Spinning, spinning, spinning to Marsby Dwayne A. Day

|

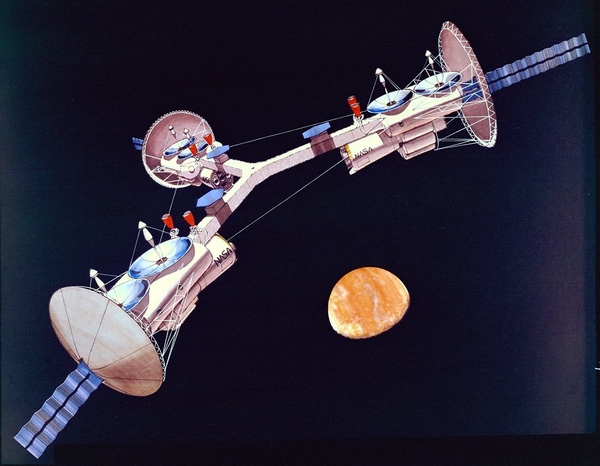

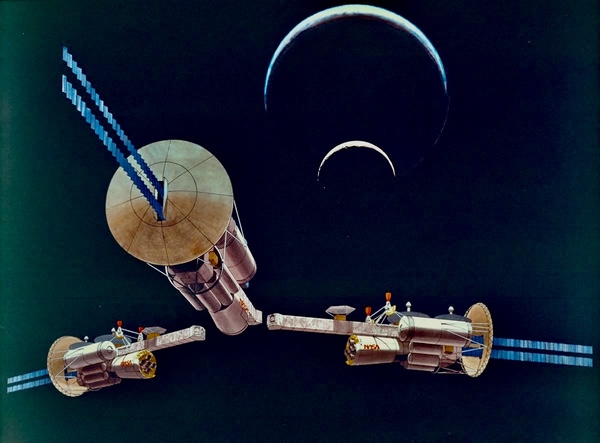

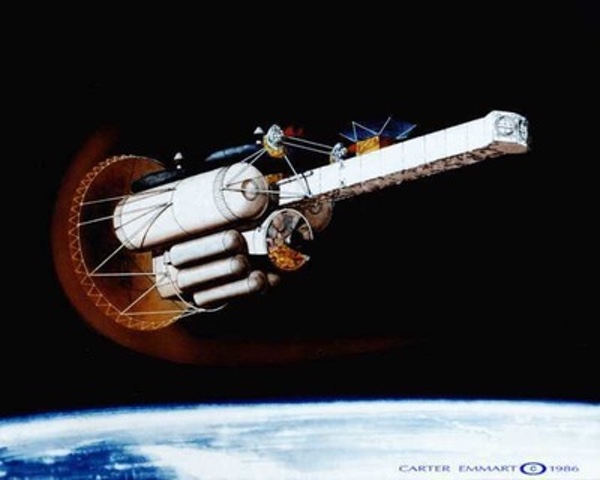

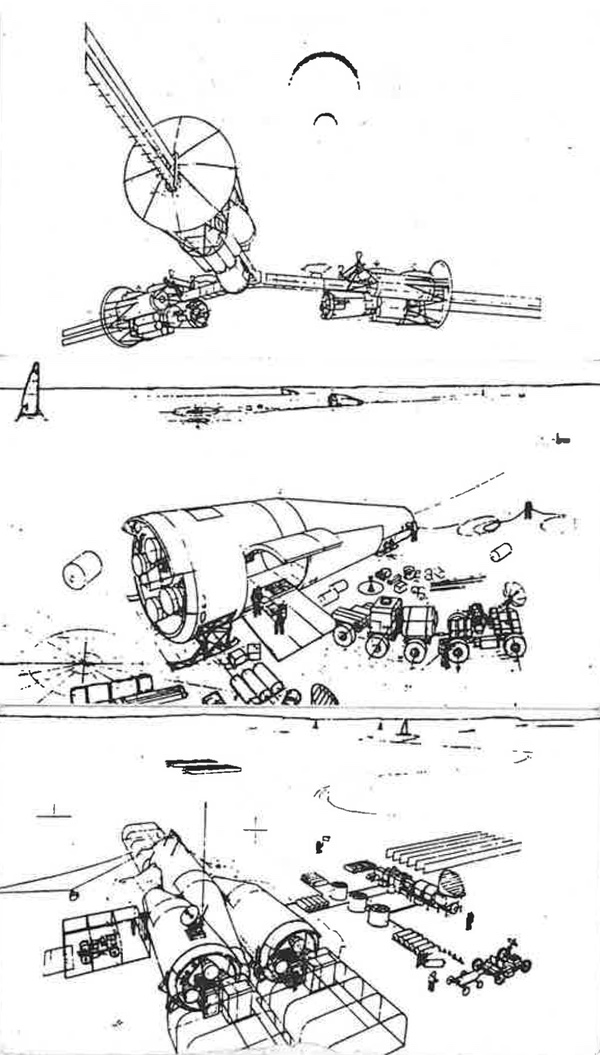

The Mars cycler spacecraft would be assembled in Earth orbit at a space station. The three Habitat vehicles would then head to Mars. (credit: Carter Emmart) |

Origins of the Case for Mars Conference

Two weeks after the launch of the Space Shuttle Columbia in 1981 on its first mission, a group of Mars enthusiasts met for a conference. The organizer was Christopher McKay, then an astro-geophysics Ph.D. candidate at the University of Colorado at Boulder. They based their conference on NASA’s 1976 study “The Habitability of Mars.”

