New Zealand looks for its place in the global space industryby Jeff Foust

|

| “As we’ve seen from the protestors outside today, some people have different perspectives on how aerospace technology is used,” said Mark Rocket, president of Aerospace New Zealand. |

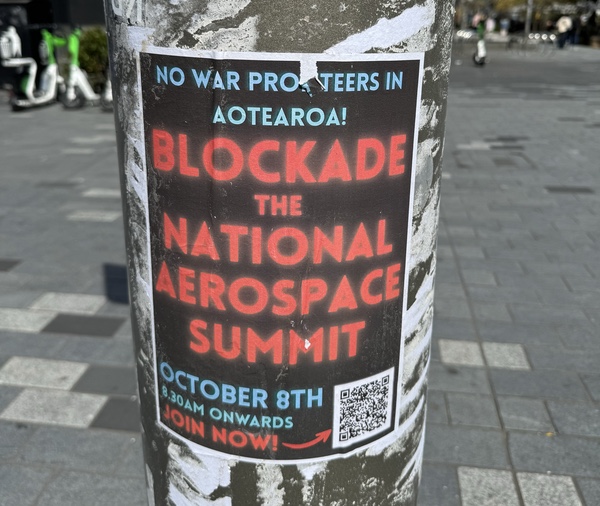

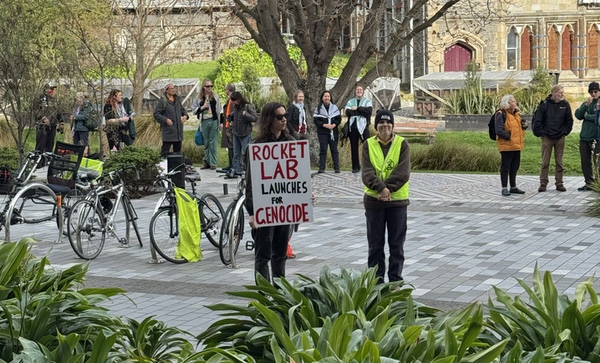

The summit was a two-day event at the city’s convention center, although the signs indicated the blockade was intended for only the second day, devoted to plenary speeches and panels. There were a few dozen protestors outside the center on the first day, October 7, some waving Palestinian flags and linking New Zealand aerospace capabilities to Israel’s conflict in Gaza. Others were more generally concerned about the militarization of space that they believed could draw the country into some future conflict.

Some protestors focused their attention on the country’s most prominent space company. “Rocket Lab Launches for Genocide,” one sign stated. “Peter Beck Makes NZ a Target,” read another.

On the second day, there were more protestors outside the center and more than a dozen forming a “blockade” in front of the main door, seated with linked arms. But the entrance was not blocked: people could simply walk around the blockade to get inside. The only drama came when several protestors raced for the entrance, either to join the blockade or to get inside (one tried opening a side door, only to find it locked); they were subdued by police and security.

Top: flyers posted around the center of Christchurch calling for a “blockade” of the conference. Bottom: protestors outside the convention center. (credit: J. Foust) |

Inside the center, the protestors were out of sight and, largely, out of mind, with only a few passing references to them.

“As we’ve seen from the protestors outside today, some people have different perspectives on how aerospace technology is used,” said Mark Rocket, president of Aerospace New Zealand, in remarks opening the conference, arguing that most companies in the country focused on commercial or civil applications. “Some of our industry does work with the defense sector, but we have stringent laws that these New Zealand-based companies are in line with government policy.”

The event leaned into celebrating the country’s aerospace industry. Speakers were greeted with walkup music played by an onstage DJ: a woman in a silver bodysuit festooned with mirrors and wearing a mirrored helmet. It was an homage either to Daft Punk or to Humanity Star, the mirrored satellite placed in orbit by the first successful Electron launch in 2018.

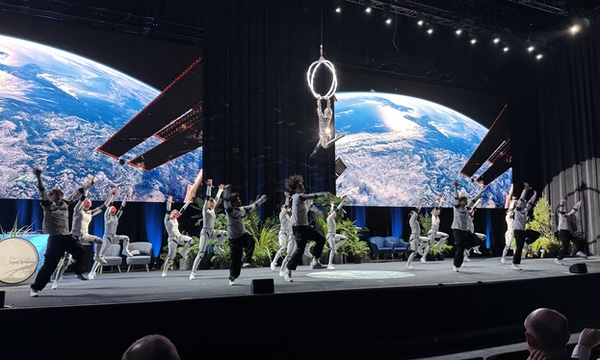

Later, the emcee encouraged people to return to the auditorium promptly after lunch for a special feature, one not listed on the day’s agenda. Those who did so were greeted to a performance by dozens of dancers, most wearing Star Wars-themed costumes, while videos of accomplishments of New Zealand aerospace companies played in the background. Several of the dancers, dressed as stormtroopers, started breakdancing at one point, removing their helmets to perform their moves. The audience cheered, even if people were still puzzled about what they saw and what it had to do with the country’s aerospace industry.

