Unleashing hell: the R-16 ICBMby Dwayne A. Day and Harry Stranger

|

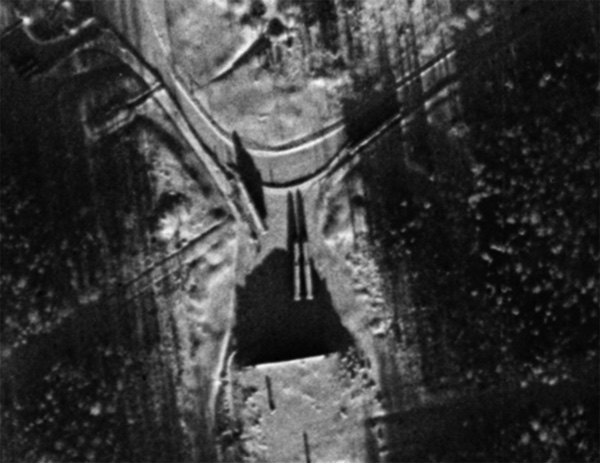

The R-16 ICBM (which NATO designated the SS-7) was launched from external launch pads as well as underground silos. The missiles could carry five- to six-megaton thermonuclear weapons. These satellite photos represented an intelligence coup for the US intelligence community. (credit: Harry Stranger) |

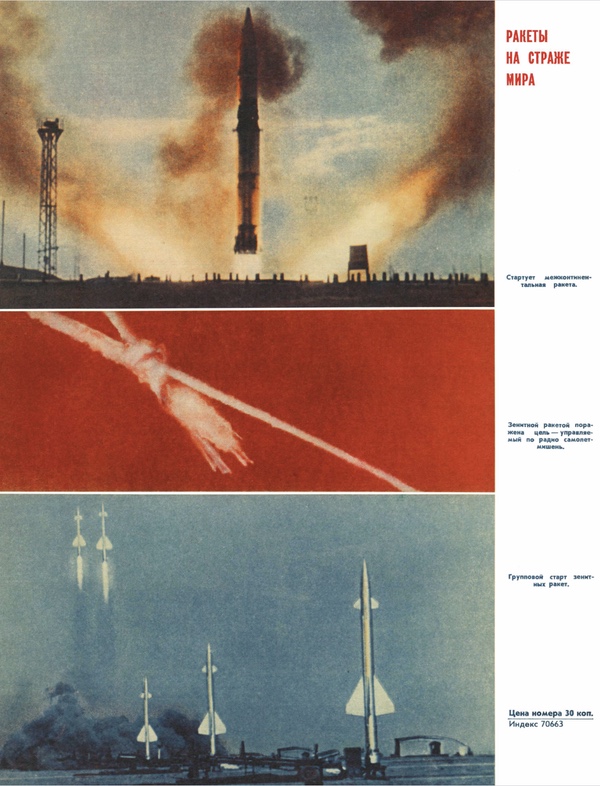

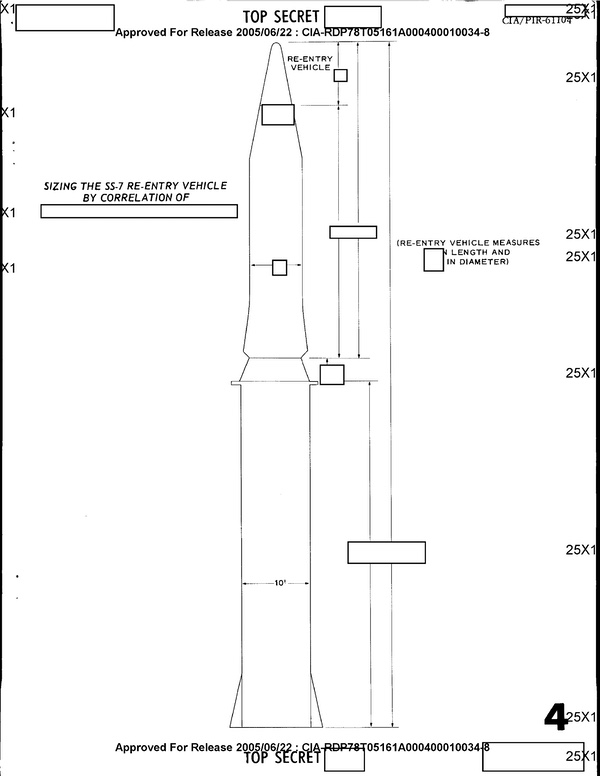

As the report indicated, the satellite photos were the second intelligence coup on the SS-7 in only a few months. In June 1965, the Soviet magazine “Ogonek” published a photo of an SS-7 launch on the back cover. The Soviets had never released photos of their ICBMs. When Ogonek published the photo, the CIA correlated the ground photograph with satellite photography taken by reconnaissance satellites. “It is believed that the view shown in ‘Ogonek’ was taken at Launch Area D-1, Tyuratam Missile Test Center,” a CIA report stated. The CIA noted that the photograph showed a W-shaped exhaust, which indicated ports on either side of the launch silo, and also speculated that studs on the top of the missile first stage indicated that it rode out of the silo on rails.