The University of Colorado Space Interest Group had started planning a year earlier, in spring 1980, and focused on Mars because Mars research had dried up after the Viking missions. Benton Clark had written a paper in 1978 called “The Case for Mars,” which provided the name for the conference. The 1981 conference consisted of around 300 engineers, scientists, and other enthusiasts. This was at a time when NASA had no active projects underway to explore the Red Planet. The Viking missions had created a lot of excitement about the possibility of life on Mars, and when it was not discovered, public attention and government funding went elsewhere. Journalist Leonard David coined the term “Mars Underground” in a November 1979 article for Future Life magazine, referring to them as “a small clique of maverick space enthusiasts, both in and out of government,” adding that they were a “the modest and secretive clan.” The Case for Mars conference was their debut party.

Several concepts for human exploration of Mars were presented at the 1981 conference, including a proposal for a human mission to the Mars moons Phobos and Deimos that would not land on the planet. But many of the attendees had greater ambitions. They wanted humans to walk on Mars. To live off the land. And to stay.

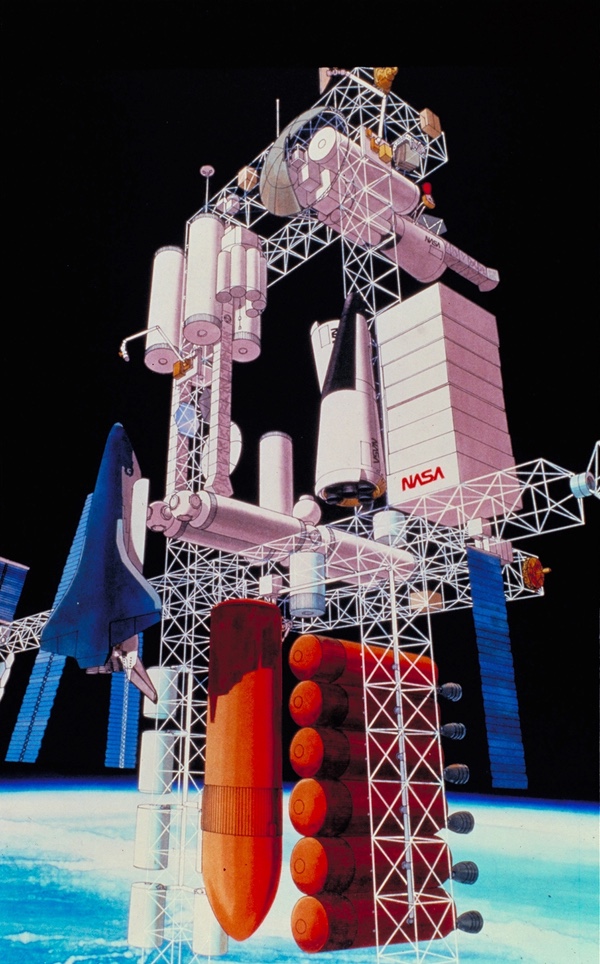

The Habitat vehicles would be boosted to Mars with propulsion stages. These would be jettisoned after use. (credit: Carter Emmart) |

Case for Mars II Mission Workshop

In July 1984, the organizers held the Case for Mars II conference. This included a workshop to develop a “permanent Mars research base using year 2000 technology” as a “precursor to eventual colonization.” The participants had a goal to develop a concept that was not only a first human mission to Mars, but a continuing human presence, including the rotation of crews on the surface. This was admittedly bold and unrealistic, because any human exploration of Mars would start with a single mission rather than a continuous set of missions. But they picked “a Mars base as the much-needed long-term focus for the space program,” according to a summary written by James French, and chose a permanent base “rather than the more conventional concept of a series of individual missions to different sites, because the permanent base offers much greater scientific return plus greater crew safety and the potential for growth into a true colony.” A goal was to strive for self-sufficiency and autonomy from Earth, using Martian resources whenever possible. In April 1986, JPL funded a lengthy report on the workshop results. French presented his summary a year later.

The three vehicles would connect on the way to Mars and start spinning to produce the equivalent of Mars gravity. (credit: Carter Emmart) |

Mission concept

The participants assumed that robotic precursor missions would be necessary before any human missions. These would be required to provide high resolution imagery of possible landing sites as well as information on resources such as volatiles (i.e. water) and scientifically interesting locations. The humans would travel to Mars in a “Mars cycler.”

