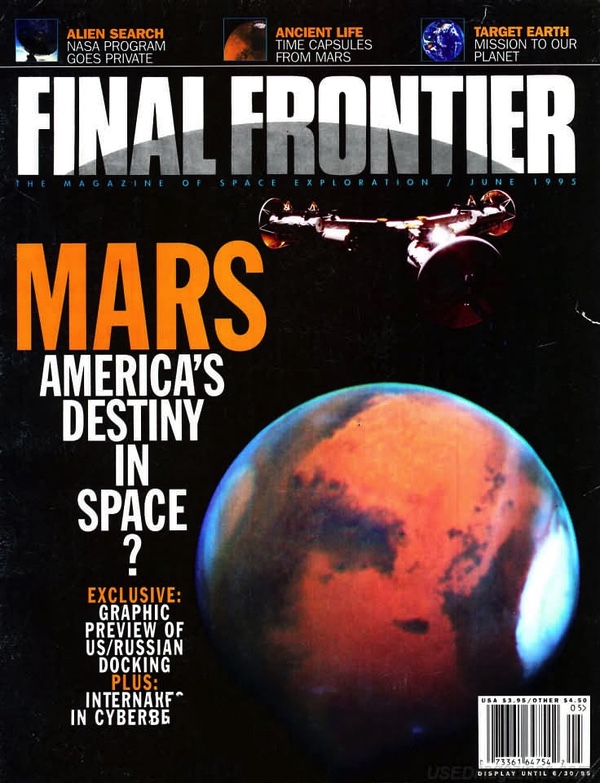

Leonard David had not attended the conference, but he too heard about the new evidence and wrote a story on March 21, 1995, which cited Gibson as a source for information on a new SNC meteorite 4.5 billion years old containing the hydrocarbon. At the time there was no clear evidence of signs of life, but David wrote, “The finding is suggestive that, perhaps, Mars was once a more user-friendly niche for life.” The story even included an anonymous scientist stating, “It opens the door slightly for life on Mars, particularly in the suspected early wet phase of Mars.” [5] David ran the story in the May-June 1995 issue of the space magazine Final Frontier, which he was then editing. The overall issue was devoted to the subject of Mars, but the small story, titled “Time Capsules From Mars,” was tucked away in a sidebar article. [6]

|

Hushing up

According to an interview with members of the research team after the news broke, they had collectively decided to cease speaking to the press late in 1995 when they prepared to submit their paper to peer review. But as late as September 1995, Gibson was still talking to the press about their findings. Another space writer, James Oberg, who also worked at Johnson Space Center, did a television interview with Gibson on KDFW-TV in Dallas that month. The TV spot even included a photo of the limestone circles from the team’s ongoing research. After that, however, press reports on ALH 84001 were virtually nonexistent. When the research team submitted their paper for the journal Science in March 1996, they signed an agreement that they would not divulge any information on their research prior to the publication of the paper, a date which depended entirely on the length of the peer review process.

| After already pitching stories on space tourism and faster-than-light travel earlier in the week. David expected Seitz to say "What’s next, David, a story about Roswell?!" |

The research team’s paper in Science was finally accepted for publication in late July. By this time, the NASA Public Affairs Office at Headquarters in Washington. DC was preparing a press conference to coincide with the release of the article on August 16. They carefully selected speakers for the conference. In addition to all the members of the science team, NASA also chose to include a non-member of the team to serve as a skeptic and counterweight and to add credibility to the proceedings. NASA had done this on a number of previous occasions in order to avoid charges of staging publicity stunts. [7]

The skeptic in this case was Dr. William Schopf. professor of the Department of Earth and Space Sciences at the University of California at Los Angeles. When the Public Affairs Office began asking experts about who would be the most authoritative paleobiologist they could consult, Schopf’s name came up repeatedly. He is considered the foremost expert on the subject.

