Gemini’s wing and a prayer (part 2): Parachutes, paragliders, and more crashes in the desertby Dwayne A. Day

|

Francis Rogallo conceived of his wing design in the late 1950s. Here he is with a wind tunnel model in 1959. The advantage of the soft wing was that it was lightweight and could be folded up. NASA conducted many tests of several wing designs in the early 1960s. (credit: NASA) |

The desert tests of the Paresev were not the only activities conducted in what became an extensive development program. In March 1962, test pilot Milt Thompson went to North American Aviation in Downey, California, and flew a Gemini parawing simulator. He maintained close ties with the other aspects of the research project.[1]

| MSC engineers realized that an accident that destroyed one of the boilerplates could have a significant impact on the test program. |

NASA also started a new series of wind tunnel tests. On May 23, 1962, the Ames Research Center tested a half-scale paraglider wing in one of the center’s wind tunnels. Further wind tunnel tests demonstrated all phases of paraglider operation, from deployment all the way down to landing. During some later tests the wing ripped. But the tests were finished by July 25. [2] At the same time, North American built two boilerplate capsules for paraglider drop tests from aircraft. One was a scale mock-up known as a Half Scale Test Vehicle, or HSTV, and the other was known as the Full Scale Test Vehicle, or FSTV. The boilerplates did not have any of the internal systems of an actual spacecraft and were primarily intended to simulate the shape and weight of Gemini and nothing more.

Half Scale Test Vehicles were developed for testing the wings. Two of the HSTVs were destroyed in crashes. (credit: NASA) |

Parachute tests

The boilerplates were far simpler than an actual spacecraft but were expensive for test vehicles. MSC engineers realized that an accident that destroyed one of the boilerplates could have a significant impact on the test program. They ordered North American to develop an emergency parachute system that would deploy if the paraglider failed. This decision had a significant impact on the testing schedule, because now North American had to test and prove the emergency parachute system before starting paraglider tests. North American subcontracted the emergency parachute system to Northrop Corporation’s Radioplane Division. [3]

On May 24, 1962, North American dropped the Half Scale Test Vehicle from an aircraft in the first test of the emergency parachute system. It was equipped with a single parachute and the test was successful. Another test on June 20 also succeeded. On June 26, the parachute failed and the boilerplate was damaged and had to be returned to North American’s factory in California for repairs.

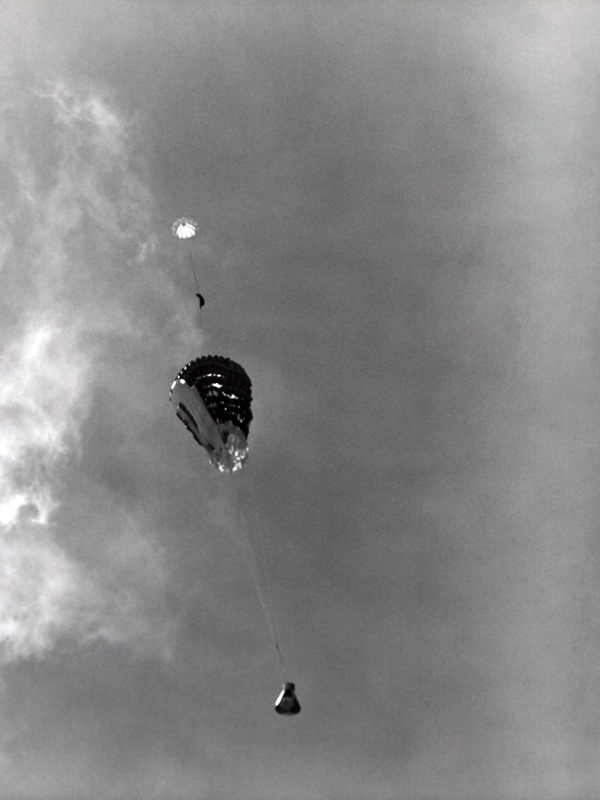

NASA required that the boilerplate test vehicles be equipped with emergency parachutes in event that the paraglider wing did not deploy. Here the parachute is being tested in 1963. The parachute system had to be tested for both half-scale and full-scale vehicles, and suffered some problems. (credit: NASA) |

On July 10, North American conducted another test and the parachute failed again. This forced another delay in the testing until the flaws were corrected and the test vehicle repaired. On September 4, the Half Scale Test Vehicle was dropped again and the parachute system operated successfully. NASA declared the parachute system qualified. [4]

As the tests with the Half Scale Test Vehicle progressed, North American began testing the Full Scale Test Vehicle, which was equipped with three emergency parachutes instead of one. On August 2, they successfully conducted the first drop test. On August 21, they conducted the second, but lost a parachute after deployment. During the next test on September 7, two of the three parachutes were lost and the test model hit the ground hard and was slightly damaged. The next test was delayed until November 15, and ended badly when all three parachutes failed and the vehicle crashed. NASA ordered McDonnell, which was building the Gemini, to supply North American with a spare boilerplate capsule to resume testing.