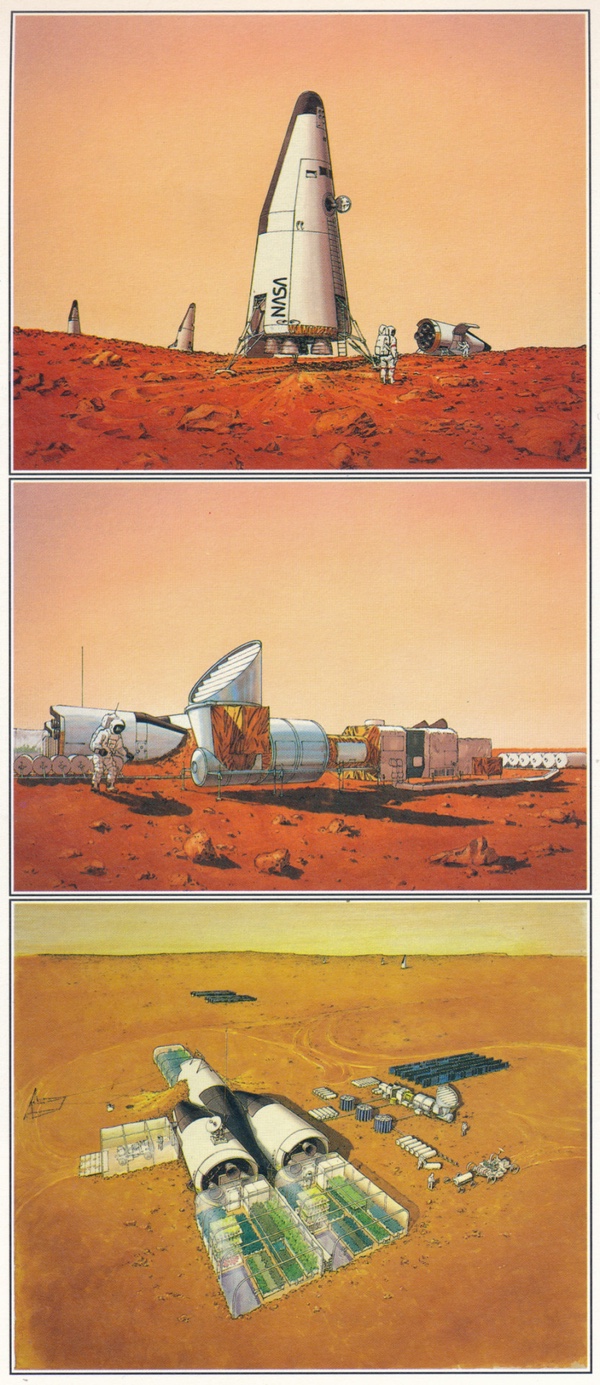

The Mars cycler would use three spacecraft assembled at a space station in Earth orbit. The spacecraft would launch to Mars individually and then join up. They would then start rotating to provide artificial gravity. The transit time to Mars would take six months. The Earth return leg would last 20 to 30 months. The crews would spend two years on Mars. New crews would leave for Mars every 26 months.

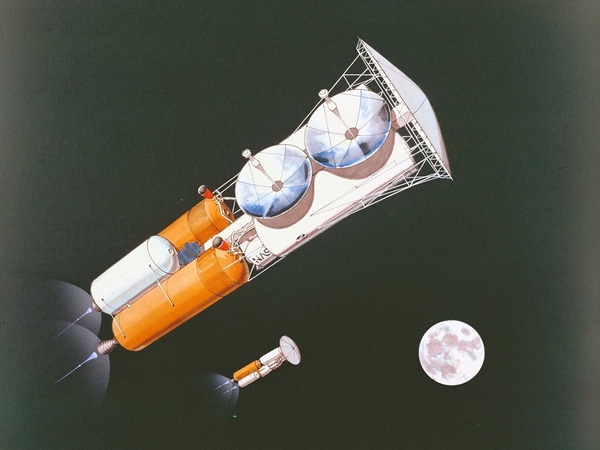

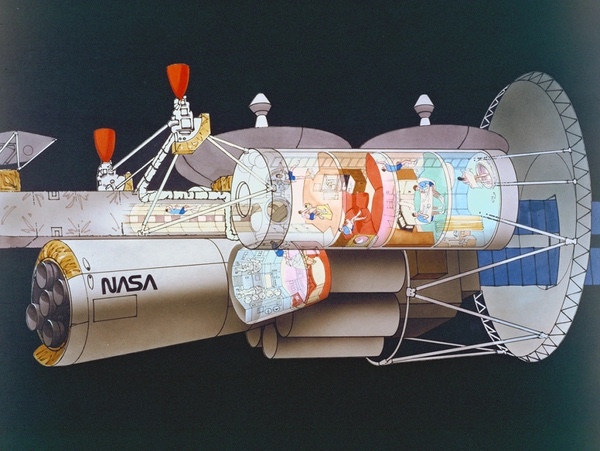

Each vehicle would have two habitat modules and a Mars shuttle. (credit: Carter Emmart) |