Top: the conference has an on-stage DJ playing walkup music for speakers. BBottom: the post-lunch dance performance, before the breakdancing stormtroopers appeared. (credit: J. Foust) |

Innovating versus scaling

Amid the entertainment inside and the protestors outside, one central question remained: what is the place of New Zealand’s space industry in a global space economy increasingly dominated by the United States, China, and a few other nations?

It is a growing industry. Space companies contribute about NZ$2.5 billion (US$1.45 billion) annually to the country’s economy and the industry is growing 8.9% per year for the last five years, noted Gerard Dale, a partner at law firm Dentons New Zealand, during one panel discussion at the conference.

“To put that into context, in the last five years the New Zealand economy has grown by about 9%,” he said. “You guys do that every year.”

| “What if New Zealand decided to go after a piece of that $2.3 trillion market—and not just a little piece, but a decent piece, say, something like 10%?” said Beck. |

It is also growing faster than the global space economy. The 53% growth in the country’s space industry in the last five years is greater the 40% growth reported globally in the same timeframe. “It’s not that I’m competitive,” Judith Collins, New Zealand’s space minister, said in a keynote at the conference, “but it’s really good when we’re beating everyone else.”

Dominating that industry, of course, is Rocket Lab. In a video keynote at the conference, Peter Beck, founder and CEO, said there was an opportunity for New Zealand to take a bigger stake in a space industry that he projected to be worth $2.3 trillion at some unspecified future date.

“There has never been a better time to think big beyond our borders,” he said. “What if New Zealand decided to go after a piece of that $2.3 trillion market—and not just a little piece, but a decent piece, say, something like 10%? That should be achievable, and that kind of productivity and capital injection into the country could mean incredible things for growth, innovation, and new technology.”

That meant New Zealand companies needed to think big. “Show me the path to becoming a billion-dollar company,” he said. “I’m only interested in things that have the potential to be big.”

Rocket Lab has become big, at least in terms of stock market valuation. While the company has yet to turn a profit, its share price has soared on the Nasdaq in the last year from about $10 a share to, as of market close on October 20, $67.35. That gives the company a market capitalization of more than $30 billion.

“If Rocket Lab was a New Zealand company, it would be the most valuable one in the country,” said one attendee on the sidelines of the conference.

But that’s the catch. Rocket Lab was founded in New Zealand and still has major operations in the country. A factory in Auckland produces Electron rockets—more than half a dozen were in various stages of production during a visit just after the conference—that are launched from its Launch Complex 1 on New Zealand’s Mahia Peninsula.

However, the company moved its headquarters several years ago to the United States, helping it win US government business. Most of its new projects, such as its work building satellites and components, as well as its Neutron rocket, are taking place in the US, not New Zealand.

That was a theme that emerged from conference discussions: New Zealand may be a good place to start a space company, but scaling it up there can be difficult.

“What is New Zealand good at? We’re good at innovation. We’re good at coming up with innovative products in the world. But we don’t have the resources,” said Imogene Lomax, a manager with New Zealand Trade and Enterprise. Companies, she said, often find they need to have “capability as close to your customers as you can.”

Raising money can be difficult for companies as well. “If you need more than $5 million you need to be running a global process,” said Angus Blair, general partner at Outset Ventures, a venture capital fund based in the country, citing limited investment resources within New Zealand.

That was the experience of Zenno Astronautics, a company based in New Zealand developing superconducting magnets for space applications, starting with attitude control systems. The company has raised nearly NZ$30 million (US$17 million) beginning in New Zealand but later branching out to investors in Japan and the United States.