The story breaks

Leonard David knew that something odd was happening regarding the subject of life on Mars when he attended the Case for Mars VI conference in Boulder, Colorado, in mid-July. Several speakers at the conference jokingly made comments hinting at some discovery pertaining to fossilized life being found on Mars. Clearly a number of people within the Mars scientific community knew about the research. But David did not get the story at that time. He apparently got most of the story soon after Science accepted the paper for publication. However, before he published it, he needed to do some basic fact-checking. One thing he wanted to confirm was that he had the right name of the meteorite. He called another source and asked that person to confirm that ALH 84001 was indeed an SNC meteorite (i.e. one of the dozen that is confirmed to have come from Mars). He did this carefully so as not to indicate to this other source that he was particularly interested in this meteorite. With the information in hand, he sat down to write his brief story that NASA scientists had discovered something interesting. [8]

David had most of the facts, but decided not to reveal all of them out of a concern with protecting his source, so he left some information out of the story. He sent the story to his editor electronically and then talked to him on the phone to convince him to run it. David, who is a correspondent for the paper, as opposed to a staff writer, usually worked with Lon Rains, the paper’s edi¬tor. Rains was on travel and David wasn’t used to dealing with Pat Seitz, Space News’ business editor, and was a little concerned that his article would not be taken seriously. After already pitching stories on space tourism and faster-than-light travel earlier in the week. David expected Seitz to say "What’s next, David, a story about Roswell?!" (As it was, David was working on a story on Roswell—a light-hearted piece for another publication about Roswell. New Mexico, where many UFO-buffs believe a flying sau¬cer crashed in 1947.) Space News is aimed at industry and government circles. not science fiction buffs, and Seitz was concerned that it not be considered to be anything other than a serious publication. [9] Seitz did not reject the story, but wanted to make sure that it was credible and did not damage the reputation of the paper.

After David submitted his article, he went on to other writing assignments. However, the one piece of information that David did not have was the name of the journal where the paper was to be published. He suspected it was probably going to be Science, but was not sure. He did not think that this one piece of information was essential to the story and it was too late to include anyways, but he was still curious.

Space News stopped accepting stories on Friday evenings, “closing” for the week. The paper went to press beginning Saturday afternoon on the 2nd (before Rowlands and Morris had yet to make their regular business transaction). That evening, while attending a party in Washington, David ran into his colleague, Andrew Lawler. Lawler used to be a reporter for Space News and now worked on the editorial board of Science. Although the paper was already being printed, David was still curious about the story and decided to have a little fun. He went up to Lawler during the party when the two were alone in the kitchen and said, “So, what’s the deal with this life on Mars story?” Lawler blanched, telling David that he wasn’t supposed to know about that and thus confirming that the paper was indeed going to run in Science. David then chose to tease him, saying, “Yeah, Andy, Nature has been calling me all day about it...” (Nature is Science’s British-based rival journal.) [10]

Space News is distributed to some important subscribers in Washington as early as late Sunday, with most “hand-deliveries” of the paper not taking place until the early hours of Monday morning. Most other subscribers are at the will of the erratic US Postal Service, although subscribers can also log into a sparse online edition. The first outsiders could read the story over their Monday morning coffee. All day Monday, the 5th of August, the story circulated. NASA Headquarters’ Public Affairs Office took notice of it, but received no calls from enquiring reporters. [11]

By Tuesday morning NASA started getting calls, apparently first from another space reporter by the name of William Harwood. Harwood writes for the New York Times and the Washington Post and also serves as a space consultant for CBS News. Somewhat ironically, Harwood also writes for Space News. He called his editors at CBS and put them onto the story. By Tuesday afternoon the story spread like wildfire through media circles and the phones at NASA Public Affairs were ringing off the hook. Still, no one had anything more than what David had written. Even that had been edited down. The print version of his story was shorter than the on-line version, as a cautious editor had removed all reference to the word “fossils” on Mars.

| The overwhelming consensus was that it did not contain signs of past life on Mars. However, the announcement had a profound impact on space science. |