Those two developments provided much better info on the SS-7 than what the US intelligence community previously had. What the CIA referred to as Tyuratam was known to the Soviet Union as Baikonur. Baikonur was also the location where a SS-7 launch had gone terribly wrong several years earlier, dealing a major setback to the Soviet ballistic missile program.

In summer 1965, the Soviet magazine Ogonek published a photo (top) on the back cover showing the launch of an SS-7/R-16 ICBM. This was the first time a photo of the missile appeared in any Soviet publication, and the CIA used it to estimate the missile’s size. (credit: Ogonek via Asif Siddiqi) |

Saddler

The SS-7, known as the “Saddler” to NATO and R-16 to the Soviet military, first entered service in 1961. It was the first practical Soviet ICBM, with storable propellants. It followed the SS-6, known as the R-7 “Semyorka” to the Soviet military. The R-7 used liquid oxygen and kerosene, meaning that it had to be fueled before launch because the oxygen could not be kept in the missile. Fueling was a slow process and made it vulnerable to attack. The R-7 was retired from its ICBM role but went on to a long and successful career as a space launch vehicle. It was used to launch both Sputnik and later Yuri Gagarin into space. The R-7’s descendant, known as the Soyuz rocket, is still in use today.

The newer SS-7/R-16 used hypergolic propellants, unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH) and red fuming nitric acid (RFNA) as oxidizer. When mixed, the substances immediately ignite. They can be stored. But they’re also corrosive, meaning that they eat away at seals in pumps and valves. The R-16 could stay fueled for a few days at a time. This wasn’t ideal, but it was superior to the R-7, and the missiles could be fueled and stay on alert for several days in event of crisis. However, if there was an explosion or leak, RFNA could produce what American missileers referred to as a “big fuming red cloud,” although they didn’t use the word “fuming.” If you saw a BFRC, you were supposed to run for your life.

CIA drawing of the SS-7/R-16 ICBM with measurements deleted. This drawing and the measurements were derived from both the 1965 magazine photo and satellite photos taken in early 1966. (credit: CIA) |

The R-16 was first deployed to Yurya in 1961. The missile was initially deployed to hangars and could be rolled out, erected, fueled, and prepared for launch. While outside, they were vulnerable to attack, and their inability to be permanently fueled also presented problems. It was after being rolled out of a hangar that the American GAMBIT satellite photographed them on a surprisingly clear winter’s day.

The R-16 had an 11,000-kilometer range and was equipped with a five- to six-megaton thermonuclear warhead. With a smaller three-megaton warhead the missile’s range increased to 13,000 kilometers. Like all early Soviet ICBMs, it was not very accurate, with a circular error probable (CEP) of 2.7 kilometers, meaning that 50% of the missiles fired would fall outside of a circle with a 2.7 kilometer radius. The large warhead compensated for the poor accuracy.

Starting in 1963, some R-16 missiles were based in silos. However, the silos had to be located relatively close together so that the missiles could use the same fueling system, making them vulnerable to a single US missile.

In November 1960, a CORONA reconnaissance satellite photographed the sprawling missile and rocket test center at Baikonur (then referred to as Tyuratam by the CIA), including the damaged SS-7/R-16 pad that was the site of the October 24 explosion. |

The Nedelin disaster

On October 24, 1960, at Baikonur, a prototype R-16 missile exploded on the pad while dozens of workers were around it. Many were killed. The exact number is unknown but is believed to be 60 to 150. Chief Marshal of Artillery Mitrofan Ivanovich Nedelin, who was the head of the R-16 development program, was killed in the explosion, which was then commonly referred to as the “Nedelin catastrophe.” Another fatal accident involving a different missile occurred on October 24, 1963, and that date is now referred to as the “Black Day” at Baikonur. As a result, Russia no longer launches missiles or rockets at Baikonur on October 24.