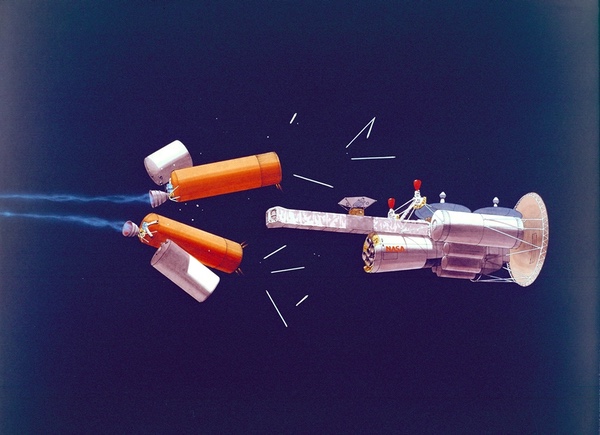

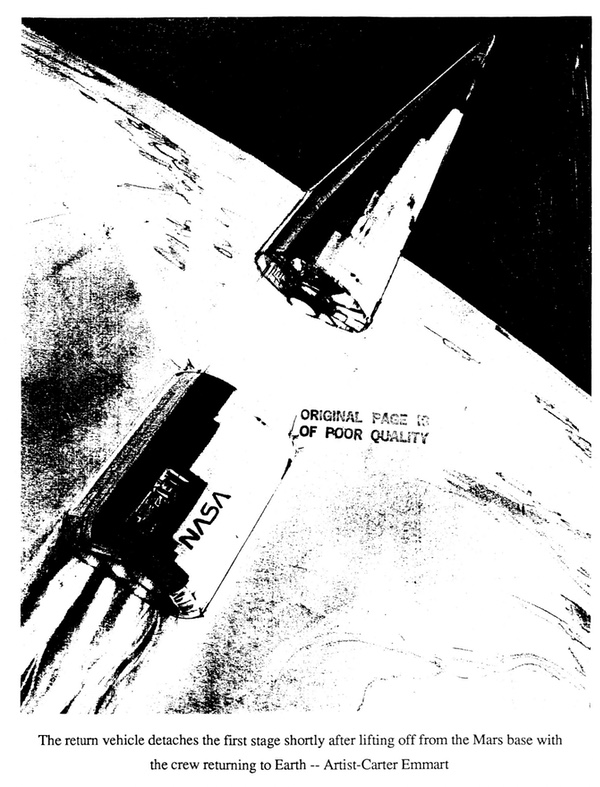

The Deep Space Habitat vehicles would travel on a Mars-powered flyby and return to Earth. The Deep Space Habitat vehicle would perform a propulsive maneuver as it flew by the planet. It would do this without a crew onboard—the crew having departed in Mars Shuttles to descend to the surface. Shuttles departing Mars would rendezvous with the Habitat vehicle on the outbound leg departing Mars. Mars Shuttles on the base would be refueled using carbon monoxide/oxygen propellant manufactured from Martian carbon dioxide. The returning crews would again get into their Mars Shuttles as the Habitat was nearing Earth and then aerobrake down to the space station. The Habitats would also aerobrake into Earth orbit for resupply for another trip.

The first mission would leave Earth in 2007, returning in 2012, followed by additional crews in 2009 and 2011. The schedule would require at least two cycler spacecraft. Crews would be transferred to the cyclers in Crew Shuttle vehicles. Each mission would deliver 15 crew members to Mars. Early on, some missions would return a lower number, perhaps nine, to Earth, enabling the population to gradually build up.