“On of the reasons that we invested in Zenno is because of its state-of-the-art innovative technology really fits into the Japanese space industry,” said Ryo Kotera of All Nippon Airways, which invested in Zenno as part of its efforts to diversify its business. “Japanese satellite customers are facing problems with attitude control systems, and its product can solve this problem.”

| “If we needed to fill Neutron with liquid oxygen, we would only be able to do so halfway with all of the liquid oxygen in New Zealand,” Lloyd said. |

Max Arshavsky, co-founder and CEO of Zenno, acknowledged that focusing on components alone would not provide the returns that VC investors are looking for. “Our intention was always to start with a very narrow niche in an existing market, and then to evolve that product further, which will then create new markets and new capabilities,” he said.

He declined to elaborate on those new capabilities but did not lack in ambition. A company whose valuation exceeds $1 billion is often called a “unicorn” because such companies were once rare. “We are building a hyper-unicorn,” he declared.

Judith Collins, the New Zealand government’s space minister, gives a keynote at the conference. (credit: J. Foust) |

Capitalizing on strengths

Companies at the conference mentioned other challenges in scaling up a space business in New Zealand. They included educating a trained workforce as well as basic infrastructure.

Benjamin Lloyd, senior director for legal and global risk manager at Rocket Lab, said one reason the company is not launching Neutron from New Zealand is availability of liquid oxygen. “If we needed to fill Neutron with liquid oxygen, we would only be able to do so halfway with all of the liquid oxygen in New Zealand,” he said.

The country, though, has its strengths. One frequently cited at the conference was open access to airspace and a regulatory system that makes it easy for experimental vehicles to get approvals to use it. That has primarily benefitted companies in advanced aviation, such as developers of drones and electric vertical-takeoff-and-landing aircraft.

It has also helped Dawn Aerospace. The company is developing the Aurora uncrewed spaceplane, flying it to altitudes of 25 kilometers and speeds of Mach 1.1 from New Zealand. A new version of the vehicle in development will be able to go to 100 kilometers and faster than Mach 3.

The company started sales of that vehicle earlier this year, with the Oklahoma Space Industry Development Authority ordering one in June to fly from the state’s spaceport, a former Air Force base, starting in 2027.

The company has benefitted from New Zealand’s regulatory environment. “We could not have achieved the things that we have if we didn’t have a regulator who wanted to find a way to say yes,” said James Powell, co-founder and chief spaceplane engineer at Dawn Aerospace. “It doesn’t mean that this is all easy and it doesn’t mean this is all quick, but there is open-mindedness and there is an attitude of, ‘Let’s try to find a way.’”

Aurora is a first step towards long-term ambitions for orbital vehicles that offer the same level of reusability as aircraft. “It seems to us that there’s a pretty clear path here that we can start with an aircraft. We can have the full reusability from day one, and we can start to leverage this massive, globally deployed market of aircraft,” said Dawn Aerospace CEO Stefan Powell in a conference keynote, “and we can start plowing our way towards that Holy Grail.”

In the process, “we can also cut straight through this market of supersonic and hypersonic research,” he said. “We can build real businesses there. This doesn't have to be a massive chasm we have to cross as a company.”

| “We could not have achieved the things that we have if we didn’t have a regulator who wanted to find a way to say yes,” said Dawn Aerospace’s James Powell. |

Some in the country’s space industry are looking to the government for increased investment to address some of the challenges they face. In her keynote, Collins, who also serves as New Zealand’s defense minister, suggested the country would spend more in national security space capabilities. She cited a strategy the country released in April that called for increasing defense spending by NZ$9 billion (US$5.2 billion) over the next four years, including in space systems.

More details will come in a separate defense space sector plan to be released in the next six months, she said. “It will set out how we will grow and sustain a space industry that supports defense capability and contributes to innovation and export opportunities,” she said.

That risked putting it at odds with the protestors outside the conference, but she dismissed those concerns in an interview after her speech. “The people outside today are the usual suspects who turn up every single thing we ever do,” she said, saying there was “huge public support” in general for the country’s space activities.

The open airspace and regulatory environment were a particular strength for the industry in New Zealand, she said. “We don't have any near neighbors. We have an environment where we can have the high cadence of launches,” she said. “We also have regulatory system that is agile as well as safe.”

“If I take someone like Peter Beck of Rocket Lab, a home-grown New Zealand engineer now responsible essentially for us being the third in the world for successful vertical launches, I reckon we have a place” in the global space industry, she concluded.

“New Zealand could be a leader in aerospace,” Lloyd said. “If we put government behind it, we put industry behind it, if we put our collective minds behind it, that could be New Zealand’s next big industry.” No breakdancing stormtroopers required.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.