NASA used many methods to test various wing configurations, including towing it behind a truck in the desert. (credit: NASA) |

Paraglider failures, parachute failure

Meanwhile, North American was having other problems. The contractor began tow tests with the Half Scale Test Vehicle at the Flight Research Center. The paraglider was deployed and inflated on the ground and then the capsule was towed into the air by an Army helicopter. Once it reached the right altitude, the cable would be released and the capsule would make a radio-controlled descent. [5]

On August 14, 1962, North American engineers conducted the first test. The wing was folded during the tow to altitude but refused to unfold in flight. Three days later they tried again, but the wing released too soon. On August 23, they tried yet again, but the vehicle descended too fast and was slightly damaged on landing. The next test took place on September 17, but the tow-line failed to release and the helicopter had to return to base.

A Rogallo Wing struts inflated with nitrogen is being connected to the Paresev vehicle in 1963. Note the lifting body aircraft in the background. The 1960s was a period of intensive aeronautics testing by NASA. (credit: NASA) |

Several more delays occurred, at which point MSC halted the testing until the problems were fixed. Tests resumed on October 23, and this time the paraglider successfully lowered the vehicle to the ground. [6] But a major milestone remained: deploying the wing in flight. Still more problems delayed the test until December 10. An HSTV was carried up to altitude by a helicopter and dropped. The paraglider was folded inside its storage can. But the drogue parachute did not operate properly and the paraglider did not properly deploy. The test controllers jettisoned the paraglider and deployed the emergency parachute, which operated properly. [7]

Another attempt was made on January 8, 1963. But the wing deployed too late and tore. Ground controllers commanded the emergency parachute to deploy, but it did not and the HSTV crashed. [8]

The Half Scale Test Vehicle was carried aloft underneath a heavy-lift CH-37 Mojave helicopter.(credit: NASA) |

Put up, or shut up

Gemini was scheduled to begin uncrewed orbital flights in 1964. By this time the Gemini program was experiencing cost overruns that forced the program managers to make some hard choices. The Office of Manned Spaceflight at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC, wanted a successful deployment of the paraglider before it would approve more money for the program. But the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston wanted to award a contract for Phase III of the program. Washington won the argument.

| In retrospect, North American’s problems with the emergency parachute system should have been a clear warning sign that the company was experiencing quality control and workmanship problems. |

On March 11, 1963, a helicopter took the second HSTV aloft and dropped it. But once again the storage can did not separate, the paraglider could not be deployed or even jettisoned. The radio command for the emergency parachute was also ineffective and the capsule fell to the ground. Now North American had destroyed both Half Scale Test Vehicles.

In retrospect, North American’s problems with the emergency parachute system should have been a clear warning sign that the company was experiencing quality control and workmanship problems. Parachutes are admittedly more complex than they seem, and their performance is hard to model or predict mathematically. However, they are still relatively simple devices and North American’s problems with getting the parachutes to deploy indicated not so much design problems as a failure to perform the kinds of checks and oversight required to make sure that even simple operations happen the way that they are supposed to happen.

The progression of the paraglider research also was a bad sign as well. All new technologies experience difficulties in development. But a well-run development program will not repeat the same mistakes and the same failures as engineers systematically solve the problems. The persistence of even simple failures with the paraglider development indicated that there were bigger problems as well.

The paraglider testing continued, but the pressure was mounting to make it work, or it would be removed from the Gemini program.

Next: Boilerplates and Kabongs.

A 1963 test of a Half Scale Test Vehicle under an inflated paraglider wing resulted in some damage.(credit: NASA) |

- M.O. Thompson and Curtis Peebles, Flying Without Wings, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1999, p.19.

- Ibid., p.47.

- On the Shoulders of Titans, p.92; Project Gemini: A Chronology, p.30.

- On the Shoulders of Titans, pp.98-99.

- Ibid., p.99; Project Gemini: A Chronology, p.56.

- On the Shoulders of Titans, p.123.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.; Project Gemini: A Chronology, p.66.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.