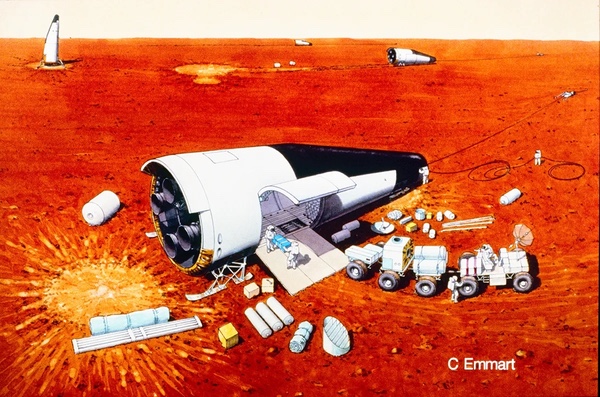

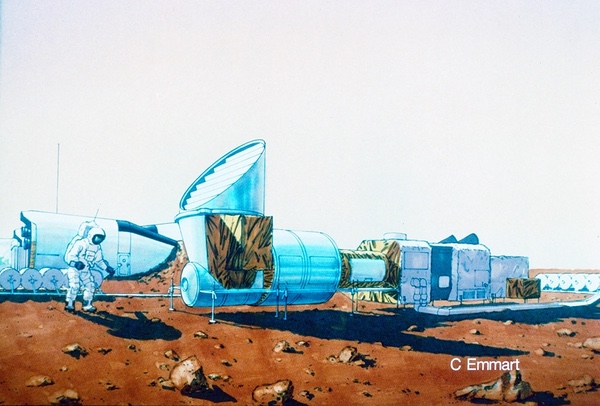

Crewed landers would be preceded to Mars by cargo landers. The plan was to establish a base that would be permanently crewed. (credit: Carter Emmart) |

The Mars Shuttles were described as biconic two-stage vehicles that would aerobrake at both Earth and Mars. There would be two-stage crew-carrying vehicles and one-way cargo-carrying vehicles.

The Deep Space Habitat would consist of three identical sections assembled at an Earth-orbiting space station. They would each have two space station modules, a life support system, consumables storage, a propulsion system, and power supply. The two modules would be mounted along a boom and tunnel that terminated in a docking adapter allowing the three sections to dock in a pinwheel configuration that would rotate to provide artificial gravity. A Mars shuttle would be docked along each boom. The sections would be boosted separately on a Mars-bound trajectory and would rendezvous and dock on the way to Mars. A Trans-Mars injection stage, equipped with adaptations of Space Shuttle Main Engines, would boost the Habitat/Mars Shuttle assemblies out of Earth orbit and into Mars transfer trajectory. The cargo versions of the Mars Shuttle would travel to Mars individually, not attached to a habitat.

One of the key aspects of the mission design was the use of Mars resources, including converting the thin atmosphere into fuel for the shuttles as well as for ground vehicles. (credit: Carter Emmart) |

Although the Space Shuttle would be used for some aspects of in-orbit assembly, the mission required a heavy-lift rocket capable of placing at least 75 metric tons in low Earth orbit. Twenty-four heavy-lift and 20 shuttle launches would be required to launch the first expedition.

The shuttles would return part of the crew to a cycler spacecraft bringing new crew and supplies. (credit: Carter Emmart) |

The Mars base would use in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) to create propellant from the thin atmosphere of Mars, a concept that had been studied starting in the 1970s. The report stated that “propellant production on the surface of Mars is critical to reducing the cost of the program” because it “reduces the Earth launch weight by almost an order of magnitude.” Each Crew Mars Shuttle would require 150 tons of Mars ISRU-manufactured carbon monoxide/oxygen propellant to catch up with the passing Earth-bound cycler. The Case for Mars II workshop proposed that an automated probe should test ISRU propellant production on Mars before the Mars base program began.

The report added that “Mars is abundantly endowed with all the resources necessary to sustain life.” The base would include greenhouses for food production. As a summary noted, “Development of long-duration life support is seriously lagging behind other technologies relevant to human missions to Mars.”

The Habitat vehicles would aerobrake at Earth for refurbishment and reuse for the next outbound mission. (credit: Carter Emmart) |

“The initial focus of activities at the Mars base must be the development of resource utilization technologies, since the continued presence of the base and the long-range science goals are contingent on establishing the resource base.” Additional subjects needing further attention included the power supply that could provide approximately 200 to 400 kilowatts, Mars spacesuit design, small engines that could run on fuel in-situ, and the study of life support and resource utilization.

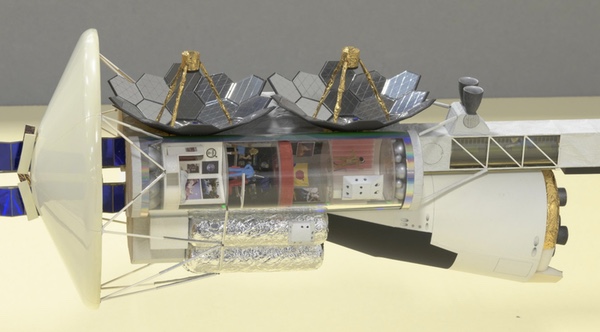

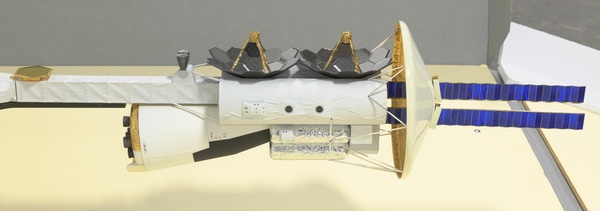

A model built by Carter Emmart was displayed in the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in the 1990s and again in 2014. It is not currently on display. (credit: Smithsonian Institution) |