The aftermath of the October 1960 explosion. The number of people killed in the explosion is unknown because of the devastation, but estimates are that 60 to 150 people were killed. The day became notorious within the Soviet space and rocket program. (source: Russian documentary footage) |

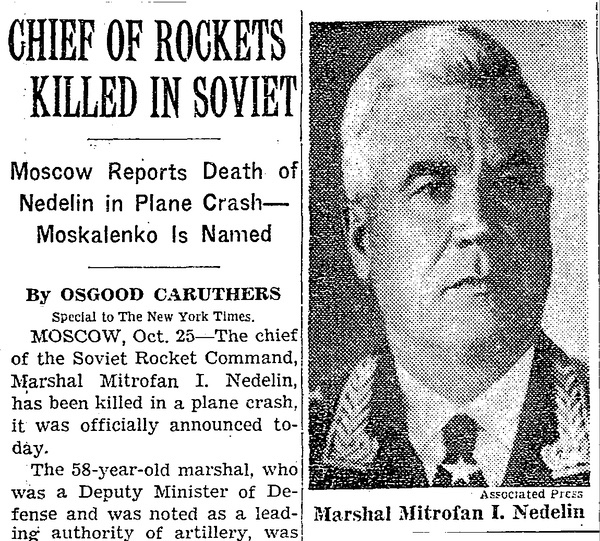

The Soviet Union announced that Nedelin had been killed in a plane crash a day after his death, and this was reported in The New York Times on October 26. The deaths of two other senior officials were also announced by the Soviets in the weeks after the explosion, without details. The rocket explosion was first reported by an Italian news agency in December 1960, listing the names of three people, including Nedelin, who were killed in the explosion. For decades Western independent experts speculated about the accident. Some, such as Jim Oberg in his book Red Star in Orbit, noted that the explosion happened during a Mars launch window and theorized that it was a Mars mission that had gone bad when an upper stage had fired while the fueled rocket was on the pad.

The day after the explosion, the Soviet Union announced that the head of their rocket forces had been killed in a plane crash. Several months later, his and several other deaths were linked to the October 1960 explosion. It was not until 1989 that more details were publicly revealed. (credit: NY Times) |

A few weeks after the explosion, an American CORONA reconnaissance satellite photographed Baikonur—the first reconnaissance photos of the sprawling test site. An astute photo-interpreter might have noted the disturbed ground near the R-16’s launch site, an indication that something had recently exploded there.

The CIA had figured out that it was an SS-7/R-16 missile that blew up in 1960. It is unclear exactly when the CIA connected the Baikonur explosion to the R-16, but an October 1965 CIA report clearly connected the dots (see “A mystery, wrapped in an enigma, surrounding an explosion: US intelligence collection and the 1960 Nedelin disaster,” The Space Review, November 14, 2022.)

On October 24, 1960, an R-16 ICBM test missile exploded on its pad at Baikonur, killing dozens of technicians and military officials nearby, including several senior missile program officers. (source: Russian documentary footage) |

Coincidentally, in 1989 it was Ogonek magazine that first revealed details of the Nedelin catastrophe, including that it was an R-16 ICBM and not a Mars rocket that had exploded in 1960. In the 1990s, a Russian source also released horrific film footage of men running away from the burning conflagration, some of them apparently on fire.

The deaths of many people working on the R-16 caused delays in the program. The missile’s first flight finally occurred on February 2, 1961, and it entered service on November 1, 1961. By 1965, when Ogonek published the missile launch photo, the Soviet Union had deployed 202 of the missiles. The R-16 served until 1976 when it was withdrawn from service.

Notes

Central Intelligence Agency, Photographic Intelligence Report, “Construction Status of Soviet Single Silo ICBM Sites,” and “Mensural Data on Soviet SS-7 ICBM,” March 1966. CIA-RDP78T05161A0004000100034-8

Central Intelligence Agency, Photographic Intelligence Report, “ICBM Silo Launch,” September 1965. CIA-RDP78T05439A000500310060-0

Bart Hendrickx, “Building a Rocket Base in the Taiga: The Early Years of the Plesetsk Launch Site (1955-1969) – Part 1, Space Chronicle: JBIS, Vol. 65, Supplemental 2, 2012.

Bart Hendrickx, “Building a Rocket Base in the Taiga: The Early Years of the Plesetsk Launch Site (1955-1969) – Part 2, Space Chronicle: JBIS, Vol. 66, Supplemental 1, 2013.

Osgood Caruthers, “Chief of Rockets Killed in Soviet,” The New York Times, October 26, 1960, p. 22.

“Rocket Cited in Deaths,” The New York Times, December 10, 1960, p. 6.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.