By Tuesday afternoon, NASA’s Public Affairs Office decided to move up their press conference—originally planned for the middle of August—over a week. Their best laid plans were not all for naught, since they already had all of the preliminary details worked out and their speakers chosen. All they needed to do was to contact them and get them to Washington, DC. They notified the speakers and had them take late night flights from San Francisco and Dallas, both several thousand miles from Washington. Team leader David McKay was on vacation when the story broke. He had a remote telephone pager for just such a contingency, but it did not work and he only learned of the impending press conference when he called his office to see what was happening. He then interrupted his vacation in order to make the sudden trip to NASA Headquarters and the media frenzy that was brewing there.

The news conference itself was a madhouse, with reporters and photographers jostling for position in front of the team members as well as a sample of the Martian meteorite itself, on loan from the Smithsonian Institution. After some initial problems with the audio, however, the conference settled down as the research team carefully made their case and William Schopf expressed his skepticism. Despite the frenetic atmosphere, it managed to be a highly informative session.

Conclusion

Certainly, a majority of the Mars meteorite story was already public long before Leonard David broke the story and it became a media frenzy. Various newspaper and television reporters had gathered most of the facts that were reported later about the perplexing find. They had the name of the meteorite, the names of the research team members, the types of research they were conducting, and the preliminary results of that research. It was not until the research was subjected to the formal peer review process and accepted at a prestigious scientific journal that it finally became “major news.” And it did not leak to the press through the actions of a disgraced toe-sucking presidential advisor.

David himself still finds it surprising that the story garnered the attention that it did. How did obscure and inconclusive research translate into intense attention from around the globe? Was it only because August is traditionally a slow news month? No matter how it happened. the story still has tremendous appeal and has captured the imaginations of many in the world community.

Postscript 2025

The ALH 84001 Martian meteorite data was examined by many other scientists after the publication of the paper in Science. The overwhelming consensus was that it did not contain signs of past life on Mars. However, the announcement had a profound impact on space science. It energized the study of astrobiology, the search for life on other planets and the conditions that make it possible. NASA’s Mars budget increased substantially and the agency began a series of Mars missions with the goal of better characterizing the planet, including the “follow the water” strategy to identify locations on Mars that could have once supported life. That eventually led to the Perseverance Mars rover, which recently found the possible evidence that has current Mars scientists excited. There was also a cultural legacy as well. The announcement led to renewed interest in Mars, and may have contributed to the eventual production of a couple of Mars movies several years later. Bill Clinton’s introduction to the science discovery was re-edited and appeared in the 1997 movie Contact. And the White House advisor with his call-girl became a minor plot point in the 1999 premier episode of the TV series The West Wing. Today’s politics are much more sedate.

Notes

- Interview with Leonard David, Washington, DC, September 1996.

- ”Meteorite Find Incites Speculation on Mars Life,” Space News, 5-11 August, 1996, p. 2.

- Richard Gooding, “My Last Nights With Dick Morris,” Star, September 24, 1996, p. 32.

- Carlos Byars, “Mars Meteorite Contains Carbon Compounds,” Houston Chronicle, 18 March. 1995, p. 34; Keay Davidson, “Forget the Little Green Men, But Life May Have Once Existed On Mars,” San Francisco Examiner, 16 March, 1995, p. A-4; Nick Nuttall, “Martian Meteorite Shows Glimmer of Life On Red Planet,” London Times, 21 March, 1995. Several of the stories were also carried by other newspapers as well. The San Francisco Examiner story, for instance, appeared in both the Fresno Bee and The Plain Dealer.

- Memo, Leonard David to Geoff Briggs, “Mars Research,” 21 March, 1995, provided by David to author.

- ”Time Capsules From Mars,” Final Frontier, May-June 1995, p.

- Telephone interview with Don Savage, NASA Public Affairs, September 1996.

- Interview with Leonard David.

- Telephone interview with Patrick Seitz, Space News, September 1996.

- Interview with Leonard David.

- Telephone interview with Don Savage.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.