Artwork and Cycler model

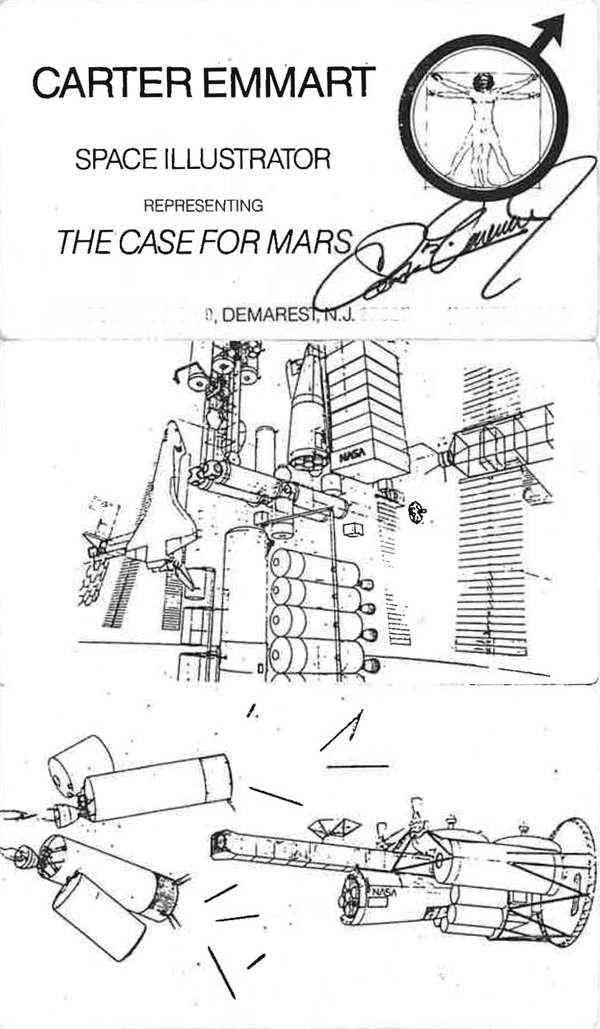

Carter Emmart was a student at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and an artist and illustrator. During the workshop, he developed sketches of the spacecraft and overall mission concept. Over the next several years he refined his artwork, making color pencil illustrations that later appeared (in black and white) in the summary proceedings of the Case for Mars III conference, which was held in summer 1987.

Emmart later built two complete models of the Mars Cycler spaceship, donating one to the Smithsonian. One of the habitat modules had a clear panel side, revealing the astronauts living and working inside, including the obligatory person taking a shower (something that had appeared in earlier cutaway depictions of space stations and was sort of an inside joke among space artists.) The model went on display in 1992 in the “Where Next, Columbus?” exhibit about the future of space exploration at the National Air and Space Museum in downtown Washington, DC. A decade later when the exhibit closed it was removed from display but went back on exhibit in a new gallery in 2014. It is not currently on display.

TCarter Emmart built two models of the Mars cycler spaceship, one of which he donated to the National Air and Space Museum. That model included a cutaway section showing the living spaces. (credit: Smithsonian Institution) |

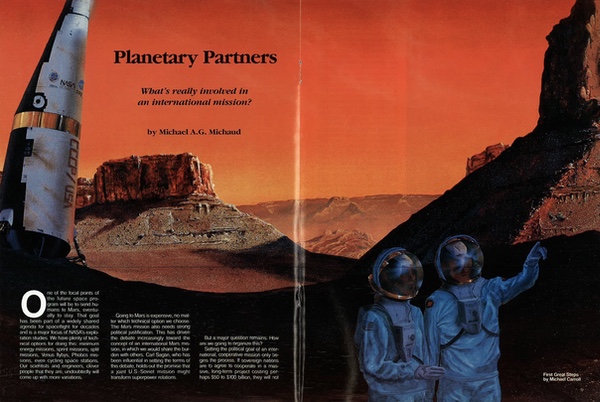

Michael Carroll, another artist who was at the Case for Mars II conference, produced drawings and later color illustrations of aspects of the mission. They appeared in the proceedings and elsewhere. However, Emmart illustrated the mission’s various phases, and his artwork appeared in more publications.

Carter Emmart’s business card depicted the various phases of the Case for Mars human Mars mission concept. (credit: Carter Emmart) |

Legacy

There have arguably been five general cultural phases of human Mars exploration concepts—“cultural” because they influenced the public discussion of human Mars exploration. The first was the 1950s Collier’s magazine spaceflight series, which included a mission to Mars illustrated by famed illustrator Chesley Bonestell, later followed by a 1950s Disney animated Mars mission. Bonestell’s version featured a large winged Mars lander. The Disney film depicted an umbrella-shaped Mars transfer spacecraft that rotated for artificial gravity.

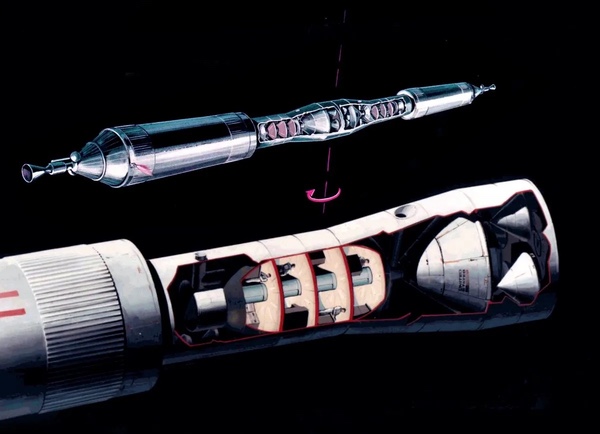

Before the Case for Mars mission concept, during the 1970s and 1980s the most common depiction of a human mission to Mars was based upon a 1969 mission design produced by NASA. (credit: NASA) |

The second phase was the 1970s era of the Integrated Mars Plan that had been developed in 1969 and featured large nuclear-propelled spacecraft flying to Mars. During the 1970s into the 1980s, artwork of the Mars spacecraft from the Mars Integrated Plan appeared in various non-fiction books, and the mission concept appeared in several novels (The Throne of Saturn and The Far Call, and Stephen Baxter’s Voyage). For people interested in future human Mars exploration during this time, it was a concept that they were most familiar with (see “Flights to Mars, real and LEGO,” The Space Review, July 6, 2021.)

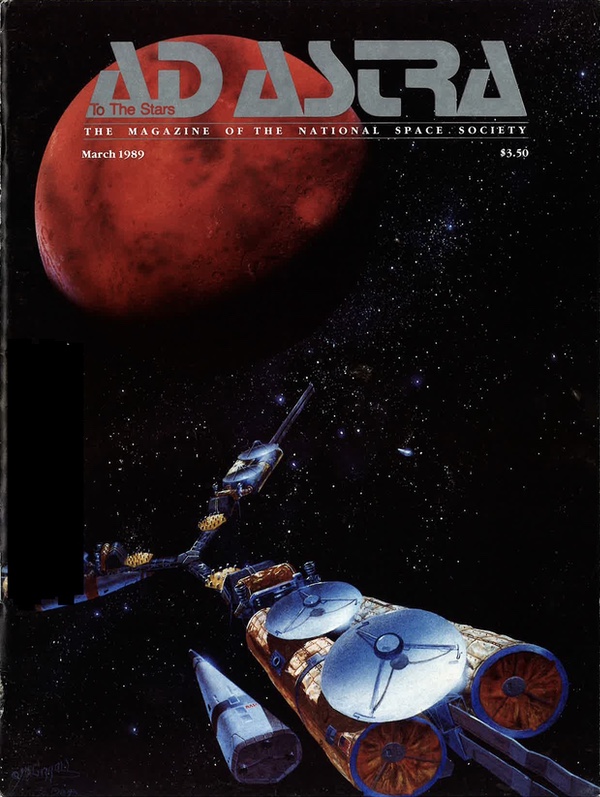

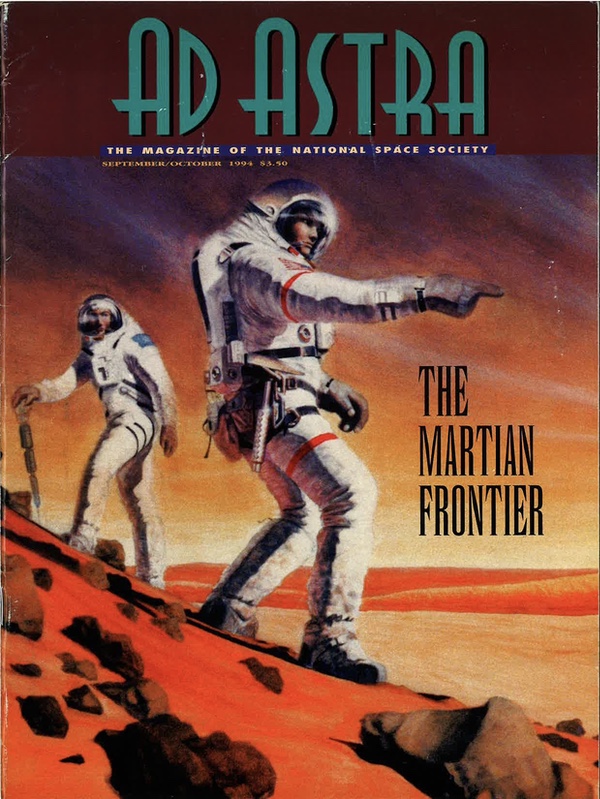

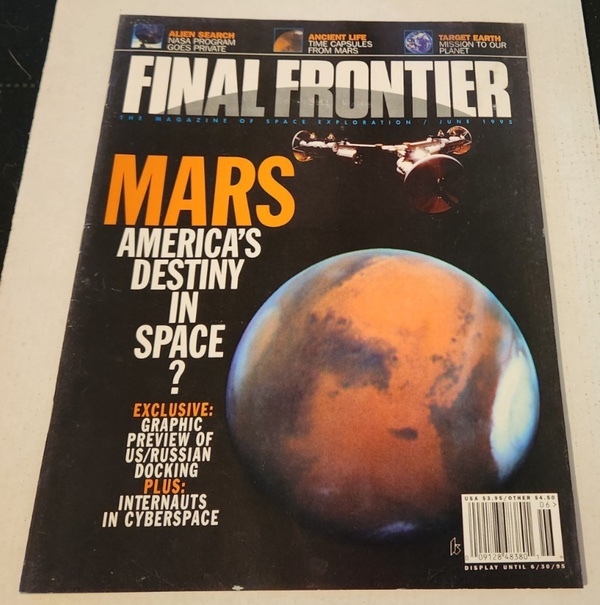

The third phase was the 1980s era of the Case for Mars cycler plan. After the Case for Mars II conference, Carter Emmart’s artwork appeared in numerous publications, and the cover of a magazine. Michael Carroll’s artwork also appeared on the cover of a magazine and other publications. The mission concept also appeared in Allen Steele’s 1992 book Labyrinth of Night and Ian Douglas’ Semper Mars. These examples demonstrated the powerful value of having artwork to illustrate a concept such as a mission to Mars. There were admittedly other Mars mission concepts during this era, some of which appeared on the covers of books and magazines, but none were as wide-reaching as the Case for Mars concept.

Robert Zubrin later developed a different concept for human Mars exploration called “Mars Direct.” A primary aspect of Mars Direct was sending an unpiloted spacecraft to land at Mars to produce fuel before sending a human mission to land nearby, using the refueled spacecraft for return to Earth. Zubrin’s concept, like the earlier Case for Mars concept, used in-situ resources for rocket propellant. Zubrin later wrote a book called The Case for Mars, using the name of the conference, and was also the subject of a documentary called The Mars Underground, but although he appropriated the terms, he is not listed as one of the original workshop participants. Zubrin’s “Mars Direct” concept endured throughout much of the 1990s and influenced several movies, including 1998’s Mission to Mars (Zubrin was a technical consultant).

The Case for Mars workshop did not invent the concept of in situ resource utilization at Mars for propellant and oxygen, but certainly gave it greater visibility. The workshop also established the concept of a continuous presence on Mars rather than a single “flags and footprints” approach. Both that concept and Zubrin’s “Mars Direct” had greater public exposure than several NASA Design Reference Missions produced in the 1990s and 2000s. Today, the primary cultural influence on how the public perceives Mars missions comes from the SpaceX Starship program, although its incredible ambition—500 launches to Mars in 2033 and a million people living there within a decade—also makes it seem a bit fanciful.

Many of the Case for Mars participants later went on to have prominent careers in the planetary science field. As one example, Penny Boston later headed NASA’s Astrobiology Institute. Carter Emmart, an exuberant, enthusiastic, eccentric space advocate, spent several decades working at the American Museum of Natural History where he created planetarium shows seen by millions of visitors.

Artwork by Carter Emmart and Michael Carroll appeared in publications after the conference and helped communicate the proposal and gain more public notice. The Case for Mars II Mars mission concept even appeared in novels in the early 1990s. (credit: Carter Emmart and Michael Carroll) |

Notes

Univelt published the proceedings for the Case for Mars conferences, an invaluable resource on this topic for over a decade.

J.R. French, “The ‘Case for Mars’ Concept,” Jet Propulsion Laboratory, 1987.

The Case for Mars II: proceedings of the Second Case for Mars Conference held July 10-14, 1984, at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Alcestis Oberg, “The Grass Roots of the Mars Conference,” AAS 81-225, Penelope Boston, editor, The Case for Mars (San Diego, CA: Univelt, Inc., 1984), p. ix.

S. M.Welch and C. R. Stoker, editors, The Case for Mars: Concept Development for a Mars Research Station (Boulder, CO: Boulder Center for Science Policy, 10 April 1986).

Thomas Paine, “A Timeline for Martian Pioneers,” AAS 84-150, Christopher McKay, editor, The Case for Mars II (Univelt, Inc., 1985), pp. 18-19.

Michael Duke, Wendell Mendell, and Barney Roberts, “Lunar Base: A Stepping Stone to Mars,” AAS 84-162, Christopher McKay, editor, The Case for Mars II (Univelt, Inc., 1985), pp. 207-20.

Humboldt Mandell, “Space Station—The First Step,” AAS 84-160, Christopher McKay, editor, The Case for Mars II (Univelt, Inc.,1985), pp. 157-70.

David S.F. Portree, Humans to Mars Fifty Years of Mission Planning, 1950–2000, NASA History Division, NASA Headquarters, Washington, DC 20546, Monographs in Aerospace History Series, Number 21, February 2001

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.